MEDIA: TECH: INTERNET: History of ARPANET – Behind the Net

by Michael Hauben on 19 December 1994 from ISEP Website

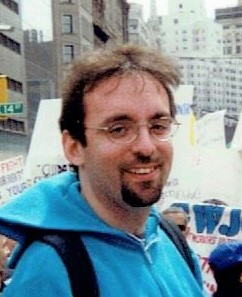

Michael Frederick Hauben (May 1, 1973 – June 27, 2001) was an American Internet theorist and author. He pioneered the study of the social impact of the Internet. Based on his interactive online research, in 1993 he coined the term and developed the concept of Netizen to describe an Internet user who actively contributes towards the development of the Net and acts as a citizen of the Net and of the world. Along with Ronda Hauben, he co-authored the 1997 book Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet. Hauben’s work is widely referenced in many scholarly articles and publications about the social impact of the Internet.

The untold history of the ARPANET

Or…

The “Open” History of the ARPANET/Internet

Introduction

The global Internet’s progenitor was the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) of the U.S. Department of Defense.

This is an important fact to remember, because the support and style of management by ARPA was crucial to the success of ARPANET.

As the Internet develops and the struggle over the role the Internet plays unfold, it will be important to remember how the network developed and the culture that it was connected with. (As a facilitator of communication, the culture of the Net is an important feature to acknowledge.)

The ARPANET Completion Report, as published jointly by BBN (Bolt, Beranek and Newman) of Cambridge, Mass., and ARPA concludes by stating:

“…it is somewhat fitting to end on the note that the ARPANET program has had a strong and direct feedback into the support and strength of computer science, from which the network itself sprung.” (Chapter III, pg.132, Section 2.3.4)

In order to understand the wonder that the Internet, and various parts of the Net, represent, we need to understand why the ARPANET Completion report ends with the suggestion that the ARPANET is fundamentally connected to and born of computer science.

Part I – The history of ARPA leading up to the ARPANET

A climate of pure research surrounded the entire history of the ARPANET.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency was formed with an emphasis towards research, and thus was not oriented only to a military product.

The formation of this agency was part of the U.S. reaction to the then Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957. (ARPA draft, III-6).

ARPA was assigned to research how to utilize their investment in computers via Command and Control Research (CCR).

Dr. J.C.R. Licklider was chosen to head this effort. Licklider came to ARPA from BBN in Cambridge, MA in October 1962. (ARPA draft, III-6)

From Licklider’s arrival, the department’s contracts were shifted from independent corporations towards,

“The best academic computer centers”. (ARPA draft, III-7)

The then current computing mode was via batch processing (you know, input via stacks of punched cards, output: results, or lack of them, made known one or more days later.).

Licklider saw improvements could be made in CCR only via work on advancing the current state of computing technology.

He particularly wanted to move forward into the age of interactive computing, and the current contractors were not moving in that direction.

In an Interview, Licklider told the interviewee that SDC,

“Was based on batch processing, and while I was interested in a new way of doing things, they [SDC] were studying how to make improvements in the ways things were done already.” (An Interview with J.C.R. Licklider conducted by William Aspray and Arthur Norberg on October 28, 1988, Cambridge, Mass. CBI Univ of Minn., Madison)

The office,

“Developed into a far-reaching basic research program in advanced technology.” (ARPA draft III-7)

Licklider’s Office was renamed Information Processing Techniques (IPT or IPTO) to reflect that change.

The Completion report states that,

“Prophetically, Licklider nicknamed the group of computer specialists he gathered the ‘Intergalactic Network’.” (ARPA draft, III-7)

Before work on the ARPANET began, the very idea of the network was planted by the creation of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) of ARPA.

Robert Taylor, Licklider’s successor at the IPTO, remembers Lick’s interest in interconnecting communities:

“Lick was among the first to perceive the spirit of community created among the users of the first time-sharing systems…

In pointing out the community phenomena created, in part, by the sharing of resources in one timesharing system, Lick made it easy to think about interconnecting the communities, the interconnection of interactive, on-line communities of people…” (ARPA draft, III-21)

The “spirit of community” was related to Lick’s interest in having computers help people communicate with other people (Licklider, Licklider, and Robert Taylor, “The Computer as a Communication Device”)

Licklider’s vision of an “intergalactic network” connecting people represented an important conceptional shift in computer science.

This vision was also an important beginning to the ARPANET.

After the ARPANET was up and running, the computer scientists using it realized that assisting human communication was the most fundamental advance that the ARPANET made possible. (Cite Larry Roberts)

As early as 1963, a common question asked of the IPTO directors by the ARPA directors about IPTO projects was

“Why don’t we rely on the computer industry to do that?”

or occasionally more strongly,

“We should not support that effort because ABC (read, “computer industry”) will do it – if it’s worth doing!” (ARPA draft, III-23)

This question leads to an important point – this ARPA research was different from what the computer industry had in mind to do – or was likely to undertake.

