Fate & Free Will: The Stoic Perspective

by Mariami Shanshashvili on September 08, 2021, from ClasicalWisdom Website

It is no secret that ancient teachings of Stoicism have seen a massive revival in modern times.

From academia to the general public, people have been closely rethinking Stoic philosophy.

One of the primary reasons behind this surging popularity of Stoicism, I would say, is the appeal of exercising a complete control over your mind.

It is true that Stoic practices allow us the greater freedom over our psyche and emotions.

One area, however, where Stoicism does not spoil us with as much freedom, is the freedom of will.

When it comes to fate and free will in Stoicism, a key debate exists between,

what’s referred to as the ‘Lazy Argument’ from critics of Stoicism.

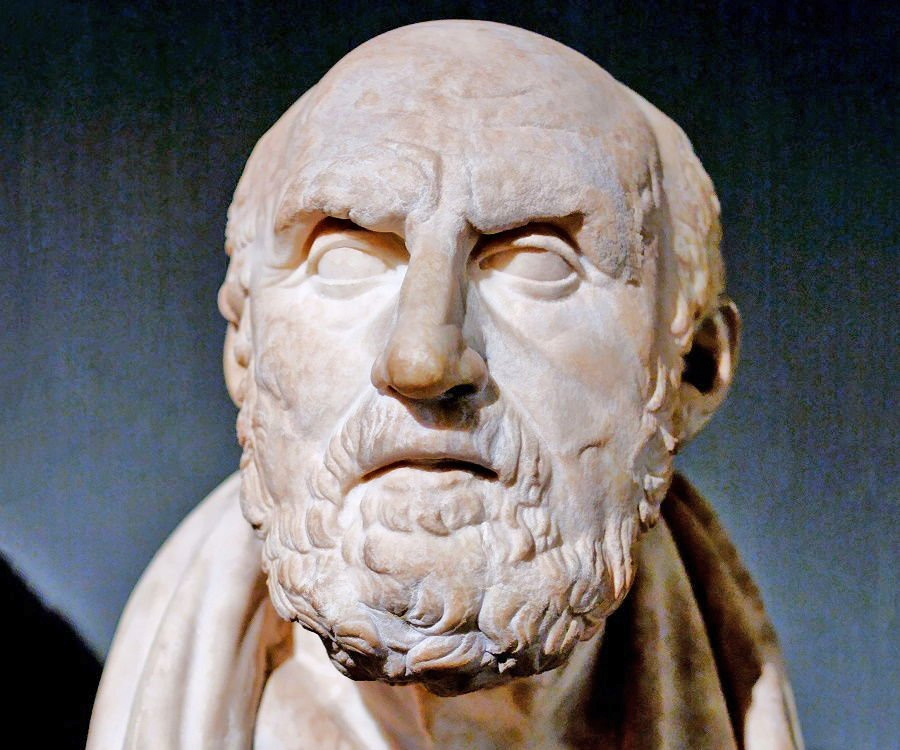

and the Stoic Response to the Lazy Argument developed by the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus…

By examining this debate, we can gain a better insight into the truth of the Stoic understanding of fate and freedom.

Ancient Stoics believed in a causal or ‘soft’ determinism:

a view that maintains that everything that happens has a cause that leads to an effect.

Each and every event is a part of the unbreakable chain of cause and effect, which is dictated and steered by the gods’ providential plan of fate.

Nevertheless Stoics, however, also assert that even in a deterministic world, our actions are ultimately ‘up to us’.

The Lazy Argument attacks this claim by attempting to show the futility of any action in the face of fate.

The argument is formulated in the following way:

- If it is fated that you will survive a snakebite, then you will survive whether you go to a hospital or not.

- Likewise, if you are fated to not survive a snakebite, then you will not survive whether you go to a hospital or not.

- One of them is fated.

- On either alternative, it does not matter what you do because the fated outcome will happen anyway.

The essence of the Lazy Argument is to demonstrate how no action matters if every event is fated.

And since your life is set to unwaveringly follow a determined track, there is no point to exert any effort or even think about the right course of action.

