The Sumerian Swindle – How the Jews Betrayed Mankind – (5000 BC to 1500 BC) – Chapter 8: The Apiru, the Hapiru, the Habiru, the Hebrew 1520 BC

Let’s leave the great empire of Babylonia to its demise around 300 BC and go backward in time once again to where we left the Hyksos goat-rustlers who had escaped from Egypt in 1550 BC.

Once Pharaoh Ahmose, founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1292 BC), had chased the Hyksos out of Egypt and had re-established Egyptian rule, he continued to solidify and protect his country by leading expeditions into Canaan and Syria.

For thousands of years, Egypt had been satisfied with its quests for immortality within its Nile Valley and its desert environs.

But now that Egypt had been violated by the Babylonian money-grubbers and their dirty Hyksos goat-rustlers, Egypt wanted a bigger buffer of protective territory.

Although the Hyksos sheep stealers were too scattered in the hilly regions to make chasing after them a priority, the established towns and cities of Canaan were worth the military effort to show the Canaanites that Egypt would not accept their depredations.

Those Hyksos who had been trapped and enslaved in Egypt were given the Egyptian name for “peasant workers” and “slaves” which was “Apiru”.

As the Egyptian army dealt with the Hyksos who had scampered off into the wilderness with their loot, chasing them away from Egyptian territory in Canaan, they were still called Apiru by the Egyptians.

Thus, the people of Canaan also called these bandits Apiru.

In this way, the Egyptian word took on a new meaning among the Canaanites.

It meant “bandit and cutthroat” because that is what these goat-rustlers were.

By pushing his military campaign into the Near East, Pharaoh Ahmose set a precedent for most Egyptian kings for the next five centuries.

During Ahmose’s reign, Upper and Lower Egypt were once again unified, and Egypt became one of the main Near Eastern powers.

His reign is therefore seen as the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the beginning of the New Kingdom.

A new and great era had dawned for Egypt.

The Eighteenth Dynasty is perhaps the best known of all the dynasties of ancient Egypt and it was led by a number of Egypt’s most powerful pharaohs.

To put this time frame into focus, here is a short list of the Pharaohs important to our study.

This might seem a bit tedious, but it’s necessary background information to link subsequent events together.

Ahmose (1550-1525 BC) was succeeded by his son, Amenhotep I (1526-1506 BC), who was later revered for founding the institution responsible for building the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

Amenhotep I (/ˌæmɛnˈhoʊtɛp/) or Amenophis I (/əˈmɛnoʊfɪs from Ancient Greek Ἀμένωφις), was the second Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. His reign is generally dated from 1526 to 1506 BC (Low Chronology).

Amenhotep I probably left no male heir and the next Pharaoh, Thutmose I (1506-1493 BC), seems to have been related to the royal family through marriage.

Thutmose I (sometimes read as Thutmosis or Tuthmosis I, Thothmes in older history works in Latinized Greek; meaning “Thoth is born”) was the third pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He received the throne after the death of the previous king, Amenhotep I. During his reign, he campaigned deep into the Levant and Nubia, pushing the borders of Egypt farther than ever before in each region. He also built many temples in Egypt, and a tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings; he is the first king confirmed to have done this (though Amenhotep I may have preceded him). Thutmose I’s reign is generally dated to 1506–1493 BC, but a minority of scholars—who think that astrological observations used to calculate the timeline of ancient Egyptian records, and thus the reign of Thutmose I, were taken from the city of Memphis rather than from Thebes—would date his reign to 1526–1513 BC. He was succeeded by his son Thutmose II, who in turn was succeeded by Thutmose II’s sister, Hatshepsut.

During his reign, the borders of Egypt’s empire reached their greatest expanse, extending in the north to Carchemish on the Euphrates and in the south up to Kurgus beyond the fourth cataract.

The scattered tribes of Apiru goat-rustlers in Canaan ran away from his armies but he subjected the towns and cities to his rule.

Thutmose II was the fourth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, and his reign is thought to be 13 years 1493 to 1479 BC (Low Chronology) or just only 3 years from around 1482 to 1479 BC. Little is known about him and he is overshadowed by his father Thutmose I, half-sister and wife Hatshepsut, and son Thutmose III. He died before the age of 30 and a body believed to be his was found in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

The dynasty next was led by Thutmose II (1493 – 1479 BC) and his queen, Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BC).

Hatshepsut[a] (/hɑːtˈʃɛpsʊt/ haht-SHEPP-sut; c. 1507–1458 BC) was the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II and the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from c. 1479 BC until c. 1458 BC (Low Chronology). She was Egypt’s second confirmed woman who ruled in her own right, the first being Sobekneferu/Nefrusobek in the Twelfth Dynasty.

She was the daughter of Thutmose I and soon after her husband’s death, ruled for over twenty years after becoming pharaoh during the minority of her stepson, who later would become pharaoh Thutmose III.

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. Officially he ruled Egypt from 28 April 1479 BC until 11 March 1425 BC, commencing with his coronation at the age of two and concluding with his death, aged fifty-six; however, during the first 22 years of his reign, he was coregent with his stepmother and aunt, Hatshepsut, who was named the pharaoh. While he was depicted as the first on surviving monuments, both were assigned the usual royal names and insignia and neither is given any obvious seniority over the other. Thutmose served as commander of Hatshepsut’s armies. During the final two years of his reign after the death of his firstborn son and heir Amenemhat, he appointed his son and successor Amenhotep II as junior co-regent.

Hatshepsut re-established international trade, restored the wealth of the country, fostered large building projects and created architectural advances that would not be rivaled for another thousand years when Greece and Rome stepped onto the world stage.

She restored the temples which were still in decay after the ravages of the Hyksos occupation.

Thutmose III (1458-1425 BC) who later became known as the greatest military pharaoh ever, also had a lengthy reign.

He had a second co-regency in his old age with his son by a minor wife who would become Amenhotep II.

Amenhotep II (sometimes called Amenophis II and meaning “Amun is Satisfied”) was the seventh pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. He inherited a vast kingdom from his father Thutmose III and held it by means of a few military campaigns in Syria; however, he fought much less than his father, and his reign saw the effective cessation of hostilities between Egypt and Mitanni, the major kingdoms vying for power in Syria. His reign is usually dated from 1427 to 1401 BC. His consort was Tiaa, who was barred from any prestige until Amenhotep’s son, Thutmose IV, came into power.

Amenhotep II (1427-1401 BC) was succeeded by Thutmose IV (1401-1391 BC),

Thutmose IV (sometimes read as Thutmosis or Tuthmosis IV, Thothmes in older history works in Latinized Greek; Ancient Egyptian: ḏḥwti.msi(.w) “Thoth is born”) was the 8th Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled in approximately the 14th century BC. His prenomen or royal name, Menkheperure, means “Established in forms is Re.” He was the son of Amenhotep II and Tiaa. Thutmose IV was the grandfather of Akhenaten.

who in his turn was followed by his son Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC) who was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Amenhotep III (Ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp(.w) Amānəḥūtpū, IPA: [ʔaˌmaːnəʔˈħutpu]; “Amun is satisfied”), also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent or Amenhotep the Great and Hellenized as Amenophis III, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different authors following the “Low Chronology”, he ruled Egypt from June 1386 to 1349 BC, or from June 1388 BC to December 1351 BC/1350 BC, after his father Thutmose IV died. Amenhotep was Thutmose’s son by a minor wife, Mutemwiya. His reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and splendour, when Egypt reached the peak of its artistic and international power, and as such he is considered one of ancient Egypt’s greatest pharaohs. When he died in the 38th or 39th year of his reign he was succeeded by his son Amenhotep IV, who later changed his name to Akhenaten.

The reigns of these two kings, which lasted some 50 years in total, are generally seen as a single phase.

At this time a peace was reached with Mittani, Egypt’s main adversary in Asia.

Amenhotep III undertook large scale building programs, the extent of which can only be compared with those of the much longer reign of Ramesses II later during the 19th dynasty.

Ramesses II[a] (/ˈræməsiːz, ˈræmsiːz, ˈræmziːz/; Ancient Egyptian: rꜥ-ms-sw, Rīꜥa-masē-Ancient Egyptian pronunciation: [ɾiːʕamaˈseːsə]; c. 1303 BC – 1213 BC), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Along with Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty, he is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom, which itself was the most powerful period of ancient Egypt. He is also widely considered one of ancient Egypt’s most successful warrior pharaohs, conducting no fewer than 15 military campaigns, all resulting in victories, excluding the Battle of Kadesh, generally considered a stalemate

It should be noted that the lengthy reign of Amenhotep III was a period of unprecedented prosperity and artistic splendor when Egypt reached the peak of her artistic and international power.

