Chapter 1: Introduction: The King James Bible – A Legacy of Controversy

A book by VCG via AI on 6/15/2025

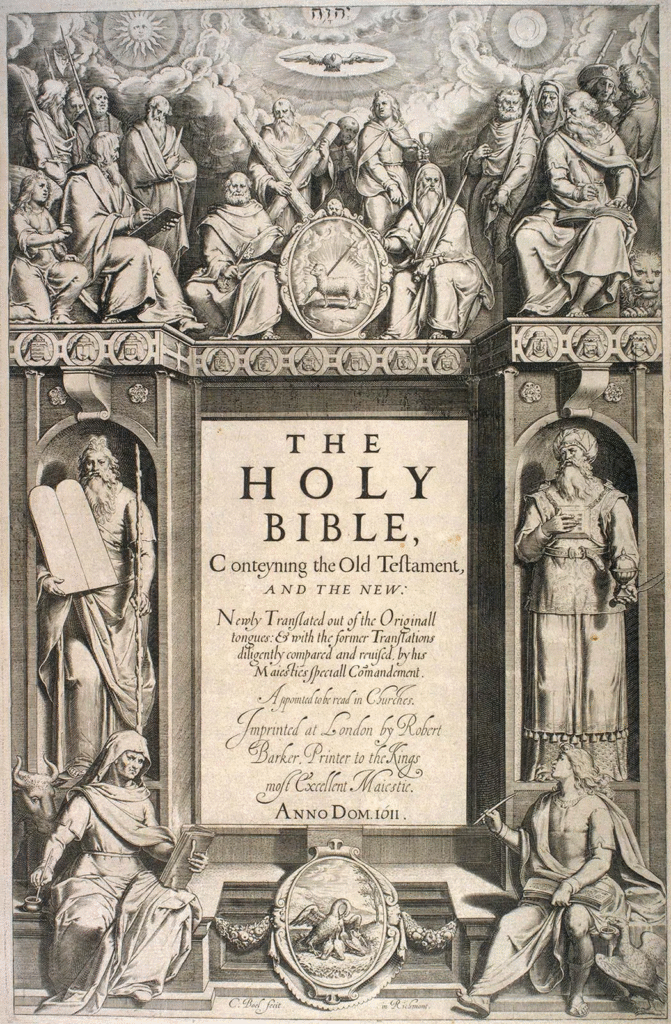

The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, completed in 1611, is far more than just a translation; it’s:

- a cultural touchstone

- a literary masterpiece

- a potent symbol of English identity

Miles Williams Mathis: The English Revolution – Library of Rickandria

Its influence reverberates through centuries, profoundly shaping English literature, language, and even the very fabric of Western society.

While modern translations strive for greater accuracy and clarity, the KJV retains an unparalleled hold on the popular imagination and continues to be widely read and cherished.

This enduring influence stems from a confluence of factors: its majestic prose, its historical significance, its association with a pivotal moment in English history, and even the mystique surrounding its creation and the individuals involved.

The KJV’s impact on the English language is undeniable.

Its rich, evocative language, characterized by its dramatic imagery and powerful rhythm, significantly enriched the vocabulary and literary style of the English tongue.

Many phrases and expressions from the KJV have become ingrained in everyday speech, so much so that their biblical origins are often overlooked.

Consider phrases like

“the powers that be,”

“a wolf in sheep’s clothing,”

“the salt of the earth,”

or

“an eye for an eye.”

These expressions, originally drawn from the KJV, have become so deeply woven into the linguistic fabric of English that they are virtually inseparable from the language itself.

This pervasive influence highlights the KJV’s profound and lasting impact on how English is spoken and written.

Its influence extends beyond mere phrases; its majestic sentence structures and poetic cadence have served as a model for countless writers throughout the centuries, shaping the very style of English prose and poetry.

Beyond its linguistic impact, the KJV holds a special place in English literature.

Its cadences and imagery have inspired countless works, from Milton’s Paradise Lost to the countless novels, poems, and plays that have drawn upon its language and imagery.

Paradise Lost – Anna’s Archive

The KJV’s influence is evident in the works of Shakespeare and other writers of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, as well as those who followed.

The KJV’s imagery and language influenced the development of English literature, shaping its literary style and contributing to the richness and diversity of English writing.

