By J J O’Connor and E F Robertson, from MacTutorHistory Website

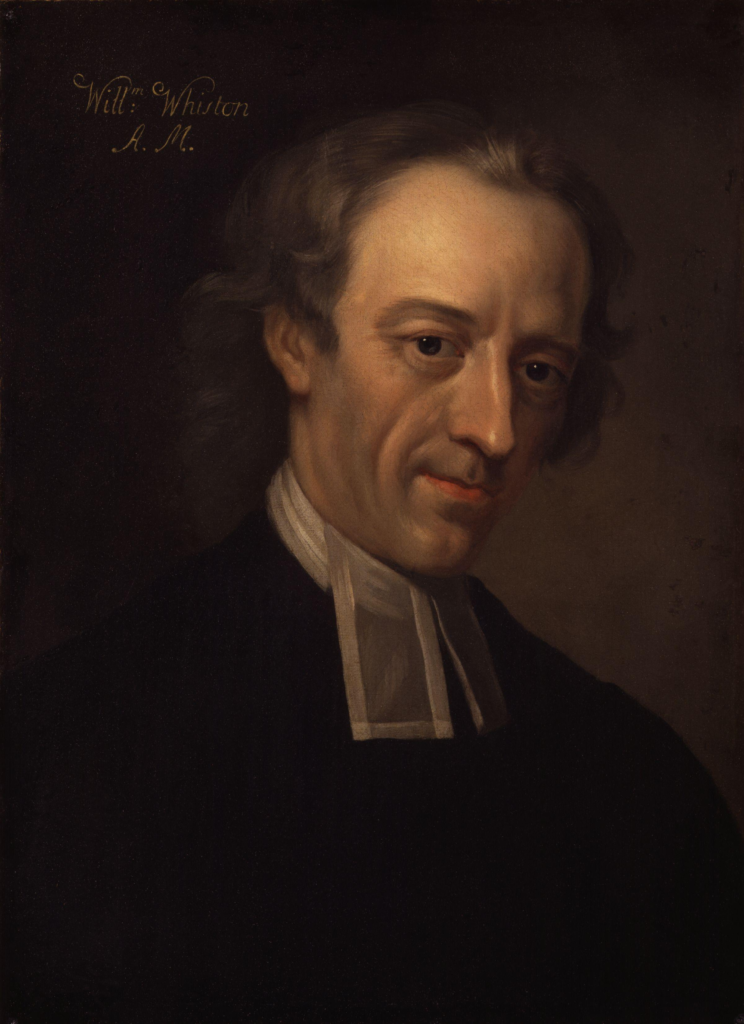

William Whiston

William Whiston (9 December 1667 in Norton, Leicestershire, England – 22 August 1752 in Lyndon Hall, Rutland, England) was an English theologian, historian, natural philosopher, and mathematician, a leading figure in the popularization of the ideas of Isaac Newton. He is now probably best known for helping to instigate the Longitude Act in 1714 (and his attempts to win the rewards that it promised) and his important translations of the Antiquities of the Jews and other works by Josephus (which are still in print). He was a prominent exponent of Arianism and wrote A New Theory of the Earth. Whiston succeeded his mentor Newton as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. In 1710 he lost the professorship and was expelled from the university as a result of his unorthodox religious views. Whiston rejected the notion of eternal torment in hellfire, which he viewed as absurd, cruel, and an insult to God. What especially pitted him against church authorities was his denial of the doctrine of the Trinity, which he believed had pagan origins.

William Whiston succeeded Newton as Lucasian professor at Cambridge, but was later deprived of his chair on religious grounds.

William Whiston’s father was Josiah Whiston who was a presbyterian minister at Norton. William’s mother was Katherine Rosse, whose father Gabriel Rosse had been the minister of Norton parish immediately prior to Josiah Whiston. William, the fourth of his parents nine children, was born in the rectory at Norton. William was taught by his father until he was 17, but he also acted in a secretarial role by copying manuscripts for his father. In 1684 he went to the grammar school in Tamworth then, in 1686, after two years of school, he entered Clare College, Cambridge. He was very poor since his father died shortly before he went to university. However Whiston inherited the family library and was following his father’s wishes that he train to become a presbyterian minister.

William attended Newton’s lectures while at Cambridge and he showed great promise in mathematics. He obtained his B.A. in 1690, then obtained a fellowship at Clare College in 1691. Two years later he was awarded an M.A. and was ordained in the same year. He was encouraged by David Gregory at this time to study Newton’s Principia. He returned to Cambridge, intending to take mathematics pupils, but ill health made him give up his position as a tutor at Clare College.

From 1694 to 1698 he was chaplain to the bishop of Norwich. During this period, he wrote A New Theory of the Earth (1696), in which he claimed that the biblical stories of the creation, flood etc. could be explained scientifically as descriptions of events with historical bases. He relied heavily on applying Newton’s physics (in fact the book was dedicated to Newton) and on the new ideas about geology which were then being developed, to support the biblical account. For example he claimed that the biblical flood was due to a comet hitting the Earth, an interesting theory given the current interest in theories of this type. Of course the work mixed science and religion to the extent that Whiston claimed that the comet was divinely guided. A New Theory of the Earth proved very popular with French and German translations appearing. Even those such as Buffon who criticized Whiston’s book accepted some his ideas which they incorporated into their own theories.