Since Licklider’s creation of the IPTO, the work supported by ARPA/IPTO continued his explicit emphasis on communications.

The Completion Report explains,

“The ARPA theme is that the promise offered by the computer as a communication medium between people, dwarfs into relative insignificance the historical beginnings of the computer as an arithmetic engine.” (ARPA draft, III-24)

The Completion Report goes on to differentiate ARPA from the computer industry:

“The computer industry, in the main, still thinks of the computer as an arithmetic engine.

Their heritage is reflected even in current designs of their communication systems.’

They have an economic and psychological commitment to the arithmetic engine model, and it can die only slowly…” (ARPA draft, III-24)

The Completion Report further analyzes this problem by tracing it back to the nation’s institutions:

“…furthermore, it is a view that is still reinforced by most of the nation’s computer science programs.

Even universities, or at least parts of them, are held in the grasp of the arithmetic engine concept…” (ARPA draft, III-24)

Since Licklider’s creation of the IPTO, the work supported by ARPA/IPTO continued the explicit communications emphasis.

Thus, history has witnessed the research and development which had led to the concrete existence of first the ARPANET, and later the Internet.

SoSHHial Media: The Jewish Hand Behind the Internet – Library of Rickandria

Without the commitment that existed via this support, such a development might never have happened.

One of ARPA’s criterion for supporting research was such that it had to be of such a level to offer an order of magnitude of development.

As most research and development is not immediately profitable, there has to be some kind of organization which helps to set higher goals than just in developing what will be immediately profitable.

What is really strange is that computer networking is an immensely profitable field right now – only it is 25 years later.

Others have understood the communications promise of computers.

For example, in RFC 1336, David Clark is quoted,

“It is not proper to think of networks as connecting computers.

Rather, they connect people using computers to mediate. The great success of the internet is not technical, but in human impact.Electronic mail may not be a wonderful advance in Computer Science, but it is a whole new way for people to communicate.

The continued growth of the Internet is a technical challenge to all of us, but we must never lose sight of where we came from, the great change we have worked on the larger computer community, and the great potential we have for future change.”

Various research outside of ARPA had been done by Paul Baron, Thomas Marill and others.

[This history is covered well in the article “From ARPANET to USENET” by Ronda Hauben.]

This led Lawrence Roberts and other IPTO staff to formally introduce the topic of networking computers of differing types (incompatible hardware and software) together in order to share resources to the early 1967 meeting of ARPA’s Primary Investigators (PI).

In the spring of 1967 at the University of Michigan, ARPA held its yearly meeting of the “principle investigators” from each of its university and other contractors. (ARPA draft, III-25)

Results from the previous year’s research was summarized and future research was discussed, either introduced by ARPA or the various researchers present at the meetings.

Networking was one of the topics brought up at this meeting. (ARPA draft, III-25)

The Completion Report continues the story:

“At the meeting it was agreed that work could begin on the conventions to be used for exchanging messages between any pair of computers in the proposed network, and also on consideration of the kinds of communications lines and data sets to be used.

In particular, it was decided that the inter-host communication ‘protocol’ would include conventions for character and block transmission, error checking and retransmission, and computer and user identification.

Frank Westervelt, then of the University of Michigan, was picked to write a position paper on these areas of communication, an ad hoc ‘Communication Group’ was selected from among the institutions represented, and a meeting of the group scheduled.” (ARPA draft, III-26)

In order to develop this network of varied computers, two main problems had to be solved:

“1. – To construct a ‘subnetwork’ consisting of telephone circuits and switching nodes whose reliability, delay characteristics, capacity, and cost would facilitate resource sharing among computers on the network.

2. – To understand, design, and implement the protocols and procedures within the operating systems of each connected computer, in order to allow the use of the new subnetwork by the computers in sharing resources.” (ARPA draft, II-8)

After one draft and additional work on this communications position paper report, a two-day meeting was scheduled in early October 1967 by ARPA to,

“Discuss the protocol paper and specifications for the Interface Message Processor (IMP).”

The IMP was the decided upon method of connecting the participants computers (hosts) to each other via phone lines.

This standardized the network which the hosts connected to.

Now, only the connection of the hosts to the network would depend on vendor type, etc.

ARPA had picked 19 possible participants in what was now known as the “ARPA Network”, rather than the previously vague descriptions.

After the time of the 1967 PI Meeting, various computer scientists who were ARPA contractors were busy thinking about various aspects which would be relevant to the planning and development of the ARPANET.

Part of that work was a document outlining a beginning design for the IMP network.

This specification would lead to the ability to a put out a competitive procurement for the design of the IMP subnetwork.

“At the end of 1967 ARPA initiated a small contract with the Stanford Research Institute for the development of specifications for the necessary communications system.