A 2008 list compiled by Forbes magazine found Amenhotep III to be the twelfth richest person in human history with a net worth of $155 billion in 2007 dollars.

When he died (probably in the 39th year of his reign), his son reigned as Amenhotep IV, later changing his royal name to Akhenaten (1353-1336 BC).

Akhenaten (pronounced /ˌækəˈnɑːtən/ listenⓘ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy, pronounced [ˈʔuːχəʔ nə ˈjaːtəj] ⓘ, meaning ‘Effective for the Aten’), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336[3] or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV (Ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp, meaning “Amun is satisfied”, Hellenized as Amenophis IV).

Akhenaten, who ruled for 17 years, was the famous “heretic Pharaoh” who (with his wife, Nefertiti) instituted what many identify as the first recorded monotheistic state religion.

Nefertiti (/ˌnɛfərˈtiːti/) (c. 1370 – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted the earliest known form of monotheism, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history. After her husband’s death, some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as the female pharaoh known by the throne name, Neferneferuaten and before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate. If Nefertiti did rule as pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes. In the 20th century, Nefertiti was made famous by the discovery and display of her ancient bust, now in Berlin’s Neues Museum. The bust is one of the most copied works of the art of ancient Egypt. It is attributed to the Egyptian sculptor Thutmose and was excavated from his buried studio complex in the early 20th century.

It was during the reign of Akhenaten and his super-wealthy father that the Amarna letters were written.

These cuneiform tablets have given us an important window into the events in Canaan with the rampaging Apiru thieves.

Following Akhenaten, Egypt was ruled by the boy king, Tutankhamun (1333 BC– 1324 BC).

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (Ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn; c. 1341 BC – c. 1323 BC), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled c. 1332 – 1323 BC during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he was likely a son of Akhenaten, thought to be the KV55 mummy. His mother was identified through DNA testing as The Younger Lady buried in KV35; she was a full sister of her husband.

SCIENCE: TECHNOLOGY: MODERN PAST: Tutankhamun’s Stargate – Library of Rickandria

His intact royal tomb was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 and gives an amazing example of the splendors and richness of Egypt during those times even though his tomb is certainly of minor importance compared to the greater pharaohs whose wealth-ladened tombs disappeared at the hands of tomb robbers.

Howard Carter (9 May 1874 – 2 March 1939) was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

Ay was the penultimate pharaoh of ancient Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. He held the throne of Egypt for a brief four-year period in the late 14th century BC. Prior to his rule, he was a close advisor to two, and perhaps three, other pharaohs of the dynasty. It is speculated that he was the power behind the throne during child ruler Tutankhamun’s reign, although there is no evidence for this aside from Tutankhamun’s youthfulness. His prenomen Kheperkheperure means “Everlasting are the Manifestations of Ra”, while his nomen Ay it-netjer reads as “Ay, Father of the God”. Records and monuments that can be clearly attributed to Ay are rare, both because his reign was short and because his successor, Horemheb, instigated a campaign of damnatio memoriae against him and the other pharaohs associated with the unpopular Amarna Period.

The last two members of the eighteenth dynasty – Ay and Horemheb – were followed by Ramesses I, who ascended the throne in 1292 BC and was the first pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Horemheb, also spelled Horemhab, Haremheb or Haremhab (Ancient Egyptian: ḥr-m-ḥb, meaning “Horus is in Jubilation”), was the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (1550–1292 BC). He ruled for at least 14 years between 1319 BC and 1292 BC. He had no relation to the preceding royal family other than by marriage to Mutnedjmet, who is thought (though disputed) to have been the daughter of his predecessor, Ay; he is believed to have been of common birth.

While these Pharaohs were ruling their empires and protecting their people, the goat-rustling Hyksos who had escaped Egypt, were scampering around:

- Sinai

- Canaan

- Syria

looking for weak towns to rob and fools to lend money to.

We left them counting their loot in the previous chapter while we followed the great empires of Babylonia and Assyria to their respective and historical demise.

And now, knowing how both Assyria and Babylonia met their ends, and which Pharaohs ruled after the Hyksos expulsion, let’s see what happened to the Hyksos.

By the time Pharaoh Ahmose allowed the Hyksos to escape in 1550 BC, Sumeria had by this time become a forgotten legend while its cuneiform writing, its culture, its inventions and its religious systems had been appropriated and absorbed by the Babylonians and Assyrians as well as by all of the other peoples who came to live in Mesopotamia.

However, even after 1800 years, the Sumerian Swindle, itself, remained the sole secret of the Babylonian and Assyrian tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders].

They were making themselves huge fortunes with this ancient scam just as the modern-day bankers and financiers do to this very day, swindling the people around them secretly, while pretending to be honest businessmen doing business as:

“it has always been.”

While the great empires of:

- Babylonia

- Assyria

- Egypt

contended with one another across the centuries, the:

- Gutians

- Hittites

- Hurrians

- Scythians

- Medes

- Amorites

- Kassites

- Sea Peoples

and numerous other tribal and ethnic confederations walked on foot and rode on donkeys and horses and chariots back and forth across the dusty plains of the Fertile Crescent and among the hills of Palestine and Anatolia.

They vied with one another over:

- water rights

- farmlands

- trade goods

and silver, combined with the violent arguments between the Type-A personalities and the charismatic psychopaths who had become their kings.

SPIRITUALITY: EMPATHY: TOXICITY: Traits of a Psychopath – Library of Rickandria

These historic struggles for empire were vast in scale and filled with incredible suffering and bloodshed.

But in Palestine, though the struggles were no less lethal man-to-man, they were certainly quite small and insignificant when set beside the epic scale of the marching armies of the great empires.

- Egypt

- Hattiland

- Mitanni

- Assyria

and Babylonia were truly enormous while the petty kingdoms in:

- Canaan

- Moab

- Judea

were truly tiny.

As the great empires traded on an international scale and fought wars involving tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of people, the small towns and villages of Palestine fought battles with ten or even a hundred goat-herders wielding bronze swords and copper maces and throwing rocks with their slings.

Every town and village had to protect its farming and grazing lands from the roving bandits and cattle rustlers who infested the countryside.

These areas of Canaan were too insignificant and too far away from the power centers of:

- Mesopotamia

- Anatolia

- Egypt

for these small towns to ask the Great Powers for protection from the small bands of rampaging Apiru.

But Palestine had major trade routes running through it from Arabia connecting:

- Egypt

- Anatolia

- Mesopotamia

and the Mediterranean, so it had strategic importance to the great empires.

Yet, the land was sprinkled with small villages and tiny towns.

It was a quandary.

To guard such an area was more of an inconvenience than a profitable tactic for the great empires.

But because of the convergence of trade routes, this mostly desolate land was never-the-less strategically important.

Now, back again to 1550 BC.

Once Pharaoh Ahmose began his assault from Upper Egypt, those Hyksos who could do so commandeered:

- boats

- horses

- chariots

and donkeys and ran for their lives.

These were the commanders of the Hyksos, the leading generals and lieutenants, the wealthier tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders] and their families and bodyguards, plantation overseerers, boat-owners and their families.

All of these upper classes fled north along the Nile to the safety of Avaris.

But the lower-level Hyksos who had been ignorant shepherds before the Hyksos takeover and who were members of the gangs of enforcers and bosses over the enslaved Egyptian farmers, were left behind to fend for themselves.

Because there was no room on the boats and not enough horses and donkeys, these lower-class shepherds were abandoned to their fate.

As the hired hands of Hyksos slavedrivers, they had murdered and enslaved the Egyptians and had helped to loot the temples and plunder the tombs

So, when the Egyptian army caught up with them, they were either killed or bound in fetters and themselves enslaved.

For now, let’s leave these enslaved Hyksos (Apiru) chained up in Egypt, working for the Egyptians who were none too happy with those formerly cruel and rapacious Hyksos shepherds and their families of thieves.

Their history is of little importance.

They were slaves.

Nothing more can be said about them that cannot be said about any other slaves of the ancient Near East.

They worked for the Egyptian people whom they had tortured and destroyed and looted.

So, slavery was their reward.

Although slaves were not allowed to work on Egyptian pyramids or temples since this was a holy privilege of the Egyptian people, alone, these Apiru slaves no doubt did the brick making and field plowing during their time when Pharaoh Ahmose built the last pyramid by an Egyptian monarch.

Illiterate, they had no way of writing down their travails.

And of what history of slaves can there be other than the daily drudgery of labor?

They and their descendants were to remain as slaves in Egypt until they were released from bondage by Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 671 BC.