The KJV’s influence isn’t confined to the realm of high literature.

It permeates popular culture as well.

From film and television adaptations of biblical stories to musical references and countless allusions in everyday conversation, the KJV remains a constantly present force.

The iconic King James phrasing—often quoted even by those unfamiliar with the context—continues to shape the narratives and dialogues of contemporary entertainment, subtly shaping public perception and cultural understanding of biblical stories.

The emotional weight and literary beauty of the KJV contribute to a continued fascination, ensuring that even in modern contexts, its influence endures.

Moreover, the KJV’s ongoing use in religious ceremonies across various denominations underscores its enduring power.

Despite the availability of newer translations deemed more accurate, many churches and congregations continue to utilize the KJV for its liturgical familiarity and its emotionally resonant language.

The inherent authority and gravitas associated with the KJV’s age and tradition contribute significantly to its continued use in religious practice, creating a sense of continuity with the past and a feeling of profound connection to religious tradition.

The familiar sounds of the KJV passages, read and chanted through generations, maintain a strong hold on the spiritual experiences of millions, regardless of whether they fully understand the underlying text.

The enduring appeal of the KJV, despite its archaic language and acknowledged textual variations compared to other versions, speaks volumes about its cultural resonance. This is not simply a matter of tradition, but a testament to the text’s literary beauty, its historical weight, and its profound impact on the development of English language and culture. The KJV’s continued influence, transcending linguistic changes and religious debates, emphasizes the unique power of language and the enduring connection between a historical text and the cultural consciousness it shaped.

This continued presence isn’t simply due to inertia or nostalgia.

The KJV’s linguistic richness provides a unique depth of expression unavailable in later, more literal translations.

Its phrasing, often considered more poetic and evocative, often captures the nuances and emotional weight of the original texts more effectively, leading to a more powerful and memorable reading experience.

Modern translations may prioritize accuracy, but the KJV offers a profound, deeply rooted aesthetic experience.

The KJV’s impact on the development of English prose style is a critical aspect of its lasting influence.

Before the KJV, English prose lacked the sophistication and stylistic complexity found in the translation.

The translators intentionally sought to create a dignified, stately prose style capable of conveying the majesty and authority of the biblical texts.

This stylistic ambition resulted in a text that transcended the merely functional nature of translation, establishing a new standard for English prose.

Its influence is evident in the evolution of literary style, shaping the writing style and the literary sensibilities of writers for generations to come.

The careful selection of vocabulary and the deliberate construction of sentences shaped not just the language of the Bible but the language of England.

Furthermore, the perceived “cognitive enhancement” through reading the KJV is a subject of ongoing debate.

Some argue that the richness and complexity of its vocabulary expands the reader’s intellectual capacity, encouraging more thorough and analytical engagement with the text.

However, this assertion requires further empirical research, considering factors such as the reader’s pre-existing literacy level and their motivation for engaging with the text.

The claim itself, however, speaks to the perception of the KJV as a text that transcends mere comprehension and engages the reader intellectually and emotionally.

Finally, the numerous conspiracy theories surrounding the KJV’s creation and its alleged Masonic connections, while ultimately unsubstantiated, contribute to its enduring mystique and appeal.

FREEMASONRY: Brotherhood of the Obligated Names – Library of Rickandria

These theories, however far-fetched, add a layer of intrigue to the already rich history of the translation, fostering a sense of fascination and prompting further investigation.

The very existence of these theories speaks to the enduring fascination with the KJV, cementing its position as a text that sparks both scholarly study and popular speculation.

Even the controversies surrounding its creation only serve to heighten its allure and strengthen its hold on the collective cultural consciousness.

In conclusion, the enduring influence of the KJV is a multifaceted phenomenon.

Its linguistic richness, its literary beauty, its historical significance, and even the intrigue surrounding its creation have contributed to its sustained popularity and relevance.

The KJV is not just a translation of a religious text; it is a foundational work of English literature, a cornerstone of English identity, and a testament to the profound power of language to shape cultures and societies.

Its continued influence in religious ceremonies, in literature, and in popular culture speaks to its lasting legacy and to the enduring power of its words.

The King James Bible remains a living text, its voice echoing through the centuries, reminding us of the extraordinary power of language and the enduring impact of a single book.