Elmer Shapiro was to be the key person on this study.

Published in the final version in December of 1968 was a 71-page SRI report entitled “A Study of Computer Network Design Parameters”, an early version in early 1968 served as the first draft of the IMP specification…

In February or March, a memo written by Shapiro and revised by Kleinrock entitled “Functional Description of the IMP” was circulated.After the first draft by Shapiro, it is believed that Glenn Culler wrote a second draft, and Robert and Wessler of ARPA wrote the final version of the IMP specification.

In any case, by the first of March 1968, IPT was able to report to the Director of ARPA that specifications for the IMP were essentially complete, and that they would be discussed at the upcoming PI meeting with the goal of issuing a Request for Quotation shortly thereafter.

The network was discussed at the PI meeting and by June 1968, the ARPANET procurement officially started. (ARPA draft, III-32)

ARPA’s Program Plan for the ARPANET was titled “Resource Sharing Computer Networks”.

It was submitted June 3, 1968, and approved by the Director June 21, 1968.

The Completion Report explains that the Program Plan was,

“an interesting document.

The stated objectives of the program were to develop experience in interconnection computers and to improve and increase computer research productivity through resource sharing.

Technical needs in scientific and military environments were cited as justification for the program objectives.Relevant prior work was described. It was noted that the computer research centers supported or partially supported by IPT provided a unique testbed for computer networking experiments, as well as providing immediate benefits to the centers and valuable research results to the military.

The network planning that had gone on was described, the need for a network information center was noted, and the network design was sketched.

A five year schedule for network procurement, construction, operation, and transfer out of ARPA was presented.

(It was noteworthy that IPT had initially had in mind eventual transfer of the operational network to a common carrier.)Finally a several-million-dollar, several-year budget was stated.” (ARPA draft, III-35)

“The Defense Supply Service – Washington (DSS-W) agreed to be a procurement agent for ARPA.

At the end of July, the Request for Quotation for network IMPs was mailed to 140 potential bidders who had expressed interest in receiving it.Approximately 100 people from 51 companies attended a subsequent bidders’ conference. Twelve proposals were actually received by DSS_W comprising 6.6 edge-feet of paper and presenting an awesome evaluation task for IPT, which more normally awards contracts on a sole source basis.

Attempting to evaluate the proposals “strictly by the book”, an ARPA-appointed evaluation committee retired to Monterey, California, to carry out their task.

ARPA was pleasantly surprised that several of the respondents believed that they could construct a network which performed as much as a factor of five better than the delay constraint given in the RFQ…” (ARPA draft, III-35)

ARPA developed a program plan, which developed into a set of specifications.

These specifications were connected to a competitive Request for Quotation to find an organization which would design and build the subnetwork between the IMPs.

BBN won the contract to develop the IMP-to-IMP subnetwork.

However, the second technical problem still remained to be solved.

The protocol to allow the hosts to communicate with each other over the subnetwork had to be developed.

This work was left,

“For host sites to work out among themselves.” (ARPA draft, III-67)

This meant that both the hardware and software necessary to connect the hosts to the IMP subnetwork had to be developed.

ARPA assigned this duty to the initial designated ARPANET sites.

As each site had a different type of computer to connect, they individually were the best-informed designers for their personal setups.

In addition, the sites needed to develop the hardware and software necessary to utilize the other hosts on the network. (ARPA draft, III-39)

ARPA’s assigning of responsibilities makes the academic computer science community become an active part of the ARPANET development team. (Interview with Alex McKenize, Nov, 1 1993)

Steve Crocker associates the placement of the initial ARPANET sites at research institutions to the fact that the ARPANET was ground-breaking research.

Crocker in 2007 – Stephen D. Crocker (born October 15, 1944) is an American Internet pioneer. In 1969, he created the ARPA “Networking Working Group” and the Request for Comments series. He served as chair of the board of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) from 2011 through 2017.

He wrote in a message responding to my questions on the COM-PRIV mailing list:

“During the initial development of the Arpanet, there was simply a limit as to how far ahead anyone could see and manage.

The IMPs were placed in cooperative ARPA R&D sites with the hope that these research sites would figure out how to exploit this new communication medium.” (Crocker, 1993A)

The first sites of the ARPANET were picked to provide either network support services or unique resources.

They were also picked as deemed technically able of developing the protocols necessary to make communications between the varied computers connected possible.

The key services the first four sites provided were,

“UCLA – Network Measurement Center SRI – Network Information Center UCSB – Culler-Fried interactive mathematics UTAH – graphics (hidden line removal)” (Cerf, Vinton 1993)

Steve Crocker also recounts that the reason for selecting these particular four sites was because they were,

“Existing ARPA computer science research contractors.”

This was important because,

“The research community could be counted on to take some initiative.” (RFC 1000, pg 1)

The very first site to receive an IMP was UCLA.