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian Akkadian: 𒀸𒋩𒆕𒀀, romanized: Aššur-bāni-apli, meaning “Ashur is the creator of the heir”) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the throne as the favored heir of his father Esarhaddon; his 38-year reign was among the longest of any Assyrian king. Though sometimes regarded as the apogee of ancient Assyria, his reign also marked the last time Assyrian armies waged war throughout the ancient Near East and the beginning of the end of Assyrian dominion over the region.

We will pick up their history more thoroughly in Volume Two, The Monsters of Babylon.

So, leaving them at their labors, let’s move on to the second group of escapees from the wrath of the Egyptians.

Those Hyksos who had reached Avarice in time to find safety there, can be divided into the other three groups.

As previously stated, Pharaoh Ahmose had allowed the Hyksos to leave Avarice and take with them all of their loot as a way of avoiding a long siege.

When the Egyptians let them go, some of the Hyksos turned to the east and south and wandered with their loot and small cattle into the Sinai region of Arabia.

Nabonidus (Babylonian cuneiform: Nabû-naʾid, meaning “May Nabu be exalted” or “Nabu is praised”) was the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 556 BC to the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenian Empire under Cyrus the Great in 539 BC. Nabonidus was the last native ruler of ancient Mesopotamia, the end of his reign marking the end of thousands of years of Sumero-Akkadian states, kingdoms and empires. He was also the last independent king of Babylon. Regarded as one of the most vibrant and individualistic rulers of his time, Nabonidus is characterised by some scholars as an unorthodox religious reformer and as the first archaeologist.

This desolate region king Nabonidus would later name after his Moon God, Sin, as the “Wilderness of Sin,” that is, “Sinai.”

Sin (/ˈsiːn/) or Suen (Akkadian: 𒀭𒂗𒍪, dEN.ZU[1]) also known as Nanna (Sumerian: 𒀭𒋀𒆠 DŠEŠ.KI, DNANNA) is the Mesopotamian god representing the moon. While these two names originate in two different languages, respectively Akkadian and Sumerian, they were already used interchangeably to refer to one deity in the Early Dynastic period.

Some of them got lost in the desert wilderness of Sinai where for forty years they herded their goats and ate grasshoppers before finding their way back into Canaan.

Schlepping their gold and silver ornaments and herding their goats, some of them wandered into the moderately-settled hill country of Canaan where they took up once again their goat rustling and raiding.

No doubt these illiterate goat-rustlers were extremely pleased with their good luck.

Pharaoh Ahmose had allowed them to escape from Egypt and take with them whatever loot that they already possessed.

They had been the foot-soldiers of the Hyksos invasion.

They, as well as their poorer relatives who had been captured and enslaved by the Egyptians, were the pawns of the operation, totally expendable and useful for basic soldiering and gangster work.

They had entered Egypt as shepherds and bandits, and they left Egypt following that same pastoral life as their forefathers and fathers.

Only now, they were rich gangs of dusty goat-herders carrying an unusually large amount of Egyptian gold and silver and fine linens and ebony furniture and expensive incense and gemstones into the uninhabited regions of Sinai.

True to their nature, these tribes began lurking around Palestine as wandering bands of thieves and goat-rustlers.

They had plenty of silver and gold and goats and cattle but no land of their own.

The quiet towns and villages of the region could eke out a living in the rocky and dry land, but the land could not support both the Apiru and the Canaanites.

Besides, the Apiru were thieves.

They were not wanted in Egypt by the Egyptians, and they certainly were not welcome in Canaan by the coastal cities or by the poor inland villages.

Yet, when did thieves ever worry about whether they were welcome or not since they never were?

As wandering nomads, traveling on foot and by donkey, there was not much space on their pack animals and carts for them to be carrying around statues of their gods.

No different than any other of the people of the ancient Near East in their belief system, the Apiru believed in many gods, and they believed that each god lived in his own territory.

As previously mentioned, their fortress city of Avarice had been home to religions from all over the ancient Near East.

- Canaanite-style temples

- Minoan wall paintings

- Palestinian-type burials

all made use of statues of gods in their religious services.

In Egypt, they had worshipped the Egyptian gods in whose territory they had invaded, most notably the Egyptian Moon God, Yah.

Iah (Ancient Egyptian: jꜥḥ; 𓇋𓂝𓎛𓇹, Coptic ⲟⲟϩ) is a lunar deity in ancient Egyptian religion. The word jꜥḥ simply means “Moon”. It is also transcribed as Yah, Jah, Aa, or Aah.

The Moon God was always a favorite of the Semites.

He was called:

- Sin in Babylonia

- Lah in Arabia

- Yah in Egypt

The Hyksos pharaoh had had the Egyptian priests serving him at court, calling upon the power of Egyptian gods for the protection of the Hyksos.

So, praying to Yah was a practice learned from their residence in Egypt.

They had been chased out of Egypt by Pharaoh Ahmose (Yahmose) whose name meant “The Moon is Born”.

So, all of this influence of moon worship carried over to the worship of their Moon God, Yahweh, or “Yah is here”.

RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY: YHVH: The Truth About “Yahweh/Jehovah” – Library of Rickandria

But once they were back wandering in the wilderness looking for water and forage, some of these Apiru returned to the worship of their goat herder gods.

After all, the gods were believed to take up residence at specific geographical locations and to live in specific city temples.

Among the hills and mountains of the Sinai Peninsula, the Apiru worshipped El-Shaddai, the god of the mountain.

In these hot and arid lands, the work of this god could be seen in the clouds that surrounded the highest mountain tops as thunder and lightning.

This mighty god of flashes of burning fire, caused the goats and sheep to panic and the women to scream.

This was not a god to be trifled with.

Whenever they needed additional protection, their priests and elders would go up into those mountains to seek out this god and to offer him sacrifices atop piles of heaped stones sprinkled with the blood of their goats and sheep.

The god of the mountain, El-Shaddai, was not only a mighty god of thunderings and earthquakes but he was also invisible.

And for people living in goat-hair tents and riding donkeys, invisible gods didn’t weigh very much.

This god could only be seen dressed in his surrounding clouds and lightning bolts high up on the mountaintops or as pillars of whirling dust devils that surrounded the goat-rustlers as they traversed the deserts.

Since their invisible god didn’t weigh anything, they didn’t need statues or idols to pray to him, which was convenient because that left more room on their pack donkeys for loot.

The Sinai desert was important for its copper and gemstone mines and its trade routes that passed through Arabia and to the Horn of Africa as well as from the Gulf of Aqaba over the Red Sea to:

- Punt

- India

- Elam

and Babylonia.

But these Apiru cared nothing about that.

Once these Hyksos herdsmen had escaped into the wilderness, they had thousands of square miles to roam in.

For many years, they spent their days searching out oasis and forage for their animals.

And, when their children would ask:

“Where did these gold Egyptian bracelets come from?”

they did not want to tell their children of running for their lives in defeat.

So, they told stories around the campfires about how they and their forefathers had out-foxed Pharaoh and had stolen the jewelry of the Egyptians.

Through the generations and the illusion of their asl, the stories transmogrified into:

“we outfoxed the Egyptians.”

After chasing the Hyksos out of Egypt, Pharaoh Ahmose and his successors of the Eighteenth Dynasty treated all of Canaan and Sinai as a buffer against the empires of the Hittites and Babylonians.

The Egyptians had been insular and self-absorbed before the Hyksos invasion, relying upon the protection of their surrounding deserts.

But they had learned the hard lesson of international politics.

And that lesson is, if you do not defend your country, you will lose it to foreigners.

The fleeing tribes of Hyksos bandits and scattered families of shepherds were of less concern for a mighty king of Egypt than were the powerful empires across his borders.

And so, after warfare had extended the influence of Egypt all the way into Syria, eventually, with the ensuing peace, the Egyptian and Babylonian royal families became linked through the diplomacy of marriage.

This diplomacy was recorded on the clay Amarna tablets written in cuneiform which had been deposited in the royal archives of Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC) and his son, Akhenaton (1353 1336 BC).

They were written about 200 years after the Hyksos had been expelled.

Some of those letters were written by the kings of Hattiland and Babyonia to the Pharaohs.

But most of these letters were written to Pharaoh by Canaanite princes in Palestine, Phoenicia and Southern Syria during the early fourteenth century BC.

