The Sumerian Swindle: How the Jews Betrayed Mankind – (5000 BC to 1500 BC) – Chapter 5: Daily Life in Sumeria

The quality of life in any country can be best understood by whether or not the People have for themselves the Eight Essentials of Life.

This is an ancient knowledge but one that you can use to question the quality of your own life and the success of your own race and your own country.

These Eight Essentials of Life may seem like a simplistic way of looking at civilization and at happiness, but why make things complicated when happiness is so easy to understand?

The Eight Essentials of Life are:

- Air

- Water

- Food

- Clothing

- Shelter

- Spouse

- Children

and God.

When people have all of these, then life is good, and the people are happy.

You can measure the quality of your own life by considering these Eight Essentials and whether or not you have them, yourself.

But for now, let’s just see how these affected the people of Sumeria and the other peoples of the Ancient Near East.

There was not much problem with the Sumerians having enough good air to breathe.

Not having air pollution to contend with as we do in modern times, they had plenty of fresh air everyday unless of course a dust storm blew in from the desert.

So, both the “Haves” and the “Have-Nots” were equal in this regard.

Although not everyone knew the priestly and religious secrets of meditational breathing, everyone at least had fresh and unpolluted air to breath.

Also, water was not much of a problem.

Although they lived in the semi-arid and desert conditions of the Fertile Crescent, the water of the Euphrates and Tigress rivers and their tributaries provided plenty of water.

And the water table was high enough for wells to be dug.

However, not knowing of water-borne diseases or of bacteria, all levels of society suffered from such things as dysentery and a variety of infections and lung ailments.

After all, these were farming communities always in close contact with dirty animals and the bacteria and toxic mold spores from dung piles.

And their houses were made of mudbricks, so filthy conditions where a small scratch could lead to severe infections were a constant part of life.

The average life span was just forty years.

Food is the third Essential of Life.

However, this is where the awilum [Haves] and the muskenum [Have Nots] began to experience different qualities of life.

As most people will agree, food is not just a necessity, but it is also one of the pleasures of life since the delicious flavors that can be derived from good cooking are so nice.

Much can be deduced about any people by studying the food that they ate.

In Mesopotamia, with its hot sun and fertile soil, two crops per year of a large variety of foods were grown.

Compare what you find at your local supermarket with the foods enjoyed by these ancient people, and you will see that they had just as great a variety.

The basic food of all Sumerians was, of course, grain.

Barley was the chief grain of Sumeria primarily because it could grow in a more alkaline soil than could wheat.

Wheat was grown in the higher elevations, but for the irrigated lands of Mesopotamia where the evaporating and percolating irrigation water raised the salt content of the soil, barley was the staple crop.

Other cereals eaten, besides barley and wheat, were millet and rye.

These were eaten either as unleavened breads that were either baked or roasted as thin disks upon a hot griddle (as is still done in the Middle East today) or cooked into thick porridges.

Rice was not cultivated until the first millennium BC.

- Onions

- leeks

- shallots

and garlic were basic to the ancient diet.

Their savory flavors and healthful qualities were as much appreciated then as they are today.

Onions were described in the cuneiform texts as being sharp, sweet, or those:

“which have a strong odor.”

In their extensive gardens, the farmers also grew:

- lettuce and endive

- melons and gourds

- lentils

- beets

- carrot-like plants

and fennel bulbs.

- Lentils

- beans

- chickpeas

were plentiful and when eaten with the various grains, provided a balanced and wholesome diet.

Other vegetables included a:

- variety of lettuces

- cabbage

- summer and winter cucumbers (described as either sweet or bitter)

- radishes

- beets

and a kind of turnip.

Fresh vegetables were eaten raw or boiled in water.

Many herbs and spices were available, such as:

- salt

- coriander

- black and white cumin

- mustard

- fennel

- marjoram

- thyme

- basil

- mint

- rosemary

- fenugreek

- watercress

- saffron

and rue (an acrid, green leafy plant).

Dates were an important part of the common diet, while the palm also provided date sugar and date wine, as well as a celery-like delicacy cut from the growing heart of the male palm.