King James I, the Stuart monarch who ascended the English throne in 1603, stands as a pivotal figure in the history of the King James Bible.

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until his death in 1625. Although he long tried to get both countries to adopt a closer political union, the kingdoms of Scotland and England remained sovereign states, with their own parliaments, judiciaries, and laws, ruled by James in personal union.

Understanding his character, his religious convictions, and the political landscape of his reign is crucial to comprehending the motivations behind the commissioning of this landmark translation.

James, a shrewd and often ruthless politician, was deeply interested in consolidating his power and establishing religious uniformity within his kingdom.

His reign, spanning from 1603 to 1625, was a period of significant religious tension, marked by lingering conflicts between:

- Catholics

- Puritans

- established Church of England

James’s personal religious beliefs were complex and multifaceted.

While he was undeniably a staunch Protestant, his theological views were more nuanced than those of many of his contemporaries.

He was a staunch believer in the divine right of kings, a concept which posited that monarchs derived their authority directly from God, thereby making them answerable only to God himself. This belief significantly influenced his approach to religious matters, shaping his attempts to impose a degree of religious conformity upon his diverse realm.

His own understanding of Protestantism was colored by his Scottish Presbyterian upbringing and later refined by the intricacies of the Anglican Church’s hierarchical structure.

His early exposure to Presbyterianism gave him a deep understanding and respect for a structured form of church government.

However, he ultimately embraced the episcopal structure of the Church of England, albeit with some modifications.

This willingness to blend theological perspectives and even compromise on certain points is key to understanding his approach to the Bible translation project.

He saw the need for a translation that could be used by all denominations within his realm, thus promoting a sense of religious unity and reducing potential sources of dissension.

The Bible, he recognized, held immense power to shape public opinion and could be an extremely powerful tool for social control.

Furthermore, the commissioning of a new translation could serve multiple purposes simultaneously.

A unified English translation could help to suppress subversive religious groups, particularly the increasingly vocal Puritans who looked upon the Geneva Bible – with its extensive marginal notes often interpreted as supporting Presbyterian forms of church governance – with favor.

By providing a meticulously crafted alternative, James aimed to curb their influence and consolidate support for the Anglican Church as the established faith of the kingdom.

This political dimension of the translation must not be overlooked; it was not solely a religious venture.

The political climate of the early 17th century was fraught with instability.

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a Catholic conspiracy aimed at assassinating James and the entire English Parliament, cast a long shadow over his reign.

The lingering threat of Catholic rebellion and the presence of a significant Catholic minority within England created a climate of fear and suspicion.

This heightened sense of insecurity further amplified James’s determination to establish religious conformity and quell any potential sources of dissent.

The new Bible translation was, in a sense, a weapon in his arsenal, aimed at creating a sense of national unity and religious orthodoxy.

Beyond the Gunpowder Plot, other challenges existed. Religious disputes and controversies within England itself posed considerable obstacles to governing.

The tension between the established Church of England and various dissenting Protestant groups, such as the Puritans, fueled widespread discontent.

These groups differed sharply on theological matters, creating a climate of intellectual and religious warfare that seriously threatened social cohesion.

James, a skilled diplomat with a preference for peace and order, understood that a single, authoritative version of the Bible could bring unity across religious divides.

However, this was a more ambitious goal than it initially may have seemed.

The various existing English translations of the Bible all held different theological implications and possessed inherent biases, which led to religious fracturing.

- The Great Bible (1539)

- the Geneva Bible (1560)

- the Bishops’ Bible (1568)

were all deeply embedded within the fabric of English religious life, each carrying its own:

- history

- interpretations

- theological leanings

Some translations favored certain theological viewpoints, creating ideological battlegrounds within the kingdom.

This meant that simply commissioning a new translation wasn’t a mere task of linguistic precision; it was a bold political maneuver.

The decision to embark on a new translation wasn’t a spontaneous one.

It was a deliberate and meticulously planned project, designed to serve not only religious but also political ends.

James strategically assembled a team of the most learned scholars in the realm, ensuring a wide range of perspectives were represented, while also ensuring a degree of control over the final product.

The scholars involved were drawn from various theological backgrounds, including university professors, church officials and others known for their linguistic capabilities.