Professor Leonard Kleinrock of UCLA was involved with much of the early development of the ARPANET.

Leonard Kleinrock (born June 13, 1934) is an American computer scientist and Internet pioneer. He is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Computer Science at UCLA’s Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science.

His work consisted of understanding queuing theory and as such was one of the first computer scientists working on the ARPANET who was dealing with how to measure what was happening as the network would function.

This made it natural to make sure that UCLA received the first node as it would be important to initiate the network from the site which would measure the networks activity.

In order for the statistics to be correct and for analysis purposes – the first site had to be the measurement site.

Sure enough UCLA was assigned to be the Network Measurement Center (NMC). [1]

[1] These quotes show some of the perspective chosen to pick the initial ARPANET sites.

Part II – The Network Working Group

Once the initial sites were picked, representatives from each site gathered together to start talking about solving the technical problem of getting the hosts to communicate via protocols.

The ARPA Completion report tells us about this beginning:

“To provide the hosts with a little impetus to work on the host-to-host problems.

ARPA assigned Elmer Shapiro of SRI “to make something happen”, a typically vague ARPA assignment.

Shapiro called a meeting in the summer of 1968 which was attended by programmers from several of the first hosts to be connected to the network.

Individuals who were present have said that it was clear from the meeting at that time, no one had even any clear notions of what the fundamental host-to-host issues might be.” (AC Draft III-67 1.4.1.7)

Again, we see that this group, which came to be known as the Network Working Group (NWG), was exploring new territory.

The first meeting took place several months before the first IMP was put together and they had to think from a blank slate.

Throughout the existing recollections of the important developments the NWG produced, (especially RFC 1000) the reader is reminded that the thinking involved was totally original and thus thought-provoking.

Steve Crocker remembers in the RFC Reference Guide (RFC 1000) that the first meeting was chaired by Elmer Shapiro, who initiated the conversation with a list of questions. (Crocker, 1993b)

Also present were,

- Steve Carr from University of Utah

- Stephen Crocker from UCLA

- Jeff Rulifson from SRI

- Ron Stoughton from UCSB

These attendees are the programmers referred to in the ARPANET Completion Report.

In the words of Steve Crocker, this was a seminal meeting.

The attendees could only be but theoretical, as none of the lowest levels of communication had been developed yet.

They needed a transport layer or low-level communications platform to be able to build upon. BBN did not deliver the first IMP until August 30, 1969.

It was important to meet beforehand, as the NWG “imagined all sorts of possibilities.” (Rfc1000)

Only once their thought processes started could this working group actually develop anything. These fresh thoughts from fresh minds help to incubate new ideas.

The ARPANET Completion Report properly acknowledges what this early group helped accomplished:

“Their early thinking was at a very high level.” (ARPA draft, III-67)

A concrete decision of the first meeting was to continue holding meetings similar to the first one. This wound up setting the precedent of a holding exchange meetings at each of the sites.

Steve Crocker, describing the problems facing these networking pioneers, writes:

“With no specific service definition in place for what the IMPs were providing to the hosts, there wasn’t any clear idea of what work the hosts had to do.

Only later did we articulate the notion of building a layered set of protocols with general transport services on the bottom and multiple application- specific protocols on the top.

More precisely, we understood quite early that we wanted quite a bit of generality, but we didn’t have a clear idea how to achieve it.

We struggled between a grand design and getting something working quickly.” (Crocker,1993c)

The initial protocol development led to DEL (Decode-Encode-Language) and NIL (Network-Interchange-Language).

These languages were ahead of their time.

The basic purpose was to form an on-the-fly description that would tell the receiving end how to understand the information that would be sent.

However, these first set of meetings were extremely abstract as neither ARPA nor the universities had deemed any official charter.

The lack of a charter allowed the group to think broadly and openly however.

BBN did submit details as to the host-IMP interface specifications from the IMP side.

This information provided the group some definite starting points to build from.

Soon after BBN provided more information, on Valentine’s Day, 1969, members of the NWG, members of BBN and members of the Network Analysis Corporation (NAC) met for the first time.

[The NAC was contracted by ARPA to “specify the topological design of the ARPANET and to analyze its cost, performance, and reliability characteristics. (ARPA not draft, III-30)]

As all the parties had different priorities on mind, the meeting was a difficult one. BBN was interested in the lowest level of making a reliable connection.

The programmers from the host sites were interested in getting the hosts to communicate with each either via various higher level programs.

And BBN also did not turn out to be the “experts from the East” that Steve Crocker wrote the members of the NWG expected.

He continues by writing in RFC 1000 that they constantly thought that,

“A professional crew would show up eventually to take over the problems we were dealing with.”