They made sweet date syrup from the dates.

And of course, because they were easily dried and preserved, dates were a valuable trade commodity with foreign lands.

The Sumerians did not use sugar; instead, they substituted fruit juices, particularly grape and date juice.

And so, their teeth were not rotten like the teeth of modern people who suffer from the Jewish Medical Swindles as described in Volume III, The Bloodsuckers of Judah.

Only the very rich could afford honey, which may have been imported.

“Mountain honey” as well as “dark,” “red,” and “white” honey were mentioned in cuneiform texts.

Other fruits commonly grown were:

- apples

- pears

- grapes

- figs

- quince

- plums

- apricots

- cherries

- mulberries

- melons

- medlar

- peach

- pomegranates

as well as pistachios.

Meat was also a part of the ancient Mesopotamian diet.

Massive reed barns housed numerous flocks and herds, which were then redistributed for sustenance and cultic needs.

The animals were delivered alive and then slaughtered by a butcher.

But some animals were dead on arrival.

Both types of meat were considered f it for human consumption.

The meat from already dead animals was fed to:

- soldiers

- messengers

- cult personnel

Dead asses were used only as dog meat.

- Poultry

- geese

- ducks

were raised for meat and eggs; the hen was introduced from India in the first millennium BC along with rice culture.

Mutton, and less commonly beef, were eaten at festivals, and in the earliest times offerings of goats were a regular feature of peasant worship and presumably an equally regular part of peasant diet.

But as the moneylenders increased their wealth, there was a corresponding reduction in the wealth of the people, so the ordinary peasant could less afford goat meat in his diet because his pay for his labor was reduced so much.

Pig meat was regularly eaten since wild pigs were found in the southern marshes and domestic pigs were raised in large herds.

As scavengers, they could eat anything, and barley was provided to them as a supplement.

Since fat is usually in short supply in primitive diets, fat pork was considered a delicacy.

A Sumerian proverb makes the point that it was too good for slave girls, who had to make do with the lean ham.

Because of the shortage of suitable pastureland, cattle were relatively few in number.

Horseflesh was eaten by humans without involving any religious taboo, at least in the Nuzi area east of Assyria in the fourteenth century BC, and a lawsuit is recorded in which the defendants had stolen and eaten a horse.

The Sumerians also drank milk:

- cow’s milk

- goat’s milk

- ewe’s milk

Milk soured quickly in the hot climate of southern Iraq.

NEW WORLD ORDER: IRAQ: Destroying Our Past – Library of Rickandria

Ghee (clarified butter) was less perishable than milk, as was the round, chalky cheese, which could be transformed back to sour milk by grating it and adding water.

The texts do not mention the processing of sheep’s milk before the Persian period, at which time it was made into a kind of cottage cheese.

Other dairy products included yogurt and butter.

Many kinds of cheeses were produced:

a white cheese (for the king’s table)

“fresh” cheese

and:

- flavored

- sweetened

- sharp

cheeses.

The rivers were filled with:

- fish

- turtles

- eggs

A Sumerian text (~ 2000 BC) described the habits and appearance of eighteen species of fish including:

- carp

- sturgeon

- catfish

and eels.

Fish was an important source of protein in the diet.

In addition to beer and date wine, wine from the grape was known as early as the Proto-literate period (3200-2900 BC), probably as an import from the highlands; it was not in that early period a drink in everyday use.

Such fermented beverages, which probably contained a good deal of lees, were in the Sumerian period imbibed from a common vat through hollow reeds, of which the end was perforated with small holes to form a kind of filter.

Beer was an important part of the Sumerian diet and there were many varieties.

The literal translation was “barley beer.”

The Sumerians at Ur enjoyed:

- dark beer

- clear beer

- freshly brewed beer

and well-aged beer as well as sweet and bitter beers.

They did not use hops for flavoring.

Ration lists for palace employees recorded the distribution of one quart to one gallon of beer a day, depending on the rank of the recipient.

Throughout Mesopotamian history, brewing was in the hands of women, for this craft is the only one which was under the protection of female divinities, while the alewife is specifically mentioned in the laws of Hammurabi.