This careful selection reflected James’s attempt to balance competing interests and to create a translation that would be acceptable to the broadest possible range of his subjects.

The process itself was long and complex, involving years of careful deliberation and rigorous revision, a clear signal of the king’s commitment to a final product that would be widely accepted across all segments of the population.

James’s involvement in the project transcended merely authorizing the translation.

He actively shaped its direction, influencing its theological nuances and directing the overall tone and style.

He possessed a keen interest in theology and viewed the Bible as a cornerstone of his political authority.

His aim was to produce a translation that reflected his own theological understanding and that would simultaneously promote religious unity and reinforce his own authority.

This involved careful scrutiny of the process, ensuring that potential pitfalls were avoided and the final product aligned precisely with his own beliefs and political goals.

The King James Bible, therefore, was not merely a linguistic endeavor; it was a product of its time, reflecting the religious and political anxieties of early 17th-century England.

King James I’s role in its creation was far more significant than that of a mere patron.

He was an active participant, shaping the theological landscape, navigating political pressures, and overseeing a project that would profoundly shape English:

- culture

- literature

- religious

life for centuries to come.

His vision, a unified and authoritative English Bible, had significant political ramifications, solidifying his power and helping to establish a more unified and cohesive nation under his rule.

His legacy extends beyond the realms of politics and theology; it’s etched into the very language and culture of English-speaking peoples, a testament to the enduring power of his vision and the lasting impact of the King James Bible.

The King James Bible remains, in essence, a reflection of King James I’s reign – a testament to his ambition, his political skill, and his enduring influence on the course of history.

The Bible, in this sense, is also a historical artifact, a document revealing much about the anxieties and motivations of its time, reflecting the intricacies of religious and political power during this crucial period of English history.

The monumental task of translating the Bible into English, culminating in the King James Version, was not undertaken lightly.

King James I, far from merely commissioning the work, meticulously selected the team of translators, carefully balancing their theological viewpoints and linguistic expertise to ensure a final product that would serve both religious and political objectives.

The selection process itself offers a fascinating glimpse into the intellectual and religious landscape of early 17th-century England.

The translators were not a homogenous group; instead, they represented a spectrum of theological perspectives within the Church of England.

This was a deliberate decision on James’s part.

He understood that a translation undertaken by only one theological faction could easily become a source of further conflict.

By choosing scholars from differing backgrounds, he hoped to create a version acceptable to a wider audience, fostering religious unity and mitigating the potential for dissent.

This inherently complex undertaking required scholars of immense skill and deep theological understanding.

The chosen scholars were drawn from various institutions and backgrounds.

Many were professors from prestigious universities like Oxford and Cambridge, renowned for their classical learning and expertise in:

- Hebrew

- Greek

- Latin

– the original languages of the Bible.

Their mastery of these languages was paramount to the accuracy and nuance of the translation.

This wasn’t simply a matter of finding individuals who could understand ancient languages; it required scholars who could comprehend the subtle nuances of meaning and interpret complex theological concepts across vastly different cultural contexts.

The very act of translation is an interpretation, not just a direct conversion of words.

Furthermore, the team included church officials who brought with them a deep understanding of theological debates and the existing controversies surrounding biblical interpretations.

Their experience in resolving theological disputes within the Church of England provided valuable insight into the sensitivities involved in creating a text that could potentially influence—and even shape—the theological understanding of an entire nation.

The selection criteria went beyond mere linguistic proficiency and theological understanding; it also considered the individual’s reputation and character.

King James I needed individuals who were not only highly skilled and knowledgeable but also dependable, trustworthy, and capable of working collaboratively within the team.

The translators were divided into six groups, each assigned a specific portion of the Bible.

This division of labor ensured a more manageable workload and allowed for a degree of specialization, with each group focusing on a particular section of scripture.

This approach, however, posed unique challenges.

Ensuring consistency in:

- style

- tone

- theological interpretation

across the six different groups was a demanding task, requiring a rigorous process of review and revision.

The final product was meant to be singular in its essence despite the collaborative efforts, representing a unified vision rather than a collection of distinct interpretations.

The translators’ methods reflected the prevailing scholarly practices of the time.