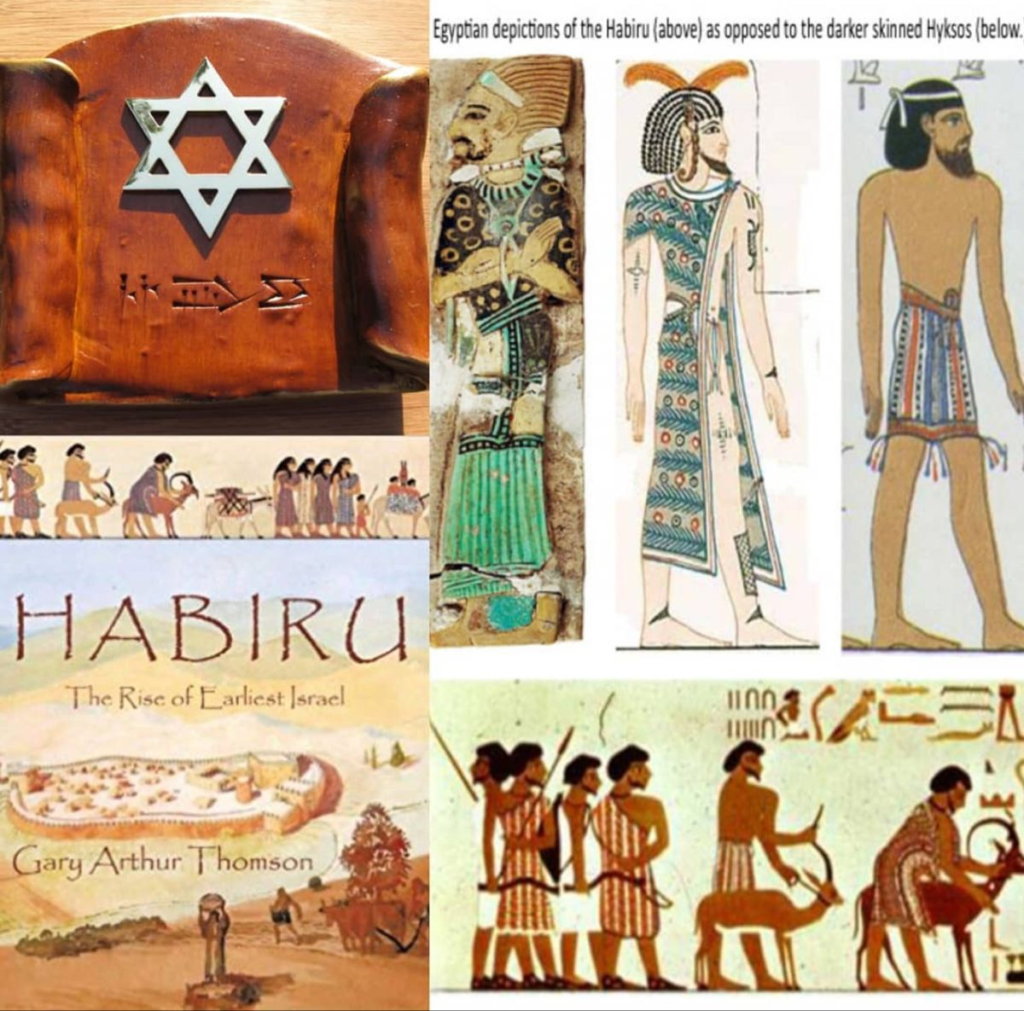

These letters tell of attacks by the bandits known as “Apiru” or “Hapiru” or “Habiru” or “Hebrew”.

A portion of this royal correspondence between:

- Egypt

- Babylonia

- the Hittites

was first discovered by French archeologists at Mari on the Euphrates.

Another group of letters comes from the half century around 1400 BC and was found in central Egypt at El Amarna.

These Amarna Letters make it abundantly clear that Babylonian influence in the development of international law was so pre-eminent that Akkadian had become the principal language of diplomacy between rulers even where, as between Egypt and the Hittites, it was the mother tongue of neither party. [292]

In other words, the language and the writing of the tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders] of:

- Babylonia

- Assyria

- Hattiland

was the standard language of the civilized world.

The moneylenders could do business with every empire in the ancient Near East using the Akkadian language and cuneiform writing.

In the Amarna letters, the kings addressed each other as “brother”, a greeting implying equality of status.

Gifts were exchanged –

- horses

- chariots

- lapis lazuli

from Babylon for gold from Egypt, and also:

- silver

- bronze

- ivory

furniture of ebony and other precious:

- woods

- garments

- fine oil

Teams of horses were much in demand from the Kassites, who were noted not only for their horsemanship but also for their horses.

Kadašman-Enlil II, typically rendered dka-dáš-man-dEN.LÍL[nb 1] in contemporary inscriptions, meaning “he believes in Enlil” (c. 1263-1255 BC) was the 25th king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty of Babylon.

In a letter to Kadashman-Enlil II, the Hittite king Hattusili III remarks that in Babylonia:

“there are more horses even than straw”

and, despite the fact that the well-watered Hittite homeland would seem more suited to the breeding of horses than the dry plains of Babylonia, he demanded “fine horses” from Babylon.

The general tone of the Amarna letters between Babylonia and Egypt suggests a decline in relations between the two countries, possibly a reflection of growing weakness in Egypt under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten.

Both of these Pharaohs had plenty of wealth to rule their empire but neither had the will to do so.

Kadašman-Enlil I (mka-dáš-man-dEN.LÍL in contemporary inscriptions) was a Kassite King of Babylon from ca. 1374 BC to 1360 BC, perhaps the 18th of the dynasty.

Both Kadashman-Enlil I and Burna-burias complain of the ill-treatment of their messengers and the stinginess of Pharaoh.

Burna-Buriaš II was a Kassite king of Karduniaš (Babylon) in the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1359–1333 BC, where the Short and Middle chronologies have converged. The proverb “the time of checking the books is the shepherds’ ordeal” was attributed to him in a letter to the later king Esarhaddon from his agent Mar-Issar.

“Twenty minas of gold”

sent to Burna-burias from Egypt:

“were not complete, for when they were put in the furnace, five minas did not come forth.”

In the letter to Akhenaten, Burna-burias asks that Pharaoh seal and dispatch the gold himself and not leave this task to some “trustworthy official”. [293]

Although the kings of:

- Babylonia

- Hattiland

- Egypt

contented themselves with personal gifts and concubines, the tone of the Amarna Letters from the various governors of Canaan were very different.

There, the lands were being overrun by Hebrew bandits.

It is clear from these desperate pleas for help that the Hebrews (the Apiru) were taking over the entire region and Pharaoh was doing nothing to protect his land.

As you read the Amarna Letters, it is easy to see the close correlation between them and the Old Testament stories of how the Hebrews attacked and took over Canaan.

The events in these letters took place about two hundred years after the Hyksos had escaped from Egypt.

So, as their circumcised and promiscuous population increased, these Hebrew bandits were becoming an increasing source of trouble to the people of the entire region, just as they are in the present day.

Please understand that these Hebrews were not Jews because there were no Jews anywhere in the world at that time.

They were merely the scattered tribes of Hyksos bandits.

The Egyptians called them Apiru because that was the name for their slaves and peasant laborers.

To the Canaanites, since the Apiru were “cut throats” and “bandits” and “thieves,” then that is what the Egyptian word meant to the Canaanites —

- goat rustlers

- bandits

- thieves

Labaya, the governor of Shechem, was a Canaanite.

The Amarna Letters show that although he was supposed to have been a loyal subject of Pharaoh Akhenaten, in fact, he was secretly a Hebrew.

With the usual Semitic deceit, he claimed to be loyal to Pharaoh while simultaneously raiding the caravans and the territories of his neighbors on all sides.

Milkilu, the governor of Gezer, seems to have also been in league with the Hebrews.

As the looters of Egypt, these Hebrew bandits were now turning their attention upon the towns and villages of Canaan.

Two hundred years had passed since they had been chased out of Egypt.

With their many wives producing a multitude of children, their numbers had increased enough that they could challenge the established regime.

The Amarna Letters describe the situation.

In one letter, Labaya, the Canaanite prince of Shechem in the central hill country, [294] hypocritically complains to Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC) that he is loyal and is being slandered by the other princes.

Furthermore,

“I did not know that my son associates with the Apiru, and I have verily delivered him into the hand of Addaya.” [295]

Thus, the Hebrew bandits were not merely tribes related by blood and closed to outsiders but were actually open membership gangs which outsiders could join and become full members participating in their raids.

But Labaya’s protestations of innocence certainly did not fool his neighbors who had to defend themselves from his depredations.

Biridya, prince of Meggido, writes to Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC) of the troubles he is having capturing the bandit prince Labaya.

Biridiya was the ruler of Megiddo, northern part of the southern Levant, in the 14th century BC. At the time Megiddo was a city-state submitting to the Egyptian Empire. He is part of the intrigues surrounding the rebel Labaya of Shechem.