Unlike beer, wine could be made only once a year, when the grapes ripened, but wine had a longer shelf life when stored in a sealed jar.

It was referred to as a very expensive and rare commodity, found in areas of natural rainfall in the highlands.

Many wines were named after their places of origin.

Though wine consumption increased over time, it was still a luxury item, served only to the gods and to the wealthy.

Only women ran the wine shops where certain priestesses were prohibited from entering upon penalty of death.

Other products of the vine included:

- grape juice

- wine vinegar

- raisins

As you can see, with all of this great variety of foods, the Mesopotamian peoples had everything that they needed to cook some delicious and healthful foods.

Cereals were made into pastry, cakes or biscuits by cooking the flour mixed with:

- honey

- ghee

- sesame oil

- milk

or various fruits.

Soups were prepared with a starch or flour base of:

- chickpeas

- lentils

- barley flour

- emmer flour

- onions

- lentils

- beans

- mutton fat or oil

- honey

or meat juice.

The soups were thick and nourishing – a meal in a bowl.

Many foods were preserved for times of need.

Grains were easy to keep and when properly stored could last for decades.

Legumes could be dried in the sun.

A variety of fruits were pressed into cakes.

Fish and meat were preserved by:

- salting

- drying

- smoking

During the winter, ice was brought from the highlands, covered with straw and stored in icehouses for cooling beverages even during the hottest summers.

Thus, it can be seen that the Sumerians and the people of Mesopotamia were well stocked with food.

Indeed, the bountiful harvests of the Fertile Crescent region are what supported these people in attaining the higher levels of civilization.

With abundant food from an agricultural base, they were not restricted in their cultural advancement like their nomadic neighbors who relied upon the unreliable hunting and gathering and the nomadic shepherding of goats.

The Sumerians ate two meals a day.

They bragged about their highly developed cuisine and compared it to that of the desert nomads, whom they believed had no idea of the ways of civilized life.

They described the nomads as eating raw food and not even knowing how to make a cake with:

- flour

- eggs

- honey

[32] [33]

Such an abundance and variety of food caused the hungry goat-herders of the surrounding countries to covet those fruitful lands of Mesopotamia.

With food, the Third Essential of Life, well supplied, what did the Sumerians do for clothing?

Spinning and weaving was an art known since Paleolithic times.

Because the Sumerians kept sheep and goats, the wool clothing that they made kept them warm in the winter.

And they grew flax that produced a light cloth for summer months.

But since the generally hot weather required few clothes at all, Clothing, the Fourth Essential of Life, was also well supplied to these people.

The Fifth Essential of Life is shelter.

Again, this was easily supplied by the natural surroundings.

The people who lived in the marshes of Sumer, had learned how to build rather large and beautiful houses out of the giant reeds that grew there in abundance.

These were used both for housing and for barns for their small cattle and as pens for ducks and geese.