A step of incredible importance and openness occurred as a result from a “particularly delightful” meeting that took place a month later in Utah. (RFC1000)

The participants decided it was time to start recording their meetings in a consistent fashion. What resulted was a set of informal notes titled “Request for Comments.”

Steve Crocker writes about their formation:

“I remember having great fear that we would offend whomever the official protocol designers were, and I spent a sleepless night composing humble words for our notes.

The basic ground rules were that anyone could say anything and that nothing was official.

And to emphasize the point, I labeled the notes “Request for Comments.”I never dreamed these notes would be distributed through the very medium we were discussing in these notes. Talk about Sorcerer’s Apprentice!” (Crocker, RFC 1000, pg 3, 1987)

Crocker replaced Shapiro as the Chairman of the NWG after the initial meeting.

“Over the spring and summer of 1969 we grappled with the detailed problems of protocol design.

Although we had a vision of the vast potential for intercomputer communication, designing usable protocols was another matter.

A custom hardware interface and custom intrusion into the operating system was going to be required for anything we designed, and we anticipated serious difficulty at each of the sites.

We looked for existing abstractions to use.

It would have been convenient if we could have made the network simply look like a tape drive to each host, but we knew that wouldn’t do.” (Crocker, RFC 1000, pg. 3)

He describes how they wrestled with creation of the host-host protocols:

The first two IMPs were delivered to UCLA (number 1) and SRI (Number 2).

Once two IMPs existed, the NWG had to implement a working protocol.

This first set of host protocols included a remote login for interactive use (telnet), and a way to copy files between remote hosts (FTP).

File Transfer Protocol – Wikipedia

Crocker writes:

“In particular, only asymmetric, user-server relationships were supported.

In December 1969, we met with Larry Roberts in Utah, [and he] made it abundantly clear that our first step was not big enough, and we went back to the drawing board.

Lawrence Gilman Roberts (December 21, 1937 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer who received the Draper Prize in 2001 “for the development of the Internet”, and the Principe de Asturias Award in 2002.

Over the next few months, we designed a symmetric host-host protocol, and we defined an abstract implementation of the protocol known as the Network Control Program.

(“NCP” later came to be used as the name for the protocol, but it originally meant the program within the operating system that managed connections.

The protocol itself was known blandly only as the host-host protocol.)

Along with the basic host-host protocol, we also envisioned a hierarchy of protocols, with Telnet, FTP and some splinter protocols as the first examples.

If we had only consulted the ancient mystics, we would have seen immediately that seven layers were required.” (RFC 1000, pg 4)

After Robert’s guidance, the Network Working Group went forward in developing the protocols necessary to make the network viable.

The group swelled in attendance as more and more sites connected to the ARPANET.

The group became large enough (around 100 people) that one meeting was held in conjunction with the 1971 Spring Joint Computer Conference in Atlantic City.

A major test of the NWG’s work came in October 1971, when a meeting was held at MIT.

Crocker continues the story,

“[A] major protocol “fly-off” – Representatives from each site were on hand, and everyone tried to log in to everyone else’s site.

With the exception of one site that was completely down, the matrix was almost completely filled in, and we had reached a major milestone in connectivity.” (Crocker, RFC 1000, pg. 4)

The NCP was created as what was called the “host to host protocol.”

Explaining why this was important, the authors of the ARPA draft write:

“The problem is to design a host protocol which is sufficiently powerful for the kinds of communication that will occur and yet can be implemented in all of the various different host computer systems.

The initial approach taken involved an entity called a “Network Control Program” which would typically reside in the executive of a host, such that processes within a host would communicate with the network through this Network Control Program.

The primary function of the NCP is to establish connections, break connections, switch connections, and control flow.

A layered approach was taken such that more complex procedures (such as File Transfer Procedures) were built on top of similar procedures in the host Network Control Program.” (Arpa draft, II-24)

As the ARPANET grew, the number of Users bypassed the number of developers.

This signaled the success of these networking pioneers. Steve Crocker appointed Alex McKenize and Jon Postel to replace him as Chairmen of the Network Working Group.

The Completion Report details how this role changed:

“McKenzie and Postel interpreted their task to be one of codification and coordination primarily, and after a few more spurts of activity the protocol definition process settled for the most part into a status of a maintenance effort.” (ARPA draft, III-69)

ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) was a management body which lent funding to academic computer scientists.

ARPA’s smart management sense paved the way for these scientists to create the ARPANET.

BBN helped via developing the packet switching techniques most suitable to passing a wide variety of information.

However, the most important development was that of the “Request for Comments” documentation.

Part III – About RFC’s as “Open” Documentation

The openness initiated from the very first meeting of the Network Working Group (NWG) continued on in a more informal formalized manner in the Request For Comments.

As meeting notes, the RFCs were meant to keep members updated on the status of several things.

They were also meant to gather responses from people.

The Documentation Conventions RFC (RFC 3) documents the “rules” governing the production of these notes.