That these letters were dictated to a scribe is shown in the phrase, “Let Pharaoh know”:

“Let Pharaoh know that ever since the archers returned to Egypt, Labaya has carried on hostilities against me, and we are not able to pluck the wool, and we are not able to go outside the gate in the presence of Labaya, since he learned that thou hast not given archers.

And now his face is set to take Megiddo, but let Pharaoh protect his city lest Labaya seize it.

Verily, the city is destroyed by death from pestilence and disease.

Let Pharaoh give one hundred garrison troops to guard the city lest Labaya seize it.

Verily, there is no other purpose in Labaya.

He seeks to destroy Megiddo.”

And Biridya continues on another tablet,

“I said to my brethren, ‘If the gods of Pharaoh, our lord, grant that we capture Labaya, then we will bring him alive to Pharaoh, our lord.’

But my mare was felled by an arrow, and I alighted afterwards and rode with Yashdata.

But before my arrival, they had slain Labaya.” [296]

In another letter, Milkilu, the prince of Gezer, pleads with Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC) and begs Pharaoh for some help against the rampaging Hebrew thieves.

He writes on behalf of himself and his friend, Shuwardata, prince of Hebron and says:

“Let Pharaoh know that powerful is the hostility against me and against Shuwardata.

Let Pharaoh, my lord, protect his land from the hand of the Apiru.

If not, then let Pharaoh, my lord, send chariots to fetch us, lest our servants smite us.” [297]

Thus, it can be seen that the fighting throughout the area was so intense that Milkilu wanted to retreat to Egypt.

The Hebrews were attacking the entire region.

Under the aging Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1388-1350 BC), Egypt was rich but neglectfully weak and unresponsive.

This old Pharaoh Amenhotep III replied in a letter to Milkilu, giving insight of the Pharaoh’s interest in his Canaanite territories and the trade goods of the day.

Remember that Amenhotep III was the richest king in Egyptian history.

That he was enjoying his wealth and was not at all concerned about the fate of his Canaanite possessions, his reply makes quite clear:

“To Milkilu (1350-1335 BC), prince of Gezer.

Thus, Pharaoh says.

Now I have sent thee this tablet to say to thee: behold, I am sending to thee Hanya, the commissioner of the archers, together with goods, in order to procure fine concubines and weaving women: silver, gold, linen garments, turquoise, all sorts of precious stones, chairs of ebony, as well as every good thing, totaling 160 deben.

Total: 40 concubines.

The price of each concubine is 40 shekels of silver.

So, send very fine concubines in whom there is no blemish.

And let Pharaoh, thy lord, say to thee,

‘This is good.

To thee life has been decreed.’

And mayest thou know that Pharaoh is well, like the Sun-god.

His troops, his chariots, his horses are very well.

Behold, the god Amon has placed the upper land, the lower land, the rising of the sun, and the setting of the sun under the two feet of Pharaoh.” [298]

This letter also shows the mystic power that was assumed both by Pharaoh and his subjects where-by he could presume in a god-like way,

“To thee life has been decreed.”

Obviously, getting concubines for his harem was of more importance to this lecherous, old and wealthy Pharaoh than protecting his lands from the Hebrew bandits.

But more than god-like decrees of Pharaoh were needed to stop the bandits.

The Hebrews used the captured towns as fortresses and staging areas for further raids.

After Amenhotep III died, the new Pharaoh was not anymore helpful to these besieged governors.

The new Pharaoh was Akhenaton (1353-1336 BC) who had inherited all of the wealth of his father but whose main interest was in the Sun God religion that he founded.

Akhenaton was the famous Pharaoh who established the world’s first monotheistic religion 800 years before there were any Jews to lie about doing it first.

At the beginning of Akhenaten’s reign, Shuwardata wrote:

“Let Pharaoh, my lord, learn that the chief of the Apiru has risen in arms against the lands which the god of Pharaoh, my lord, gave me; but I have smitten him.

Also let Pharaoh, my lord, know that all my brethren have abandoned me, and it is I and Abdu-Heba (governor of Jerusalem) who fight against the chief of the Apiru.

And Zurata, prince of Accho, and Indarapatra, prince of Achshaph, it was they who hastened with fifty chariots to my help – for I had been robbed by the Apiru – but behold, they are fighting against me, so let it be agreeable to Pharaoh, my lord, and let him send Tanhamu, and let us make war in earnest, and let the lands of Pharaoh, my lord, be restored to their former limits!” [299]

Under a weak and unresponsive Pharaoh Akhenaton, not only were the Hebrews attacking the towns of Canaan without fear of retribution, but many of these towns were actually joining the Hebrew gangs.

The loyalty to the Pharaoh was quickly being replaced with self-interest and the opportunity for acquiring land and loot.

The Hebrews were so numerous that even the two foes, Abdi-Heba governor of Jerusalem and Shuwardata of Hebron, could not fight against them.

Abdi-Ḫeba (Abdi-Kheba, Abdi-Ḫepat, or Abdi-Ḫebat) was a local chieftain of Jerusalem during the Amarna period (mid-1330s BC). Egyptian documents have him deny he was a mayor (ḫazānu) and assert he is a soldier (we’w), the implication being he was the son of a local chief sent to Egypt to receive military training there.

In this letter, Shuwardata complains to Pharaoh Akhenaten that Abdi-Heba, the prince of Jerusalem, was one of the land-grabbers:

“Pharaoh, my lord, sent me to make war against Keilah.

I have made war, and I was successful; my town has been restored to me.

Why did Abdi-Heba (Prince of Jerusalem) write to the people of Keilah saying,

‘Take my silver and follow me”?

Let Pharaoh, my lord, know that Abdu-Heba had taken the town from my hand.

Further, let Pharaoh, my lord, investigate; if I have taken a man or a single ox or an ass from him, then he is in the right!

Further Labaya is dead, who seized our towns; but behold, Abdi-Heba is another Labaya, and he also seizes our towns!

So let Pharaoh take thought for his servant because of this deed!

And I will not do anything until the king sends back a message to his servant.” [300]

The territorial infighting between the governors and princes of Canaan was always superseded by the general chaos of the entire region brought on by the thieving Hebrew tribes.

Abdi-Heba’s name can be translated as “servant of Hebat”, a Hurrian goddess.

Ḫepat (Hurrian: 𒀭𒄭𒁁, dḫe-pát; also romanized as Ḫebat; Ugaritic 𐎃𐎁𐎚, ḫbt) was a goddess associated with Aleppo, originally worshiped in the north of modern Syria in the third millennium BCE.

The entire populace of pre-Israelite Jerusalem (known as Jebusites in the Bible) was under the ban of the Hebrew god who demanded their complete genocide.

NEW WORLD ORDER: Genocide IS & Always Has Been a Jewish Ideal – Library of Rickandria

In this letter, Abdi-Heba complained to Pharaoh Akhenaten:

“Lost are the lands of Pharaoh!

Do you not hearken unto me?

All the governors are lost; Pharaoh, my lord, does not have a single governor left!

Let Pharaoh turn his attention to the archers and let Pharaoh, my lord, send out troops of archers, for Pharaoh has no lands left!

The Apiru plunder all the lands of Pharaoh.

If there are archers here in this year, the lands of Pharaoh, my lord, will remain intact; but if there are no archers here the lands of Pharaoh, my lord, will be lost!” [301]

The entire region was in turmoil.

The Hebrews were turning Canaan into a total war zone with their raids and plundering.

Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem complains about a number of events which recur in other letters.

In the first place, he excoriates Milkilu of Gezer and Tagu of the northern Coastal Plain of Palestine for their aggression against Rubutu, which lay somewhere in the region southwest of Megiddo and Taanach.

In the second place, he urges Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BC) to instruct his officers to supply the Egyptian archers from the towns in the plain of Sharon in order to avert heavy drain on the scanty supplies of Jerusalem.

He finally complains that his last caravan containing tribute and captives for Pharaoh was attacked and robbed near Ajalon, presumably by the men of Milkilu of Gezer and the sons of Labaya. [302]

Although Akhenaten had sent a troop of Nubian archers to aid Abdi-Heba, they were certainly not a blessing.

Much like their modern-day descendants who take every pretext and opportunity to riot and loot, the black Nubian mercenaries garrisoned in Jerusalem by Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BC) had been caught up in the riotous pillaging of the time and had even attacked the governor, Abdi-Heba, himself, as they attempted to burglarize his home.

In another letter to Akhenaten, Abdi-Heba wrote:

“Behold, this deed is the deed of Milkilu and the deed of the sons of Labaya who have given the land of Pharaoh to the Apiru.