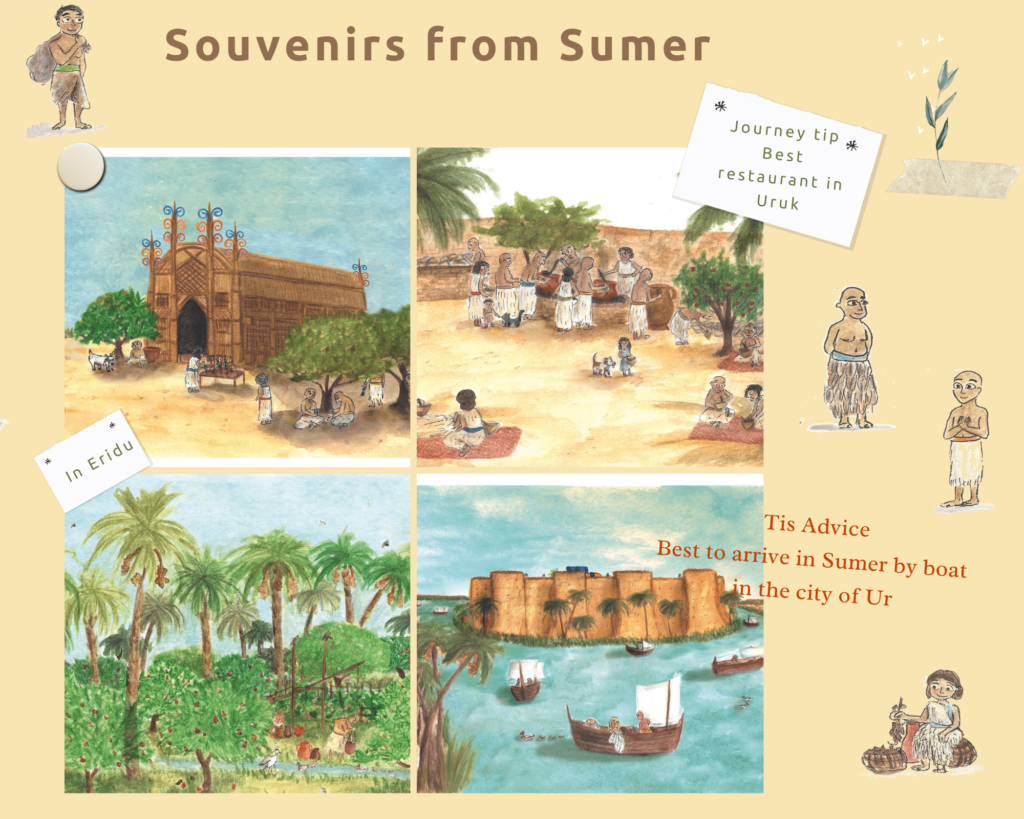

Such reed houses are still used today in southern Iraq by the so called “marsh Arabs”. [Figure 5]

And of course, Mesopotamia is famous for its large cities made entirely of mud bricks.

As any child knows, mud can be made into many things besides mud pies.

And when it dries, it is almost:

“as hard as a rock”.

From mud bricks, huge temples were built reaching eighty feet above the plains.

Entire cities with double-storied houses, domed roofs and arches, sewer drainage systems and town walls were made entirely from mud bricks, both sun-dried for common work and baked bricks for fortifications, drainpipes and palace facades.

With food and shelter well-supplied, the Sumerians found that the Sixth Essential of Life, a spouse, was not difficult to find or to care for.

Marriage (throughout the whole of Sumerian and Babylonian society) was monogamous in the sense that a man might have only one woman who ranked as a wife and who enjoyed a social status corresponding to his.

But for a man to also go the Temple to enjoy “praying” with the temple prostitutes, was not something for an obedient wife to complain about.

And once the moneylenders had perverted society enough by turning the wives and children of their “clients” into whores and slaves, it became a normal part of Mesopotamian society to make use of the female slaves as sex slaves.

The offspring of such unions were carefully legislated in the surviving law codes.

There were few, if any, bachelors in Mesopotamia. [34]

As you shall see, slavery grew because of the growing national and private debts of the people to the moneylenders.

As slavery increased, sexual exploitation became an ever-increasing pleasure of the moneylenders and merchants who owned them.

The Seventh Essential of Life are children.

Most civilizations know children provide help for the parents in old age and are thus a savings account toward the later years.

With children, society is assured a strong and bright future.

And with children, parents can experience the fulfillment and the immortal nature of their lives, and they can assure themselves of comfort in their old age.

Although most people in those days did not live into old age, at least with children, they could more easily make a living because children became workers in the fields and shops very early.

The moneylenders made good use of children because they could hire a man and his boys to work the fields and pay only for the man.

However, even though civilization was successful in Mesopotamia, and even though the country had attained a population of one million by the third millennium BC, life expectancy was still rather short.

The average life expectancy was about 40 years although many lived to be older.

Fifty, sixty or ninety years were not unknown.

In a wisdom text from the Syrian city of Emar, the gods allotted Man a maximum lifetime of 120 years.

To see one’s family in the fourth generation was considered the ultimate blessing of extreme old age.

We know that the mother of King Nabonidus lived for 104 years – she told us so in her autobiography.