Topping the page were the open distribution rules:

“Documentation of the NWG’s effort is through notes such as this.

Notes may be produced at any site by anybody and included in this series.”

The guide goes on to describe the rules concerning the contents of the RFCs:

“The content of a NWG note may be any thought, suggestion, etc. related to the HOST software or other aspect of the network.

Notes are encouraged to be timely rather than polished.Philosophical positions without examples or other specifics, specific suggestions or implementation techniques without introductory or background explication, and explicit questions without any attempted answers are all acceptable.

The minimum length for a NWG note is one sentence.”

The RFC continues to explain the philosophy behind the unprecedented amount of openness represented:

“These standards (or lack of them) are stated explicitly for two reasons.

First, there is a tendency to view a written statement as ipso facto authoritative, and we hope to promote the exchange and discussion of considerably less than authoritative ideas.

Second, there is a natural hesitancy to publish something unpolished, and we hope to ease this inhibition.” (Crocker, RFC 3 – 1969) [The entire RFC is reproduced in the Appendix B.]

This openness led to the exchange of information.

These open principles are what made the development of the Net possible.

Statements like the ones contained in RFC 3 are very progressive in their openness.

Late 1960’s was a time awash in popular protest for freedom of speech and demanding more of a say of how the country is run.

The openness contained in trying to develop new technologies fits well with the cry for more democracy which students demanded throughout the country and the world.

What is amazing is that the collaboration of the NWG (mostly graduate students) and ARPA (a component of the military), seems to be contrary to the normal atmosphere of the times.

Robert Braden of the Internet Activities Board reflects on this collaboration:

“For me, participation in the development of the ARPAnet and the Internet protocols has been very exciting.

One important reason it worked, I believe, is that there were a lot of very bright people all working more or less in the same direction, led by some very wise people in the funding agency.The result was to create a community of network researchers who believed strongly that collaboration is more powerful than competition among researchers.

I don’t think any other model would have gotten us where we are today.” (RFC 1336)

What is even more important is the work of these computer scientists founded what has lead to the most amazing and democratic body (i.e.: The Net and the culture attached to it) to emerge in long time.

The community that has developed and the tools which accompany it form an important democratic force.

The idea of calling these notes a “Request for Comment” is a fascinating tradition.

It predates the Usenet Post, which in a fashion could be called a “request for comment” as it is the presentation of a particular person’s ideas, questions or comments, to the general public (of those who read that newsgroup) for comments, criticism or suggestion, or just plain to further the readers’ knowledge.

Other Early RFCs echo this reality.

There exist RFCs which are in response to previous RFCs.

Following are some examples, more are contained in the appendix.

65 Walden, D. Comments on Host/Host Protocol document #1 1 Crocker, S. Host software 1969 April 7

39 Harslem, E.; Heafner, J. Comments on protocol re: NWG/RFC #36 38 Wolfe, S. Comments on network protocol from NWG/RFC #36 36 Crocker, S. Protocol notes 1970 March 16

47 Crowther, W. BBN’s comments on NWG/RFC #33 1970 April 20 33 Crocker, S. New Host-Host Protocol 1970 February 12

Part IV – Conclusion

The Network Working Group’s development of open technical documentation – the RFC – was a necessary step to technical advancement.

Steve Crocker explains the importance of openness in a developmental situation:

“The environment we were operating in was one of open research.

The only payoff available was to have good work recognized and used.

Software was generally considered free.

Openness wasn’t an option; it just was.” (Crocker, 1993c)

The NWG’s work was important (THE?) to the development of the ARPANET.

Their work paved the way for the development of TCP/IP, when more capacity was needed, and other problems arose.

I would call the RFC one of the Heralding Achievements of the NWG.

It represents the forward-looking view which these people had, and it proved to succeed.

The principles which embody RFC 3 foreshadowed the success of TCP/IP from NCP’s influence.

Both TCP/IP and NCP were developed in the field.

A version of the protocols would be released for experimentation and use.

Also, all specifications were available free and easily available for people to examine and make comments about.

Only through this early release were the problems and kinks found and worked out in a timely manner.

This bottom-up approach is substantially different than the top-down approach which other protocol suites have been developed under.

The top-down idea comes from figuring everything out as a standard on paper, or behind closed doors and then releasing it to be used.

The bottom-up (and free accessibility of protocol documentation and specifications) model allows for a wide-range of people and experiences to join in and perfect the protocol and make it the best possible. (Check email in TCPIP.MAIL file to provide quotes.)

In summing up the achievements of the process that developed the ARPANET, the ARPANET Completion Report draft explains:

“The ARPANET development was an extremely intense activity in which contributions were made by many of the best computer scientists in the United States.