Behold, O Pharaoh, my lord, I am right! With reference to the Nubians, let my king ask the commissioners whether my house is not very strong!

Yet, they attempted a very great crime; they took their implements and breached the roof….

The men of the land of Nubia have committed an evil deed against me.

I was almost killed by the men of the land of Nubia in my own house.

Let Pharaoh call them to account. Seven times and seven times let Pharaoh, my lord, avenge me!” [303]

As the general banditry and attacks by the Hebrews spread, Abdi-Heba, governor of Jerusalem, sent yet another letter to the unresponsive Pharaoh Akhenaten:

“Let Pharaoh take thought of his land! The land of Pharaoh is lost; in its entirety it is taken from me; there is war against me, as far as the lands of Seir and as far as Gath-carmel!

All the governors are at peace, but there is war against me.

I have become like an Apiru and do not see the two eyes of Pharaoh, my lord, for there is war against me. I have become like a ship in the midst of the sea!

The arm of the mighty Pharaoh conquers the land of Naharaim and the land of Cush, but now the Apiru capture the cities of Pharaoh.

There is not a single governor remaining to Pharaoh, my lord – all have perished.

Behold, Turbazu has been slain in the very gate of Sile, yet Pharaoh holds his peace.

Behold Zimreda, the townsmen of Lachish have smitten him, slaves who had become Apiru. Yaptih-Hadad has been slain in the very gate of Sile, yet Pharaoh holds his peace. Wherefore does not Pharaoh call them to account?” [304]

Thus, it is clear that Canaan was being over-run by the Hebrews.

This word, “Hebrew”, was not a religious term since this and other letters by the other governors indicate that anyone could join the Hebrew gangs, anyone could become a Hebrew (Apiru) gangster and goat-rustler.

They were not an exclusive group of religious nomads as the lying rabbis claim.

They were raiders who welcomed more allies to increase the size of their bandit tribes.

As Abdi-Heba laments,

“I have become like an Apiru (Hebrew) …. I have become like a ship in the midst of the sea.”

It is quite clear that these roving bandits, these Hebrews, who attacked from the desert regions, welcomed any who would rebel and join their tribes.

Whether they were sons of local kings like the son of Labaya or:

“slaves who had become Apiru”

like the townsmen of Lachish, all who could fight were welcome to join the Hebrew bandits in their:

- rape

- looting

- warfare

and genocide across all of Canaan.

Modern day apologists can argue that these Hebrews were so-called “freedom fighters” who were freeing Canaan from Egyptian domination.

But this argument ignores the fact that the Hebrews, themselves, were foreign raiders from the deserts, the wandering dregs of Hyksos from Egypt, who were in Canaan to get whatever they could steal.

In another letter, Abdi-Heba writes to Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353 1336 BC):

“Behold, Milkilu does not break his alliance with the sons of Labaya and with the sons of Arzayu, in order to covet the land of Pharaoh for themselves.

As for a governor who does such a deed as this, why does not Pharaoh call him to account?

Behold Milkilu and Tagu!

The deed which they have done is this, that they have taken it, the town of Rubutu.

And now as for Jerusalem – Behold this land belongs to Pharaoh or why like the town of Gaza is it loyal to Pharaoh?

Behold, the land of the town of Gath-carmel, it belongs to Tagu and the men of Gath have a garrison in Beth-Shan.

Or shall we do like Labaya, who gave the land of Shechem to the Apiru?

Milkilu has written to Tagu and the sons of Labaya saying, ‘You are members of my house. Yield all of their demands to the men of Keilah and let us break our alliance with Jerusalem!’” [305]

Later, Abdi-Heba wrote to Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353 1336 BC):

“Behold the deed which Milkilu and Shuwardata did to the land of Pharaoh!

They rushed troops of Gezer, troops of Gath and troops of Keilah; they took the land of Rubutu; the land of Pharaoh went over to the Apiru people.

But now even a town of the land of Jerusalem, Bethlehem by name, a town belonging to Pharaoh, has gone over to the side of the people of Keilah.

Let Pharaoh hearken to Abdi-Heba, thy servant, and let him send archers to recover the royal land for Pharaoh.

But if there are no archers, the land of Pharaoh will pass over to the Apiru people.” [306]

Balu-shipti, the prince of Gezer, wrote during the middle of Akhenaton’s reign (1353-1336 BC), following the death of Milkilu:

“Behold the deed of the Egyptian official Peya against Gezer.

How many days he plundered it so that it has become an empty cauldron because of him.

From the mountains, people are ransomed for thirty shekels of silver, but from Peya for one hundred shekels of silver, so know these words of thy servant!” [307]

Yapahu, the prince of Gezer, wrote to Akhenaten thus:

“Let Pharaoh know that my youngest brother is estranged from me, and has entered Muhhazu, and has given his two hands to the chief of the Apiru.

And now the land of Janna is hostile to me.

Have concern for thy land!” [308]

Such were the tumultuous times.

Once the Hyksos (Apiru) had been expelled from Egypt, they continued their thieving and plundering and were known by the Canaanite populace as “cut-throats”, “bandits”, “thieves”, or “Hebrews”.

And once they had increased their tribal numbers enough to become a military threat, they committed crimes wherever they roamed:

- killing

- thieving

- raping

- rustling

and taking over entire towns after first murdering the owners.

We know the names of those unfortunate governors of the Canaanite cities from their Amarna letters.

Most of those governors were Indo-Aryans:

- Biryawaza, prince of Damascus.

- Biridiya, prince of Megiddo.

- Zurata, prince of Acre.

- Mut-Balu, prince of Pella.

- Ayab, prince of Ashtaroth.

- Milkilu, prince of Gezer.

- Shuwardata, prince of the Hebron district.

And the long-suffering Abdu-Heba, governor of the small town of Urusalem (Jerusalem).

But their letters do not record the names of their enemies except as the general names of bandits or thieves or cut-throats which they called Apiru or Hapiru or Habiru or Hebrews.

They do not mention the tribal names of their Hebrew enemies – the tribes of:

and Gad.

For these names, we must read the Hebrew account of the “conquest of Canaan” in the Old Testament.

The full account of how the Hebrews genocided the Canaanites and stole their property is explained in its entirety in Volume Two: The Monsters of Babylon.

But for now, let’s leave the first and second groups of Hyksos and study the third group.

The first group of Hyksos were still enslaved in Egypt during these times, and they were called Apiru (slaves) by the Egyptians.

The second group of Hyksos who had escaped Egypt were ravaging the countryside of Canaan.

The princes of the cities in Canaan also called them by the Egyptian name when writing to Pharaoh.

But in this case, Apiru meant “bandit”.

The third group was composed of the Hyksos officials, their generals and military guards and some of the lower level tamkarum [merchant moneylenders].

For these administrators and leaders of the Hyksos, who had been involved in looting and administering Egypt, only life in the cities offered any allure to them.

The luxuries of:

- good food

- bawdy taverns

- slave women and prostitutes

and an easy life in a debauched Egypt, was something that they wanted to continue.

These mid-level and upper-level Hyksos knew how to lead and organize their men.

They had the loot that Pharaoh Ahmose had allowed them as well as the accumulation of over a hundred years of looting which their families had safely hoarded in the coastal cities of Canaan.

With such wealth and organizational skills, these tradesmen and merchants had no intention of going back to Babylonia where they could no longer be independent bankers and gangsters.

They had tasted wealth and power without being the servants of the kings or subalterns of the tamkarum trade guilds of Babylonia.

They had ruled Egypt as kings with wealth, power and prestige, while the mighty Egyptians had been forced to literally kiss their feet.

So, to once again become servants to a Babylonian king was not appealing to them.

Besides, the trade guild cities of Babylonia were distant, and the markets and trade routes were controlled by competitive tamkarum guilds.

For these particular Hyksos, the markets were either closed to them or tightly controlled by competing guilds, giving them secondary profits in Mesopotamia as mere employees of the tamkarum patriarchs.

However, there were richer possibilities, not in the distant markets of Babylonia and Assyria, but near at hand in the untapped markets of the Mediterranean Sea.

These new markets were scattered throughout the Mediterranean Sea on both the North African and European continents.

No one controlled these markets because these areas were lightly populated and few of those foreign merchants understood the power of organized, international trade cartels.

What was even better, none of those people in the new lands knew anything about the Sumerian Swindle.

These were markets with unsophisticated and illiterate peoples who were innocent of the deceits of the tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders].

So, this third group of Hyksos escaped from Egypt and schlepped their loot to the port cities of:

- Acre

- Tyre

- Sidon

and Byblos and began building ships.

In these fortified port cities, these Hyksos were safe from the raids and troubles that the Hebrew shepherds were causing throughout Canaan.

