Hiroshima & Nagasaki: A Canaanite Experiment

It was only after the war that the American public learned about Japan’s efforts to bring the conflict to an end.

Chicago Tribune reporter Walter Trohan, for example, was obliged by wartime censorship to withhold for seven months one of the most important stories of the war.

In an article that finally appeared August 19, 1945, on the front pages of the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Times-Herald, Trohan revealed that on January 20, 1945, two days prior to his departure for the Yalta meeting with Stalin and Churchill, President Roosevelt received a 40-page memorandum from General Douglas MacArthur outlining five separate surrender overtures from high-level Japanese officials.

(The complete text of Trohan’s article is in the Winter 1985-86 Journal, pp. 508-512.)

This memo showed that the Japanese were offering surrender terms virtually identical to the ones ultimately accepted by the Americans at the formal surrender ceremony on September 2 — that is, complete surrender of everything but the person of the Emperor.

Specifically, the terms of these peace overtures included:

• Complete surrender of all Japanese forces and arms, at home, on island possessions, and in occupied countries.

• Occupation of Japan and its possessions by Allied troops under American direction.

• Japanese relinquishment of all territory seized during the war, as well as Manchuria, Korea and Taiwan.

• Regulation of Japanese industry to halt production of any weapons and other tools of war.

• Release of all prisoners of war and internees.

• Surrender of designated war criminals. [1]

Few people can comprehend the extent of horrors that resulted from the use of atomic weapons.

The civilians of Hiroshima were attacked early in the morning.

Citizens were getting ready to go to their jobs, children were preparing for school, and no one was aware of what was to come.

When Colonel Tibbits dropped the bomb, the shock waves were so intense that they knocked the plane about in the sky.

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the Enola Gay (named after his mother) when it dropped a Little Boy, the first of two atomic bombs used in warfare, on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Tibbets enlisted in the United States Army in 1937 and qualified as a pilot in 1938. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he flew anti-submarine patrols over the Atlantic. In February 1942, he became the commanding officer of the 340th Bombardment Squadron of the 97th Bombardment Group, which was equipped with the Boeing B-17. In July 1942, the 97th became the first heavy bombardment group to be deployed as part of the Eighth Air Force, and Tibbets became deputy group commander. He flew the lead plane in the first American daylight heavy bomber mission against German-occupied Europe on 17 August 1942, and the first American raid of more than 100 bombers in Europe on 9 October 1942. Tibbets was chosen to fly Major General Mark W. Clark and Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower to Gibraltar. After flying 43 combat missions, he became the assistant for bomber operations on the staff of the Twelfth Air Force. Tibbets returned to the United States in February 1943 to help with the development of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. In September 1944, he was appointed the commander of the 509th Composite Group, which would conduct the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, he participated in the Operation Crossroads nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946 and was involved in the development of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet in the early 1950s. He commanded the 308th Bombardment Wing and 6th Air Division in the late 1950s and was military attaché in India from 1964 to 1966. After leaving the Air Force in 1966, he worked for Executive Jet Aviation, serving on the founding board and as its president from 1976 until his retirement in 1987. After the war he received wide publicity, including motion picture portrayals, and became a symbolic figure in the debate over the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

The area where the bomb hit; the center was as hot as the surface of the sun.

People melted into walls, only the shadows of their charred images remained.

The plight of the survivors was even far worse.

The skin peeled right off of the bones of the many who were still living.

Hair fell out of their heads in clumps.

Fetuses fell right out of the abdomens of pregnant women.

Many others suffered third degree burns and long-term horrendous effects, such as keloid scars caused by thermal radiation.

President Truman steadfastly defended his use of the atomic bomb, claiming that it “saved millions of lives” by bringing the war to a quick end.

Justifying his decision, he went so far as to declare:

“The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.”

This was a preposterous statement.

In fact, almost all of the victims were civilians, and the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (issued in 1946) stated in its official report:

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen as targets because of their concentration of activities and population.”

If the atomic bomb was dropped to impress the Japanese leaders with the immense destructive power of a new weapon, this could have been accomplished by deploying it on an isolated military base. It was not necessary to destroy a large city.