Archives have shown that some individuals lived at least seventy years.

But as the moneylenders manipulated the kings and their countries into wars, not old age but battle casualties became the major cause of death among adult males. [35]

Finally, with the Eighth Essential of Life, their God to protect and nurture them, the Sumerians had everything that life could offer.

The fertile land produced abundant crops and there was enough food for everybody as well as a huge excess for trade.

With their flocks of sheep and goats and fields of flax, there was enough wool and linen clothes to protect them from both heat and cold.

The mud and the reeds gave them shelter.

The work in the fields gave them food.

Yes, there was enough for everybody.

That is, there was enough for everybody except for the moneylenders of the Treasonous Class who already had more than they could ever use.

For those greedy and voracious parasites, nothing could satisfy them because there was an entire world that they did not own — yet.

And so, even though there was enough of everything for everybody, the food and the goods were not everywhere equally abundant because there were only two social classes that had evolved in this Cradle of Civilization, this Fertile Crescent, this land of Sumeria and Babylonia and Assyria, this land of Mesopotamia.

There was enough for everybody but not everybody had enough.

This was because the two classes of the awilum [the Haves] and the muskenum [the Have-Nots] were all that were allowed to exist since the “Haves” got what they had by taking it either by force or by fraud from the “Have-Nots.”

Under a system where the Sumerian Swindle was allowed to exist, there could only be Haves and Have-Nots and Slaves because the fraudulent nature of lending-at interest mathematically and automatically swindled all wealth into the hands of the awilum [the Haves].

Under the relentless arithmetic of the Sumerian Swindle, the Treasonous Class was determined that for them to continue to be the “Haves” then that meant that everyone else would have to continue to be the “Have-Nots”.

The awilum [Haves] got everything that they had from the muskenum [Have-Nots].

And to keep what they got meant that they could not give any of it back.

The muskenum [Have-Nots] accepted this state of affairs because they did not understand the Sumerian Swindle for what it was.

They believed that owing more than you borrow was:

“a normal part of life”

simply because the Sumerian Swindle:

“had always been here.”

Defrauding the Peasants As population and land use increased, it was necessary for the various farms and gardens on arable land to be carefully plotted, measured and the boundaries marked.

Of course, the scribes were the only ones who knew how to calculate land sizes and to make measurements.

They could also read and write the:

- sales contracts

- mortgages

- rentals

- leases

and work agreements on the clay tablets for all to see.

A good memory was not enough once writing became the basis of contracts and agreements.

If a peasant could not read, then he was dependant upon the scribes.

However, trickery and deceit were a valued talent in Mesopotamia.

Those with the money, education and avarice tended to oppress and dispossess those without these attributes.

No matter how blatant the fraud, the poor had little defense from the ravages of the rich, just as in modern times.

Their only protectors were the priests who preached mercy for the muskenum [Have Nots] and who disapproved of the evils practiced by the awilum [Haves].

Even though there was plenty of land available for crops, this land could not produce a harvest without huge expenditures of labor.

Canals and irrigation ditches needed to be dug, the soil needed to be:

- plowed

- furrowed

- harrowed

- raked

- watered

- weeded

and tended, all meticulously with hand tools and an ox-drawn plow.

Birds needed to be frightened away.

The investment in labor by the farmers was immense.

The house that they built out of mud bricks, was both back breaking labor and a labor of love by men who enjoy working on their own land with their own hands.

Hard work did not mean that the work was without joy.

Being close to Nature and close to God were some of the joys of farming just as they are today, although the work in those days was more strenuous since it was all done with hand tools and with oxen or the wife and kids pulling a single-bladed plow.

This huge amount of labor with hand tools and ox-drawn plows was necessary to turn raw desert into a bountiful farm.

It was labor paid for by the sweat of the entire farming family.

- Parents

- children

- grandparents,

all did the work.

Since the life expectancy was only about forty years, the grandparents were still young enough to work until their dying day.

It was this huge amount of labor, the countless hours between sunup and sundown, the months and years laboring under the hot sun without pay but with the hope of a good harvest; it was this as well as the land itself that the moneylenders stole when they foreclosed a family farm.