They primarily relied on the most authoritative existing manuscripts available, which mostly meant Greek and Hebrew texts.

They meticulously compared various readings to arrive at the most accurate translation, striving to balance textual accuracy with readability and stylistic consistency.

This was a painstaking process involving countless hours of careful scrutiny, debate, and cross-referencing.

They examined the nuances of individual words, weighing their meanings in their various contexts, and seeking consensus on the best possible rendering into English.

The task was further complicated by the inherent complexities of translation.

Words often do not have direct equivalents across languages, necessitating careful consideration of context and meaning.

Theological concepts, deeply embedded within the cultural context of the original languages, required insightful interpretation and adaptation to English idiom.

The translators’ efforts went far beyond simply replacing one word with another; it involved a deep understanding of both the source and target languages, as well as the religious and cultural context within which the text was written and received.

The work was, in essence, a profound act of interpretation, a careful weighing of linguistic nuances and theological implications.

The theological leanings of the translators undoubtedly shaped the final product.

While they strove for objectivity, their own interpretations and beliefs inevitably influenced their choices.

This is not to suggest that the translation was biased in a malicious or deceptive manner, rather that the inherent limitations of translation made complete objectivity an impossibility.

Even the most dedicated scholar brings their own perspective to the process.

The translators, in their decisions regarding word choice, phrasing, and interpretation of ambiguous passages, inevitably reflected their own understanding and experience.

The challenge of maintaining consistency was substantial.

The different groups, while working independently, needed to adhere to a common standard.

This required a significant amount of communication and collaborative effort, with regular reviews and revisions of the work.

They had to reconcile the differing interpretations and styles which arose from their individual approaches, ensuring that the final product possessed a unified style and tone throughout.

This coordination, done amid the constraints of the time, involved significant effort, and reflects not only the care invested in the work but also the significance of their task to the English-speaking world.

The controversy that has dogged the King James Bible since its inception, even in its initial release, illustrates this unavoidable element of interpretation.

Critics and proponents alike have found evidence to support their positions within the KJV’s wording and specific theological leanings.

It’s essential to recognize that the King James Bible was not a divinely inspired, unchanging text dropped from the heavens; it was the product of human scholarship and interpretation, reflecting the religious, linguistic, and cultural context of its time.

The process of translating the Bible was not only a linguistic and theological undertaking; it was also deeply political.

King James I carefully selected his team, not simply for their academic credentials but also for their theological views, hoping to create a translation that would be acceptable to the broader church, bolstering the authority of his position and promoting religious unity.

The political implications of the translation, however, extended beyond this.

The choice of words, the emphasis on specific interpretations, and even the deliberate exclusion of certain texts, all carried political weight, shaping the religious and political landscape of England for centuries.

The King James Bible was, and remains, a powerful artifact of its time, reflecting the complex interplay of politics, theology, and human interpretation.

Its enduring legacy speaks not just to its linguistic beauty and enduring influence, but also to the intricate process of its creation, a testament to the skill, dedication, and inevitable human bias of those who undertook the monumental task of bringing the Bible to the English people in a new and powerful form.

The year 1605 cast a long shadow over the nascent King James Bible project.

The Gunpowder Plot, a Catholic conspiracy to assassinate King James I and blow up the Houses of Parliament, sent shockwaves through the nation, profoundly impacting the political and religious landscape in which the translation was unfolding.

Robert Catesby (c. 1572 – 8 November 1605) was the leader of a group of English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Born in Warwickshire, Catesby was educated at Oxford University. His family were prominent recusant Catholics, and presumably to avoid swearing the Oath of Supremacy he left college before taking his degree. He married a Protestant in 1593 and fathered two children, one of whom survived birth and was baptised in a Protestant church. In 1601 he took part in the Essex Rebellion but was captured and fined, after which he sold his estate at Chastleton.

This audacious attempt to overthrow the king, orchestrated by Robert Catesby and Guy Fawkes, created a climate of fear and suspicion that undeniably influenced the trajectory of the Bible’s production.

Guy Fawkes (/fɔːks/; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated in York; his father died when Fawkes was eight years old, after which his mother married a recusant Catholic.

The plot’s discovery, just days before the planned act of terror, was a stroke of immense fortune for King James.