Thus, almost all of the “major technical problems” already mentioned received continuing attention and the detailed approach to those problems changed” [II-24]

The computer scientists and others involved were encouraged in their work by the ARPA philosophy of gathering the best computer scientists working in the field and supporting them:

“IPT usually does little day-to-day management of its contractors.

Especially with its research contracts, IPT would not be producing faster results with such management as research must progress at its own pace.IPT has generally adopted a mode of management which entails finding highly motivated, highly skilled contractors, giving them a task, and allowing them to proceed by themselves.” (III-47)

The result, explained by the Completion Report was a new way of looking at computers as communications devices rather than as arithmetic devices.

Yet many computer science department still do not understand this significance today.

End Notes

“CCN’s [The Campus Computing Network of UCLA] chance to obtain a connection to the ARPANET was a result of the presence at UCLA of Professor L. Kleinrock and his students, including:

- S. Crocker

- J. Postel

- V. Cerf

This group was not only involved in the original design of the network and the Host protocols, but also was to operate the Network Measurement Center (NMC).

For these reasons the first delivered IMP was installed at UCLA, and ARPA was thus able to easily offer CCN the opportunity for connection.”

“In a somewhat less structured way, the research groups receiving ARPA IPTO support were then encouraged to begin considering the design and implementation of protocols and procedures and, in turn, computer program modifications, in the various host computers in order to use the subnetwork.

Several specific responsibilities were arranged: UCLA was specifically asked to take on the task of a “Network Measurement Center” with the objective of studying the performance of the network as it was built, grown, and modified; SRI was specifically asked to take on the task of a “Network Information Center” with the objective of collecting information about the network, about host resources, and at the same time generating computer based tools for storing and accessing that collected information.

Beyond these two specific contracts, some rather ad hoc mechanisms were pursued to reach agreement between the various research contractors about the appropriate “host protocols” for intercommunicating over the subnetwork.

The “Network Working Group” of interested individuals from the various host sites was rather informally encouraged by ARPA.

After a time, this Network Working Group became the forum for, and eventually a semi-official approval authority for, the discussion of and…”

The Network Information Center

“The accessibility of distributed resources carries with it the need for an information service (either centralized or distributed) that enables users to learn about those resources.

This was recognized at the PI [ed. Primary Instigators] meeting in Michigan in the spring of 1967.

At the time, Doug Engelbart and his group at the Stanford Research Institute were already involved in research and development to provide a computer-based facility to augment human interaction.

Engelbart in 2008 – Douglas Carl Engelbart (January 30, 1925 – July 2, 2013) was an American engineer and inventor, and an early computer and Internet pioneer. He is best known for his work on founding the field of human–computer interaction, particularly while at his Augmentation Research Center Lab in SRI International, which resulted in creation of the computer mouse, and the development of hypertext, networked computers, and precursors to graphical user interfaces.

Thus, it was decided that Stanford Research Institute would be a suitable place for a “Network Information Center” (NIC) to be established for the ARPANET.

With the beginning of implementation of the network in 1969, construction also began on the NIC at SRI.”

RFC 1000 reports on the process of the installation of the first IMP

“[T]ime was pressing: The first IMP was due to be delivered to UCLA September 1, 1969, and the rest were scheduled at monthly intervals.

At UCLA we scrambled to build a host-IMP interface. SDS, the builder of the Sigma 7, wanted many months and many dollars to do the job.

Mike Wingfield, another grad student at UCLA, stepped in and offered to get interface built in six weeks for a few thousand dollars.

He had a gorgeous, fully instrumented interface working in five and one half weeks.

I was in charge of the software, and we were naturally running a bit late.

September 1 was Labor Day, so I knew I had a couple of extra days to debug the software.

Moreover, I had heard BBN was having some timing troubles with the software, so I had some hope they’d miss the ship date.

And I figured that first some Honeywell people would install the hardware – IMPs were built out of Honeywell 516s in those days – and then BBN people would come in a few days later to shake down the software.

An easy couple of weeks of grace.

BBN fixed their timing trouble, air shipped the IMP, and it arrived on our loading dock on Saturday, August 30.

They arrived with the IMP, wheeled it into our computer room, plugged it in and the software restarted from where it had been when the plug was pulled in Cambridge.

Still Saturday, August 30.

Panic time at UCLA.

The second IMP was delivered to SRI at the beginning of October, and ARPA’s interest was intense.

Larry Roberts and Barry Wessler came by for a visit on November 21, and we actually managed to demonstrate a Telnet-like connection to SRI.”

Documentation Conventions

The Network Working Group seems to consist of,

- Steve Carr of Utah

- Jeff Rulifson and Bill Duvall at SRI

- Steve Crocker and Gerard Deloche at UCLA

Membership is not closed.

The Network Working Group (NWG) is concerned with the HOST software, the strategies for using the network, and initial experiments with the network.

Documentation of the NWG’s effort is through notes such as this.

Notes may be produced at any site by anybody and included in this series.