They did not foreclose on empty, undeveloped land.

Just as the bankers do today, they waited until all of the work had been done and the crop ready to harvest before swindling the peasants out of their labor, their produce, and their property.

The man-years of labor plus the price of the land plus the cost of whatever mud-brick buildings that were part of the farm, would make it too expensive for the moneylenders to buy and then resell for a profit.

The farms were too expensive to buy but not too expensive to steal.

Secret Fraud #2 of the Sumerian Swindle brought the moneylenders huge profits:

The farmer and the merchant have both borrowed one shekel of silver and they must each repay a shekel and a half to the moneylender.

If both the farmer and the merchant have a bad year and cannot repay even the shekel that they borrowed, the moneylender takes the farmer’s farm and takes the merchant’s shop and house as recompense.

And so, the moneylender gets an entire farm, a shop and a house for only two shekels.

These, he can sell for many shekels worth of grain and other goods.

So, his profits are enormous.

“Collateral that is worth more than the loan, is the banker’s greatest asset”

was a great swindle.

It is the pawn-broker’s method that is still used today.

This technique was used by the moneylenders of 4000 BC – even if they lost their principle, they gained even more by confiscating the collateral.

Even if the principle was repaid, if the interest was not repaid, then they would not only get their principle back, but they could additionally confiscate the property of the debtor as well!

This was a powerful discovery!

They could make money-on-a-loan and also make money even when the loan went bad.

Indeed, because of the intrinsic fraud of the Sumerian Swindle, some loans would always go bad.

Under the relentless arithmetic of the Sumerian Swindle, it was difficult to lose when lending either grain or silver.

The arithmetical numbers are eternally unwavering, and the fate of mortal man is eternally at the mercy of both gods and moneylenders.

When the principle and interest are repaid, there is a profit.

And when the loan is not repaid, there is still a profit.

But this was just the very simple beginnings of the business science of legalized crime that has been passed down to modern man in the form of:

- banking

- mortgages

- credit card debt

This list does not make much sense now, but each point is explained in the following chapters.

The Sumerian Swindle has twenty-one secret frauds.

The Twenty-One Secret Frauds of the Sumerian Swindle are:

#1 All interest on the loan of money is a swindle.

#2 Collateral that is worth more than the loan, is the banker’s greatest asset.

#3 Loans rely on the honesty of the borrower but not the honesty of the lender.

#4 Loans of silver repaid with goods and not with silver, forfeit the collateral.

#5 The debtor is the slave of the lender.

#6 High morals impede profits, so debauching the Virtuous pulls them below the depravity of the moneylender who there-by masters them and bends them to his will.

#7 Monopoly gives wealth and power, but monopoly of money gives the greatest wealth and power.

#8 Large crime families are more successful than lone criminals or gangs; international crime families are the most successful of all.

#9 Only the most ruthless and greedy moneylenders survive, only the most corrupt bankers triumph.

#10 Time benefits the banker and betrays the borrower

#11 Dispossessing the People brings wealth to the dispossessor, yielding the greatest profit for the bankers when the people are impoverished.

#12 All private individuals who control the public’s money supply are swindling traitors to both people and country.

#13 All banking is a criminal enterprise; all bankers are international criminals, so secrecy is essential.

#14 Anyone who is allowed to lend-at-interest eventually owns the entire world.

#15 Loans to friends are power; loans to enemies are weapons.

#16 Labor is the source of wealth; control the source and you control the wealth, raise up labor and you can pull down kings.

#17 Kings are required to legitimatize a swindle but once the fraud is legalized, those very kings must be sacrificed.

#18 When the source of goods is distant from the customers, profits are increased both by import and export.

#19 Prestige is a glittering robe for ennobling treason and blinding fools; the more it is used, the more it profits he who dresses in it.

#20 Champion the Minority in order to dispossess the Majority of their wealth and power, then swindle the Minority out of that wealth and power.

#21 Control the choke points and master the body; strangle the choke points and kill the body.