Their families and guilds had been among the original conspirators in the take-over of Egypt over a hundred years previously.

They had been the second-tier field agents for the merchant-moneylender guilds in Babylonia but not the main directors.

As:

- generals

- captains

- lieutenants

in the army, as high priests for the Canaanite gods, as merchants and traders, as sea captains for the Red Sea fleets, as caravan organizers and warehousemen, as an educated elite, they had been among the leading profiteers of the Hyksos invasion of Egypt.

But once they had been expelled by Pharaoh Ahmose, they were like grasping arms and hands that had been cut off from the head which was based in Babylonia.

During their years in Egypt, these Hyksos had developed trade partners along the Canaanite coastal cities and on Crete as well as in Babylonia.

So, when they were expelled, unlike the shepherd Hyksos wandering around as flea-bitten and unsophisticated Hebrew bandits, these merchant Hyksos had somewhere to go and trade partners with whom to do business.

The entire Mediterranean Sea and its margins was open to them.

They transferred the sailors and sea captains from among their ships in the Red Sea and based them in the cities along the Canaanite coast.

From the cities of:

- Dor

- Acre

- Tyre

- Sarepta

- Sidon

- Beritos

- Tripoli

and Arwad, these wealthy Hyksos began building a trading fleet that could carry the manufactured goods of:

- Egypt

- Assyria

- Syria

and Babylonia into the less-civilized lands of:

- Greece

- Europe

- North Africa

and the Black Sea.

All they needed were these seaports as a base of operations and some new ships and they were back in business.

Adhering to their basic business policy of dealing whenever possible in easily transported, rare and therefore expensive goods, these Hyksos [merchant moneylenders] had such an item readily at hand with which to sell at a high profit and with which to bribe the kings of any country.

And best of all, as in Secret Fraud #7 of the Sumerian Swindle, it could be monopolized.

This product was the famous purple dye that was not only very beautiful but very costly.

This dye was made from the sea snails of the eastern Mediterranean coast found in the very area where the Hyksos established their new trading ports.

By monopolizing the manufacture of this dye, the Hyksos merchant-moneylenders had an immediate source of profit which they, alone, could control.

The purple dye was manufactured from a medium sized predatory sea snail that thrived in the area.

The snails were crushed to extract the dye.

It took twelve thousand snails to yield 1.4 grams of pure dye, enough to color only the trim of a single garment.

So, purple dye was very, very expensive.

The expense rendered purple-dyed textiles as status symbols and became a mark of royalty and extreme wealth and a prestigious symbol of those:

“born to the purple.”

Known as royal purple or Tyrian purple after the main distribution point of Tyre, it was worn only by kings and high priests.

Thus, this expensive and profitable trade item gave the Hyksos merchants their special entry into the palaces and homes of the leaders of society wherever they traveled.

The language of these Hyksos merchant moneylenders was Canaanite, the same language as the shepherd Hyksos with outlying tribes speaking the related dialects of Hebrew and Aramaic.

These were the languages that they spoke when they first invaded Egypt and which they still spoke as they made their escape out of Egypt.

In terms of:

- archaeology

- language

- religion

there is little to set those Hyksos apart as markedly different from the other tribes of Canaan.

They were Canaanites.

In the Amarna tablets, they called themselves Kenaani (Canaanites).

But we know them today as Phoenicians because of their monopoly of the purple dye.

Their first and most important customers were the Greeks.

The Greeks called the purple dye, “phoenix” meaning “purple-red”, hence the Greek name phoinikèia or “Phoenicia”.

Miles Williams Mathis: Phoenicians – Where did they ALL Go? – Library of Rickandria

But whatever name they were called, whether Phoenicians, Tyrians from Tyre, Sidonians from Sidon, etc., they were the same Semitic gangs of thieves and moneylenders who had originally joined together with their Babylonia leaders to loot Egypt.

And now that they had escaped, they were looking for new opportunities for profits doing what they did best, buying and selling and profiting from the Sumerian Swindle.

Herodotus (~460 BC) tells us that the Phoenicians:

“came originally from the coasts of the Indian Ocean; and as soon as they had penetrated into the Mediterranean and settled in that part of the country where they are today, they took to making long trading voyages.

Loaded with Egyptian and Assyrian goods, they called at various places along the coast, including Argos, in those days the most important of the countries now called by the general name of Hellas.

“Here in Argos, they displayed their wares, and five or six days later when they were nearly sold out, it so happened that a number of women came down to the beach to see the fair.

Among these was the king’s daughter, whom the Greek and Persian writers agree in calling Io, daughter of Inachus.

These women were standing about near the vessel’s stern, buying what they fancied, when suddenly the Phoenician sailors passed the word along and made a rush at them.

The greater number got away; but Io and some others were caught and bundled aboard the ship, which cleared at once and made off for Egypt” [309]

Even though the event described took place before 539 BC, nearly a thousand years later than the present time that we are studying, it does give an account of the methods and morals of the Phoenician merchants and shows that they were still thieving Hyksos bandits and slavers even as late as Herodotus’ time.

Although Herodotus’ information was partially correct in that the Phoenicians came from the direction of the Indian Ocean, he didn’t understand that they were the Sea Captains for the Babylonian merchant-moneylender guilds.

The Phoenician leaders and captains came from the Persian Gulf, from the direction of India, but they did not come from India.

Their original home ports were the cities of Babylonia.

But now that they had moved into the Mediterranean Sea, their main, fortified harbor and shipyard was at Tyre.

And with their Babylonian and Assyrian guild partners, they soon had plenty of:

- Egyptian

- Assyrian

- Babylonian

goods with which to trade.

These trade goods included the debt-slaves who were becoming so numerous in Babylonia as well as the war-slaves captured by Assyria.

And of course, the prettiest women fetched them the most profits.

The Phoenician alphabet was developed from the Proto-Canaanite alphabet during the 15th century BC which they learned from Egyptian hieratic script.

Before then, the Phoenicians wrote in cuneiform script on clay because they were the sailors and sea captains of the Babylonian tamkarum [merchant-moneylender] Persian Gulf trading fleets.

They switched to an alphabet because it is a simpler and more efficient way of communication than was the complicated Mesopotamian cunieform.

As they expanded their Mediterranean trading fleets, they introduced the alphabet writing system to other peoples.

EDUCATION: Is the English Language Really Reversed Hebrew? – Library of Rickandria

The Canaanite alphabet evolved into Proto-Hebrew/Early Aramaic and finally into Hebrew.

And the idea was taken up and improved upon by the Greeks.

As Hyksos merchants, the Phoenicians began a seafaring enterprise of trade and moneylending that brought them great wealth.

Where else could these tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders] and pirates go but out to sea?

The Mediterranean Sea was new territory for them.

To the south and southwest, Egypt had just chased them out and was more interested in killing them than doing business.

To the north, an emerging Indo-European power known to us as the Hittites was beginning to expand.

To the east, the empires of Babylonia and Assyria would allow no trade competition in their territory.

So, these Amorite tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders] and fugitive Hyksos used the profits that they had made in the looting of Egypt to build ships and warehouses.

From Tyre, they sailed off to the unfettered expanse of the Mediterranean Sea to build the Phoenician trading and money-lending empire.

There was no difference between the Apiru goat rustlers who had wandered about in the deserts of Sinai and the Apiru who had been trapped and enslaved in Egypt.

There was no difference between the Apiru thieves who slinked about the hills of Canaan and those Apiru in the coastal cities who had become known as Phoenicians.

There was no difference between any of these Hyksos either culturally or linguistically.

But because of their geographical locations and their methods of livelihood, all of these Semites had a very different history from one another from 1550 BC onward.

The slaves, the goat-rustlers of Sinai and the bandits of Palestine all separated and then later merged together as you shall see.

But the Apiru known as Phoenicians set sail on an entirely different and an entirely independent tact through history.

Building on the profits that they had made in looting Egypt, speaking a dialect of Hebrew, praying to the Canaanite gods, dealing in slaves, precious metals and moneylending, sailing their ships to wherever a profit could be made, these Phoenician [merchant moneylenders] had no intention of returning to Babylonia when so much silver could be made from the countries of the Mediterranean Sea and beyond.

They had ready sources for manufactured trade goods from Assyrian and Babylonia and eventually from Egypt but their customers for these goods were in the Mediterranean.

In addition to their skills as traders and merchants, they carried with them wherever they went, the Sumerian Swindle with which to enslave and defraud the peoples of:

- Greece

- Europe

- North Africa

The Phoenicians were not just traders, they were also loan sharks.

It was not just with their monopoly of purple dye that they profited.