Had the plot succeeded, the consequences would have been catastrophic, not only for the king and the government but also for the entire nation.

The ensuing chaos would have almost certainly jeopardized the ongoing translation project, perhaps indefinitely halting its progress.

The sheer scale of the planned destruction, aiming to decimate the political elite of England, highlighted the deep-seated religious and political tensions of the era.

The plot was not merely an isolated incident; it was a stark reminder of the precariousness of the king’s position and the deep divisions within English society.

The Catholic conspirators, driven by a fervent desire to restore Catholicism in England, viewed King James—a Protestant—as a usurper.

Their plan represented a desperate, albeit extremely violent, attempt to redress what they perceived as a profound injustice.

King James, having inherited a nation grappling with religious turmoil, had implemented policies aimed at solidifying Protestant dominance.

While he adhered to a relatively moderate Protestant stance, attempting to find common ground with Catholics, his policies were ultimately deemed insufficient by the plot’s conspirators.

This failure to appease a faction with significant political influence illustrates the fragility of religious peace in early 17th-century England and underscores the potential risks that the King James Bible project faced.

The immediate aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot saw a dramatic tightening of security measures across the realm.

The threat to the king’s life was very real, and the authorities implemented sweeping changes to ensure his safety and to prevent future attempts on his life.

These heightened security measures undoubtedly extended to the King James Bible project.

While specific details surrounding the security protocols implemented to protect the translators and their work remain scarce, it is reasonable to surmise that significant measures were taken to guarantee the safety of the project and its participants.

The translators, many of whom held prominent positions within the Church of England, could have easily become targets in the heightened atmosphere of fear and uncertainty following the foiled assassination attempt.

The political climate, already tense due to the ongoing struggle between Protestants and Catholics, was further aggravated by the Gunpowder Plot.

The plot served as a stark reminder of the potential for violence and chaos inherent in religious extremism.

This heightened state of anxiety might have subtly affected the translators’ work, influencing their interpretation of certain passages and possibly shaping the overall tone of the translation.

The context of fear and uncertainty could have led to a greater emphasis on passages relating to loyalty to the crown, obedience to authority, and the condemnation of rebellion.

The plot’s implications extended beyond mere security concerns.

The king’s near escape could have strengthened his resolve to create a unified, politically expedient translation of the Bible that reinforced his authority and solidified the national identity.

This could have subtly influenced the translators’ choices, either consciously or unconsciously, leading to a translation that aligned with the king’s political objectives.

In this regard, the Bible itself, far from being a purely religious artifact, became a tool of state, bolstering the authority of the crown and promoting a sense of national unity amid the backdrop of religious and political divisions.

It is plausible to argue that the Gunpowder Plot subtly, yet significantly, shaped the final product.

The context of fear, political instability, and near-catastrophe created by the plot may have influenced the translators’ choices of words, emphasis on specific theological points, and the overall presentation of the scripture.

The translators were working under extraordinary circumstances, an environment significantly changed by the near-successful assassination of their patron and the king.

Bloodlines of Kings – Library of Rickandria

Beyond the direct security concerns, the Gunpowder Plot undoubtedly impacted the public perception of the Bible translation.

The plot’s exposure showcased the deep-seated divisions within the nation, and the need for a unified, unifying force.

The Bible, being translated under the king’s direct commission and with such apparent care, could have been seen, both officially and unofficially, as a beacon of unity in a time of crisis.

The translation process, far from being a purely academic endeavor, became a vital symbol of stability and national identity.

The successful completion of the translation could have been seen as a symbolic victory over the forces of division and chaos represented by the Gunpowder Plot.

This narrative, however, should be approached with caution.

It is difficult to directly and definitively link specific changes or interpretations in the KJV to the Gunpowder Plot.

The available evidence is circumstantial, and the influence, if any, was likely subtle and indirect.

However, to ignore the historical context in which the KJV was created would be a grave oversight.

The Gunpowder Plot represents a pivotal moment in English history, and its impact reverberated far beyond the immediate aftermath.

Furthermore, the conspiracy theories surrounding the King James Bible, often linked to Freemasonry and esoteric knowledge, frequently utilize the Gunpowder Plot as a touchstone to support their claims.