And whatever the justification for the Hiroshima blast, it is much more difficult to defend the second bombing of Nagasaki.

After the July 1943 firestorm destruction of Hamburg, the mid-February 1945 holocaust of Dresden, and the fire-bombings of Tokyo and other Japanese cities, America’s leaders — as US Army General Leslie Groves later commented —

“Were generally inured to the mass killing of civilians.” [2]

“The experiment has been an overwhelming success,”

President Harry S. Truman reportedly told his shipmates upon learning that the U.S. military had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

UFO intercepted a nuclear warhead in the USA in 1964 – Library of Rickandria

“After the bombings, Japanese filmmakers attempted to document the horror that the atomic bombs left in Japan.

Recognizing this as a potential threat, the U.S. military seized all Japanese footage and then placed an order banning all future filming.” [3]

Hiroshima and Nagasaki fact and fiction:

Lie:

Leaflets were dropped on Japanese cities to warn civilians to evacuate.

Truth:

Leaflets were dropped after we bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Lie:

Our use of the atomic bombs shortened the war.

Truth:

The Japanese were looking for peace when they returned from the Potsdam Conference on Aug. 3, 1945, three days before the U.S. military bombed Hiroshima.

Lie:

We bombed Hiroshima, which was an important Japanese Army base.

Truth:

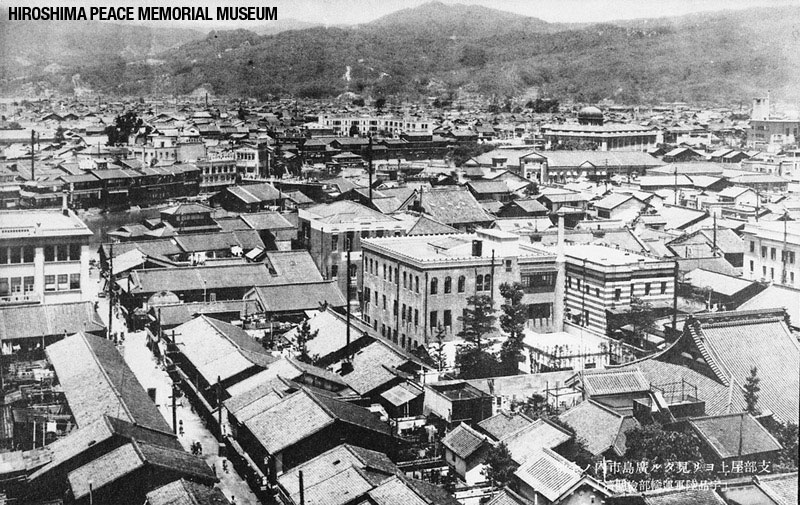

We bombed the city center of Hiroshima, which had a population of 350,000.

Truth:

Only four of the 30 targets were, in fact, military in nature. [4]

In truth, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were experiements, masterminded, and advocated by Jews.

“We may never actually have to use this atomic weapon in military operations as the mere threat of its use will persuade any opponent to surrender to us.” – Chaim Weizmann [Jew]

Chaim Azriel Weizmann (/ˈkaɪm ˈwaɪtsmən/ KYME WYTE-smən; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israeli statesman who served as president of the Zionist Organization and later as the first president of Israel. He was elected on 16 February 1949 and served until his death in 1952. Weizmann was instrumental in obtaining the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and convincing the United States government to recognize the newly formed State of Israel in 1948. As a biochemist, Weizmann is considered to be the ‘father’ of industrial fermentation. He developed the acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation process, which produces acetone, n-butanol and ethanol through bacterial fermentation. His acetone production method was of great importance in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants for the British war industry during World War I. He founded the Sieff Research Institute in Rehovot (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science in his honor) and was instrumental in the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

References:

1 Institute for Historical Review Article: Was Hiroshima Necessary? Why the Atomic Bombings Could Have Been Avoided by By Mark Weber

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

CONTINUE

Miles Williams Mathis: The Nuclear Hoax – Library of Rickandria