CONTENT

The content of a NWG note may be any thought, suggestion, etc. related to the HOST software or other aspect of the network.

Notes are encouraged to be timely rather than polished.

Philosophical positions without examples or other specifics, specific suggestions or implementation techniques without introductory or background explication, and explicit questions without any attempted answers are all acceptable.

The minimum length for a NWG note is one sentence.

These standards (or lack of them) are stated explicitly for two reasons.

- First, there is a tendency to view a written statement as ipso facto authoritative, and we hope to promote the exchange and discussion of considerably less than authoritative ideas.

- Second, there is a natural hesitancy to publish something unpolished, and we hope to ease this inhibition.

FORM

Every NWG note should bear the following information:

- “Network Working Group” “Request for Comments:” x where x is a serial number. Serial numbers are assigned by Bill Duvall at SRI

- Author and affiliation

- Date

- Title. The title need not be unique

DISTRIBUTION

One copy only will be sent from the author’s site to”,

1. Bob Kahn, BB&N 2. Larry Roberts, ARPA 3. Steve Carr, UCLA 4. Jeff Rulifson, UTAH 5. Ron Stoughton, UCSB 6. Steve Crocker, UCLA

Reproduction if desired may be handled locally.

OTHER NOTES

Two notes (1 & 2) have been written so far.

These are both titled HOST Software and are by Steve Crocker and Bill Duvall, separately.

Other notes planned are on,

1. Network Timetable

2. The Philosophy of NIL

3. Specifications for NIL

4. Deeper Documentation of HOST Software

Listing of RFCs that are Comments

238 “Comments on DTP and FTP proposals”

1453 A Comment on Packet Video Remote Conferencing and the Transport/Network

47 BBN’s comments on NWG/RFC #33

489 Comment on resynchronization of connection status proposal

684 Commentary on procedure calling as a network protocol

176 Comments on “Byte size for connections”

368 Comments on “Proposed Remote Job Entry Protocol”

175 Comments on “Socket conventions reconsidered”

151 Comments on a proffered official ICP: RFCs 123, 127

535 Comments on File Access Protocol

430 Comments on File Transfer Protocol

65 Comments on Host/Host Protocol document #1

692 Comments on IMP/Host Protocol changes (RFCs 687 and 690)

224 Comments on Mailbox Protocol

68 Comments on memory allocation control commands: CEASE, ALL, GVB, RET,RFNM 1970 August 31

773 Comments on NCP/TCP mail service transition strategy

38 Comments on network protocol from NWG/RFC #36

44 Comments on NWG/RFC 33 and 36

623 Comments on on-line host name service

39 Comments on protocol re: NWG/RFC #36

718 Comments on RCTE from the Tenex implementation experience

141 Comments on RFC 114: A File Transfer Protocol

127 Comments on RFC 123

148 Comments on RFC 123

582 Comments on RFC 580: Machine readable protocols

393 Comments on Telnet Protocol changes

385 Comments on the File Transfer Protocol

607 Comments on the File Transfer Protocol

624 Comments on the File Transfer Protocol

696 Comments on the IMP/Host and Host/IMP Protocol changes

50 Comments on the Meyer proposal

559 Comments on the new Telnet Protocol and its implementation

513 Comments on the new Telnet specifications

690 Comments on the proposed Host/IMP Protocol changes

563 Comments on the RCTE Telnet option

463 FTP comments and response to RFC 430

40 More comments on the forthcoming protocol

1111 Request for comments on Request for Comments: Instructions to RFC Authors

129 Request for comments on socket name structure

614 Response to RFC 607: “Comments on the File Transfer Protocol”

1018 Some comments on SQuID

117 Some comments on the official protocol

1000 THE REQUEST FOR COMMENTS REFERENCE GUIDE

531 Feast or famine? A response to two recent RFC’s about network information 1973 June 26

463 FTP comments and response to RFC 430

613 Network connectivity: A response to RFC 603 Network connectivity a response to RFC 603

685 Response time in cross network debugging

135 Response to NWG/RFC 110

355 Response to NWG/RFC 346

73 Response to NWG/RFC 67

130 Response to RFC 111: Pressure from the chairman

131 Response to RFC 116: May NWG meeting

29 Response to RFC 28

492 Response to RFC 467

568 Response to RFC 567 – cross country network bandwidth

603 Response to RFC 597: Host status

614 Response to RFC 607: “Comments on the File Transfer Protocol”

125 Response to RFC 86: Proposal for network standard format for a graphics data stream 1971 April 18

555 Responses to critiques of the proposed mail protocol

156 Status of the Illinois site: Response to RFC 116

112 User/Server Site Protocol: Network host questionnaire responses

LINKS

CONTINUE

DARPA: Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – Library of Rickandria

SAUCE

History of ARPANET – Behind The Net (bibliotecapleyades.net)