It was not just with their Sumerian Swindle with which to enslave the peoples of the Mediterranean.

The simple fact that they were the middlemen in the transportation of goods, gave them an additional advantage over the other peoples of the Mediterranean – an advantage that they lost no time in exploiting.

These Phoenician traders profited from Secret Fraud #18 of the Sumerian Swindle:

“When the source of goods is distant from the customers, profits are increased both by import and export.”

With their fleets of ships, the Phoenicians could transport and trade the products of the:

- Near East

- Europe

- North Africa

and the Black Sea.

By keeping the source of goods, a secret and the market for the goods saturated with their peddlers and agents, the profits were enormously increased simply because of the resulting monopoly.

Their home ports were the coastal cities of Canaan which was the cross-roads of all trade routes from the distant sources of:

- Assyria

- Babylonia

- Persia

- India

- Arabia

and even China.

As middlemen, they could transport the goods of the entire known world on their fleets of ships.

The ships of the ancient peoples sailed and rowed, hugging the coasts during the mild seasons.

The smaller ships were designed to be easily beached and refloated upon sandy inlets or else find a protected cove and ride at anchor for the night.

The Phoenicians were the first ancient people to sail at night using the stars and also to sail in the winter.

Phoenician culture was organized into city-states like those of Mesopotamia.

Each city-state was an independent unit politically, although they could come into conflict with one another, be dominated by another city-state, or collaborate in guild alliances, much in the same manner as the roving Amorite tribes.

Each city was organized around its own merchant-moneylender guild.

These cities were led not by kings but by priests whose chief god was the Canaanite deity, Ba’al.

This storm god was equally important both to the shepherds of the wilderness and the sailors upon the sea.

But as useful as this system was to those cities, the Phoenicians had a major weakness.

Being among the elite of the Hyksos who had escaped from Egypt, they were predominantly populated by leaders rather than followers.

Normally, the city-states that had arisen throughout the ancient Near East during the previous 2000 years had had a natural balance of a few leaders, many merchants, a larger number of military, all supported by a much larger number of farmers and laborers.

But the Hyksos who had settled in the Canaanite cities were not supported by either farmers or military since these had been among the Hyksos:

- foot soldiers

- shepherds

- thieves

who had run off into the wilderness of Canaan and Sinai or who had been enslaved in Egypt.

The Phoenicians were mainly merchants and gang leaders with a few high ranking soldiers among them.

They were “Haves” who did not have enough “Have-Nots” to support and protect them.

They were short of:

- laborers

- farmers

- soldiers

The Phoenicians made up for this deficiency because they had the wealth with which to hire whatever help they needed.

The Canaanite cities that they had inhabited had sufficient:

- farmers

- fishermen

- workers

to serve their needs of food and labor.

Whenever they needed bodyguards or soldiers, they would hire mercenaries.

So, the initial labor shortage was at first not a problem.

Their cartels of independent seaports, with others on the islands and along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, were ideally suited for trade throughout the entire region.

But the Phoenician home ports in Canaan were surrounded by militant neighbors.

A decade or so before they were kicked out of Egypt, a volcano in the Aegean Sea exploded.

The explosion of Thera sent 100-foot-high tsunamis crashing against the island of Crete.

These monstrous waves wiped out the seaside cities and ships of the Minoans.

The Minoans had had a virtual monopoly on sea trade for hundreds of years before this volcanic explosion.

They had had temples and warehouses in the Hyksos city of Avarice where they had traded with the Hyksos for Egyptian loot.

The Hyksos and the Minoans had been trade partners whose highest ideal was making a profit in trade.

But the Minoans had had the shipping monopoly in the Mediterranean.

Across the Aegean Sea, the rowdy Mycenaean Greeks were less interested in trade than they were in war.

The main interest of these warrior Greeks was heroic adventures through warfare and the ideals of a noble death in battle.

Although they were not shy about making money through the booty of war, mere business and trade was never their top priority.

Their heroes have come down to us in such stories as Homer’s Odysseus and the siege of Troy.

With fierce and idealistic warriors such as these, the materialistic Phoenicians had little in common and in battle no chance of success.

But once the Minoans had been erased from the scene with tsunamis and layers of volcanic pumice, the ever war-like Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland were quick to raid the devastated islands of Crete to salvage what treasures that they could and to establish themselves as the inheritors of the Minoan trade.

Even though the Thera explosion had removed the Minoans and their large fleet of ships from direct competition with the Phoenicians, this did not freely open up trade in the Aegean Sea for the Phoenicians.

The Mycenaeans of Greece with their many and mighty ships were able to replace the Minoans in sea trade in the Aegean Sea and on both Cyprus and Crete.

They prevented the Phoenicians from monopolizing trade in the north simply through superior military strength.

The Mycenaean Greeks were not as successful at trade as the Phoenicians were because:

- ethics

- fair play

- honor

and honesty was a part of their national character.

But at warfare, they were supreme and skillful experts.

So, the Phoenicians dared not oppose them openly.

However, their tamkarum [merchant moneylender] methods of trading both with the Greeks as well as with all of the enemies of the Greeks, began to reap its rewards.

And their use of the Sumerian Swindle gave the Phoenicians a money-making engine that funneled silver into their coffers beyond anything that trade alone could bring in.

Loan sharks in every port, lending-at-interest, soon created a network of money-siphons sucking the silver and gold out of every country where Phoenician ships made land fall.

This combination of import monopolies and moneylending gave the Phoenicians the wealth to finance a successful trade empire.

Their craftiness at trade was apparent to all; but the Secret Frauds of the Sumerian Swindle, as the engine behind their growing trade empire, was hidden from all.

They were both tradesmen and parasites because that is:

“how they had always been.”

The Phoenicians profitably enlarged their trading contacts along the North African coast and circled around Iberia to the Atlantic.

They traded with the Greeks because they had what the Greeks wanted, the purple dye, colorful garments and quantities of:

- exotic perfumes

- gemstones

- incenses

And the Greeks had:

- gold

- silver

- beautiful female slaves

who brought high prices in Egypt and North Africa.

Their trade with the Greeks allowed them access to the Black Sea where lived the peoples who were traditionally the favorite customers of the merchant-moneylenders – that is, people who were illiterate, gullible and easily deceived.

While the Phoenicians expanded trade with the Libyans along the North African coast, which was freely open to the first ones who could make the voyage, they continued their trade with the Greeks.

But close to their home ports in Canaan, the ancient city of Ugarit was becoming a major competitor.

Not content to control the major trade routes from Mesopotamia and the grain and metals trade with the Hittites, and seeing the profits being made by the Phoenicians, the tamkarum [merchant-moneylender] guilds of Ugarit also began to build ships for the Mediterranean markets.

This was a direct competition with the Phoenicians.

What was just as bad, Ugarit was better situated to control the trade routes from Mesopotamia than were the Phoenician cites on the Canaanite coast.

Those routes had to pass through Ugarit before they reached Phoenicia.

So, the Phoenicians were being blocked by the Greeks to the north and taxed on their trade goods by Ugarit to the north and east.

To add to their insecurity, the Hittites, an Indo-European people, were increasing their territorial expansion across lands in Anatolia to the north of the Phoenician cities.

Though a Hittite attack on the Phoenician cities was always a threat, it was the combination of both the Hittites and the city of Ugarit that was the most dangerous.

Ugarit supplied grain to the Hittites and the Hittites traded:

- silver

- iron weapons

- horses

to Ugarit.

The fortunes of one were tied to the fortunes of the other.

In addition, the trade guilds of Mesopotamia (and therefore the related trade guilds of the Phoenicians) had only a minor presence among the Hittites.

The Hittites preferred to keep a wary eye on the greedy merchants from Assyria and Babylonia and to restrict their market access by dealing with Ugarit as the middleman.

In addition, Egypt was crowding the Phoenicians out from the south.

Twenty years after the Hyksos had been expelled from Egypt, Pharaoh had sent his armies up the Canaanite coast and demanded to be recognized as overlord of the region.

For the Egyptians, this was mainly a defensive method for creating a buffer zone around Egypt.

After 1500 BC, although the Phoenicians retained a great deal of independence under this arrangement, they were subjected to heavy demands for tribute which was theoretically buying Egyptian protection.

But as the Amarna letters show, Egypt was not interested in protecting, nor was she able to protect, anyone in Canaan even against the petty gangs of Hebrew goat rustlers and bandits.

So, Phoenicia was paying tribute and receiving no protection in return.

This strained political climate lasted for about 150 years as Phoenicia expanded its maritime trade across North Africa.

During this time the Hittites continued to press southward.

They engulfed Ugarit and came to the borders of Phoenicia.