FREEMASONRY: Brotherhood of the Obligated Names – Library of Rickandria

Some theorists posit connections between the plot, the translators, and even King James himself, suggesting that the Bible was subtly altered or encoded to reveal hidden meanings only accessible to a select few.

While these claims often lack credible evidence, exploring them within the context of the historical narratives offers valuable insight into the diverse interpretations of the KJV’s creation and its enduring legacy.

The Gunpowder Plot, though seemingly a distant historical event, provides a critical lens through which to examine the King James Bible’s creation.

It illuminates the political and religious context in which the translation was undertaken, highlighting the profound risks and the high stakes involved.

While definitive proof of a direct causal link between the plot and the final product remains elusive, the historical context indisputably played a role in shaping the overall project, its perceived purpose, and its eventual reception.

The shadow of the Gunpowder Plot lingers over the legacy of the King James Bible, serving as a constant reminder of the turbulent times in which it was born and the profound influence of historical context on even the most monumental of scholarly endeavors.

The enduring success of the KJV may, in part, owe its success to its ability to emerge as a symbol of unity and stability amidst a period of immense national upheaval, a silent testament to the resilience of both the nation and the project itself.

The Gunpowder Plot reminds us that even the most seemingly purely religious projects are deeply embedded in their socio-political contexts, a lesson crucial to understanding the true nature of the KJV’s enduring legacy.

The publication of the King James Bible in 1611 did not herald a unanimous chorus of praise.

While it eventually achieved a status bordering on iconic, its initial reception was far more nuanced and complex, reflecting the diverse religious landscape and political climate of early 17th-century England.

The immediate response wasn’t a single, unified voice but rather a tapestry of opinions woven from the threads of various religious factions, scholarly circles, and social classes.

The established Church of England, naturally, largely welcomed the KJV.

Its creation under royal commission, after all, positioned it as an official text, sanctioned by the highest authority in the land.

The translation’s elegance of language and perceived theological accuracy reinforced its acceptance within the Church hierarchy.

However, even within the Church’s ranks, dissenting voices could be heard.

Some clergy, particularly those with a strong attachment to earlier translations like the Geneva Bible, expressed reservations about specific textual choices or stylistic preferences.

The transition to a new, authoritative version, even one commissioned by the crown, wasn’t entirely frictionless; it entailed a readjustment of established practices and loyalties.

The subtle shifts in theological emphasis, although perhaps not immediately apparent to all, would gradually spark debate and discussion in the years to come.

The Puritan movement, a more reformist branch of Protestantism, exhibited a more ambivalent response.

Reformed Christianity – Wikipedia

While appreciating the literary qualities of the KJV, certain Puritans felt that its adherence to the Bishops’ Bible, which held less appeal to their theological leanings, compromised its accuracy and faithfulness to the original Hebrew and Greek texts.

The Geneva Bible, favored by many Puritans for its extensive annotations and often considered to hold a stronger Calvinist theological slant, remained a preferred choice for numerous congregations.

Miles Williams Mathis: John Calvin – Library of Rickandria

The KJV, despite its official status, did not immediately replace the Geneva Bible in the hearts and minds of many devout Puritans.

This difference highlighted the significant theological fault lines within Protestantism itself, divisions that extended well beyond the mere choice of a particular Bible translation.

Catholics, unsurprisingly, largely rejected the KJV.

The Bible’s translation directly reflected and reinforced the Protestant rejection of papal authority, and their opposition to the KJV was rooted in their fundamental disagreement with the Protestant faith itself.

They viewed the KJV as part of a broader Protestant agenda to undermine the Catholic Church’s influence and authority in England.

Catholics continued to rely on their own established Latin Vulgate and translations, maintaining a distinct and separate approach to scripture that directly opposed the views enshrined within the King James Version.

The KJV’s acceptance was a far cry from being universal.

Outside the established religious groups, the reaction among the general population was mixed.

The KJV’s impact on the literate classes, specifically the educated elite, was significant and immediate.

Its elegant prose and flowing rhythm quickly made it a favored text for reading and study.

Its immediate effect on literacy among the common people was far less profound; the high cost of printed Bibles restricted access.

The vast majority of the population remained illiterate and relied on sermons and oral traditions for their religious instruction.

Yet, the King James Version’s elevated language, its rich literary style, undoubtedly impacted the development of English literature and shaped the very fabric of the language itself.