Simply put, the Lazy Argument makes just being lazy an appealing choice…

The Stoic response, attributed to Chryssipus by Cicero in his De Fatō, is designed to show that the Lazy Argument is unsound, and our actions indeed do have a bearing on the outcome of events.

According to Chryssipus, not all premises of the Lazy Argument is true.

Ancient Stoics accept that everything is fated but dismiss the rest the argument.

To say something is fated to happen does not mean that it will happen regardless of what you do.

Rather, to the Stoics it means that this event is a part of the unbreakable cause-effect chain in which some causal elements are crucial for bringing about the effect.

Moreover, knowing that the outcome is fated does not give you any insight into what actions lead up to it.

Some events, claims Chryssipus, are co-fated, meaning that they are interconnected and conjoined to the others.

The prophecy of Laius, the father of Oedipus, is a telling example of this concept:

Laius was warned by the oracle that he would be killed by his own son.

But this would not happen if he did not beget a child.

Simply put,

Laius’ end is co-fated with begetting Oedipus, which is in turn co-fated with having intercourse with a woman.

It is not true that Laius will still meet the same end whether or not he has a child.

The course of fate, therefore, does not necessarily dispose of the causal relationship between the events.

Quite the opposite, the Stoic fate is remarkably logical:

it is operating under the sound logic of ’cause and effect’.

Therefore, according to the Stoics, the claim of the Lazy Argument that a certain event will occur no matter what we do grossly overlooks the necessary connections between events.

So, to put it another way, if we want to survive the snakebite, we really better go to a hospital.

Some might argue that the objection of whether or not our actions are ‘up to us’ is a completely different objection.

The Stoic response is taking the Lazy Argument as a question of mechanical correspondence between cause-effect, while what the argument is actually drawing on is how the absence of agency or choice over our actions renders any choice meaningless.

One way or another, Stoics have much more to say about the choice and agency.

Let us consider the Stoic argument through the lens of objection raised by Stoic scholar Keith Seddon:

“Though seeing [two events being co-fated] doesn’t to any degree undermine the fatalist’s position, for just as your recovering was fated (if only you had known it), so was your calling the doctor!

This might be how it happened, all right, but if the event of your calling the doctor was caused by prior circumstances (as all events are, according to the theory of causal determinism) then, in what sense could you be considered to exercise your free will?”

(2004, “Do the Stoics Succeed?”).

Keith Seddon (University College London (PhD)) – PhilPeople

Stoics would say that the matter is more complicated, as the same phenomena can have different effects on different agents.

Chryssipus illustrates this with the following metaphor:

“if you push a cylinder and a cone, the former will roll in a straight line, and the latter in a circle (LS 62C). [1]

Similarly, different men will assent differently to the same push.

And assent, just as we said in the case of the cylinder, although prompted from outside, will thereafter move through its own force and nature.” [2]

Therefore,

our internal nature shapes the way we respond to the external stimuli…

Simply put,

character is fate, with the further inference being that our character itself is determined.

I think the most successful Stoic response to the Lazy Argument is their dog analogy:

“When a dog is tied to a cart, if it wants to follow it is pulled and follows, making its spontaneous act coincide with necessity, but if it does not want to follow it will be compelled in any case.

So, it is with men too: even if they do not want to, they will be compelled in any case to follow what is destined.”

(Hippolytus, Refutation of all heresies 1.21, L&S 62A).

In other words, nothing is up to you, except,

the way you react to it…

A very Stoic thought…!

Bibliography

Tim O’Keefe – The Stoics of Fate and Freedom, the Routledge Companion to Free Will – eds. Meghan Griffith, Neil Levy, and Kevin Timpe, 2016.

A. A. Long and D. N. Sedley – “The Hellenistic Philosophers” – (Cambridge, 1987). Cicero, On Fate

Brennan, T. (2005-06-23) – The Lazy Argument in The Stoic Life: Emotions, Duties, and Fate – Oxford University Press.

References

A. A. Long and D. N. Sedley – The Hellenistic Philosophers – (Cambridge, 1987).

On Fate 42-3 (SVF 2.974; LS 62C(5)–(9))

SAUCE:

Fate and Free Will – The Stoic Perspective (bibliotecapleyades.net)