In 1698 Whiston obtained a vicarage in Suffolk at Lowestoft-with-Kissingland. Up to this time he had continued to hold his fellowship at Clare College, but he resigned in June 1699 which he was forced to do in order to marry. He married Ruth Antrobus who was the daughter of the headmaster of the grammar school in Tamworth which he had attended. They had eight children, of whom four (Sarah, William, George, and John) reached adulthood. His father-in-law, George Antrobus, gave the newly married couple a farm near Dullingham in Cambridgeshire which provided them with an annual income. He was appointed assistant to Newton at Cambridge from February 1701. However Whiston fell out with Newton over Bible chronology for, unlike Newton’s, his cosmology involved direct intervention by God. Despite this much of Whiston’s religious beliefs seem close to those of Newton.

In May 1702 Whiston succeeded Newton as Lucasian professor and, in the following year, he published an edition of Euclid for the use of students at Cambridge. With Newton’s agreement, Whiston published Newton’s algebra lectures in 1707 under the title Arithmetica universalis and, three years later, his own astronomy lectures as Praelectiones astronomicae. The English version was published in 1715 as Astronomical Lectures. He lectured at Cambridge on mathematics and natural philosophy and, after Roger Cotes was appointed to the Plumian professorship in 1706, receiving strong recommendations from Whiston, they undertook joint research. Together they introduced the first courses on experimental physics at Cambridge.

Whiston also published religious works such as Essay on the Revelation (1706). He came to believe that the doctrine of the Trinity was incorrect (as did Newton) and, although at first careful not to publicly oppose the views of the established church, he later became bolder and published his views in Sermons and Essays (1709). These views were not popular and, after he refused to acknowledge that he was in error, he was brought before the heads of the Cambridge colleges charged with heresy. He was deprived of his chair on 30 October 1710 and dismissed from Cambridge University. He went to London where a court was set up by the lord chancellor to try him for heresy but, after the death of Queen Anne, proceedings against him were dropped.

A German visitor to London who met him in 1710 described him as being:

… of very quick and ardent spirit, tall and spare, with a pointed chin and wears his own hair.

In looks, he greatly resembles Calvin.

He is very fond of speaking and argues with great vehemence.

Whiston was now rather poor and lived off the income of a small farm near Newmarket. To make money he formed a partnership with Francis Hauksbee, who was twenty years his junior, and from 1713 they gave a course covering mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics, and optics. In the following year they produced a course manual which was widely used and later formed the basis of some of the courses at Oxford. He lectured in the coffee-houses of London, being one of the first to demonstrate science experiments during the lectures. As time went on his financial position improved as various patrons provided an income for him. As a result, without needing to make money, he lectured less.

In 1714, along with Humphrey Ditton, Whiston approached parliament advising them to encourage work on solving the longitude problem by offering large financial rewards.

The idea was supported by:

- Newton

- Clarke

- Cotes

and Halley and the result was the Longitude Act passed by parliament later in 1714.

Having been one of the main enthusiasts for the Longitude Act, Whiston now proposed a number of methods of finding the longitude at sea; there was a lot of money for a good solution, but he never succeeded. The methods he proposed included having vessels stationed at fixed points across the Atlantic, having each fire a star shell at a fixed time each day. Ships would be able to calculate their distance from such a vessel by calculating the time taken for the sound of the shell to reach them after the flash was observed. One of his proposals concerned magnetic inclination and is certainly not without interest.

Howarth writes that Whiston:

… made the first known maps showing the direction of magnetic inclination (for south-eastern England) in 1719 and 1720.

He also anticipated Graham’s 1723 measurement of the ratio of horizontal and vertical magnetic intensities, and he understood their relationship to magnetic inclination.

Howarth then tries to understand how Whiston fitted the planar isoclinic surfaces:

This is of interest because his study precedes the publication of ’Meyer’s method’ by thirty-one years and the Legendre-Gauss ’method of least squares’ by eighty-six years.

It is suggested that Whiston fitted the surfaces using observations of inclination at a chosen triple of localities; and that he did this in order to use data from non-included localities as a check on his model.

Whiston published The Longitude and Latitude Found by the Inclinatory or Dipping Needle in 1721.

While he was being subjected to charges of heresy, he was bold enough to set out his religious beliefs in a series of pamphlets Primitive Christianity Revived (1711-12). Wanting to return to an early form of Christianity, he founded the Society for Promoting Primitive Christianity in 1715 which held meetings in Whiston’s London home. Continuing with his theme of science and religion, he published Astronomical Principles of Religion in 1717. He left the Church of England in 1747 because of his objection to the Athanasian creed, and joined the Baptists.

Lyndon Hall, where Whiston died, was the residence of Samuel Barker, the husband of Whiston’s daughter Sarah. Ruth Whiston died in 1751, and Whiston died in the following year after being ill for one week. He was buried in Lyndon churchyard.

SAUCE:

William Whiston (bibliotecapleyades.net)