Its influence on language was subtle and long-term rather than sudden and sweeping.

The initial critiques of the KJV varied considerably.

Some objections focused on specific textual variations compared to earlier versions, highlighting instances where the translators’ choices diverged from the preferences of certain religious groups or scholars.

The meticulous work of comparing the KJV against previous English versions, along with the original Greek and Hebrew texts, gave rise to a whole body of scholarly commentary.

These critiques were not always simple disagreements over semantics but represented deep-seated theological differences with wider implications for religious practice and doctrine.

Other critiques centered on perceived biases in the translation, accusations that the translators had subtly skewed meanings to favor specific theological interpretations or political agendas.

These criticisms often stemmed from suspicions that the translators had leaned towards a more High Church Anglican interpretation.

The subtleties of translation, with their potential to affect the nuances of meaning, were not lost on some of the more astute observers and critics.

Each choice of wording and phrasing, each grammatical structure employed, held potential for subtle shifts in meaning and interpretation.

The impact of the KJV extended far beyond the realm of strictly religious discourse.

The translation’s beautiful prose and powerful imagery found its way into literature, poetry, and even legal documents.

The KJV’s influence on the English language remains undeniable, enriching the vocabulary and shaping the stylistic evolution of English expression.

The pervasive use of its language in subsequent generations permeated the cultural consciousness, becoming intertwined with the very essence of English identity and national pride.

The early debates about the KJV are not merely historical curiosities.

They reveal a fascinating interplay between theological positions, political maneuvering, and the evolving dynamics of language and literature.

The controversies surrounding the translation reflect the deep religious and social divisions of the era, and the enduring popularity of the KJV can be seen as a testament to its literary merit and its deep-rooted influence on both religious faith and English culture.

Moreover, it highlights the complexities of translating sacred text and the inevitable impact of historical and cultural factors on even seemingly straightforward translational projects.

The KJV was not simply a new translation; it was a powerful cultural artifact that immediately affected the political, religious, and literary spheres of early modern England.

Its lasting influence continues to be debated and interpreted even now, centuries after its initial publication.

Examining the early reactions to the KJV also allows us to assess the broader impact of the translation on literacy and education.

The availability of a standardized and readily accessible English Bible, despite its cost, undoubtedly contributed to a growing literacy rate among some segments of society.

The use of the KJV in schools and churches facilitated the spread of literacy, as individuals were encouraged to read and engage with the sacred text.

This effect, however, was not uniform across the population, and the spread of literacy remained heavily influenced by class distinctions.

The ability to read and understand the KJV remained a privilege primarily accessible to the more educated classes for many years.

Furthermore, the linguistic richness of the KJV directly impacted the subsequent development of English literature.

Its distinctive style and language served as a model for countless writers, shaping the contours of English prose and poetry.

Its influence can still be detected today in the works of numerous authors, highlighting the profound and ongoing legacy of the KJV.

The KJV’s impact is inextricably tied to its language, style, and cultural influence rather than solely on its religious impact, illustrating the interconnectedness of language, faith, and culture.

In conclusion, the initial reception of the King James Bible was not simply a matter of unanimous approval.

It ignited debates and discussions that illuminated the pre-existing religious divisions within English society and beyond.

The contrasting perspectives of various religious factions, from the established Church of England to the Puritans and Catholics, reveal the complexities of interpreting and translating sacred texts, and underscores how cultural and political context deeply shaped the reception of such a monumental work.

The KJV’s legacy is not just its theological influence; it’s a tapestry woven from controversies, debates, and a continuing cultural impact that still resonates strongly today.

The early reactions highlight the intricate intersection of:

- faith

- politics

- language

proving that even seemingly objective projects like Bible translation are indelibly marked by the times and contexts of their creation.

The story of the KJV’s initial reception is a rich and complex narrative, a vital chapter in understanding the Bible’s enduring influence.

CONTINUE

Chapter 2: Textual Comparisons and Theological Implications – Library of Rickandria

King James Bible: Authorized by God? – Library of Rickandria

Chapter 1: Introduction: The King James Bible – A Legacy of Controversy

Chapter 1: Introduction: The King James Bible – A Legacy of Controversy – Library of Rickandria