During the period of high Ubaidian Culture between 5000-4000 BC, while the Ubaidian people were founding the ancient cities of:

- Adab

- Eridu

- Kish

- Kullab

- Lagash

- Larsa

- Nippur

and Ur, the Ubaidian moneylenders were busy defrauding and swindling their own people out of their lands and property by using only simple interest.

But the secret did not really become a major power in the world until after the arrival of the Sumerians and the invention of writing and numbers.

What had been a swindle at a local level using counting beads and clay markers became an incredibly profitable scam supported by the invention of numbers and writing.

With writing and arithmetic, compound interest became the main engine of the Sumerian Swindle.

But before delving into this history, let’s look at this metallic part of the Swindle a bit more carefully.

In the ancient societies where silver was used as a form of money, manipulation of the availability of this commodity metal produced even greater profits.

What happens when the farmer actually has a good year?

He has borrowed one shekel of silver and must repay a total of one and a half shekels of silver.

But there are only two shekels in the entire world and the banker has kept the second shekel hidden in his strong box and out of circulation.

The farmer sells his goods in the market and returns to the moneylender saying,

“Here is your one shekel back but I cannot find another half shekel of silver to pay you for interest on the loan.

And so, I will pay the interest with produce from the farm.”

Thereby, the farmer wants to pay the banker with one shekel of silver and a half shekel’s worth of barley.

That seems fair, doesn’t it?

But the moneylender, knowing that there are only two shekels and that he is hiding one of them, says,

“Our agreement was to repay the loan of one shekel of silver with a shekel and a half of silver.

The loan was for silver and the repayment must also be in silver.

Since you have paid back the one shekel principle in silver but not the half shekel of interest in silver, you forfeit your collateral.

I will not accept repayment of the interest in trade goods of equal value because the agreement was to be repaid in silver.”

Because the banker had created a shortage of a commodity metal like silver, he was again asking the impossible.

And when the impossible could not be met, the banker seized the real property of the debtors and got it for free even though the debt could easily have been repaid with trade goods of equal value.

And so, Secret Fraud #4 of the Sumerian Swindle is:

“Loans of silver repaid with goods and not with silver, forfeit the collateral.”

The banker again is able to seize the farmer’s farm even when the principle is repaid because the interest was not repaid in silver.

The banker demands to be repaid one-half shekel that, in fact, did not exist in circulation because it was hidden in his vault.

The two debtors believed that the shekel existed but which he has been unable to earn through his labor because the world is so big that he cannot imagine that its supply of silver is so small that it can be hoarded by just a few men.

And so, the People believe that what the banker demanded could not be met and so they believe that they still owe the banker this impossible sum.

And since they believe that they owe the money, then they accept the swindle as being an honest business error on their part.

They blame themselves for being unable to earn the silver when the banker knows full well that it is impossible to earn since it either doesn’t exist or he is keeping it hidden away in his strong room.

So, the farmer and the merchant hand over their property to the banker.

And the thieving banker is not in a hurry to explain their error in judgment because a sucker in born every minute.

In reality, there are many more pieces of silver in the world than just two.

So, in real life, not all of the people are defrauded equally.

But the technique is the same.

Even with many millions of pieces of silver, there are always fewer in circulation than what the account books claim are due.

Even though everybody in society is being swindled by the bankers and moneylenders, those who are able to earn enough to pay their debts, feel safe and superior to those who become impoverished.

So, the Sumerian Swindle is perpetuated because the winners feel superior to the losers; or if not superior, then at least glad and thankful that they are “winners” and not “losers”.

When moneylenders are allowed to lend at interest, everyone in society is a loser except the moneylenders, as you shall see.

But to continue with this example, let’s say that the merchant has a good year and makes a shekel and a half of the two shekels in circulation, and the farmer has a bad year and only gains a half shekel.

The merchant feels confident and successful in having repaid the loan, more so because he sees the farmer’s land confiscated and the farmer’s wife and children dragged off in slave’s collars.

With his profits, the merchant may even buy up the confiscated land from the moneylender and so become a part of the criminal enterprise.

But regardless of how the wealth is distributed, whenever money is loaned-at-interest, it creates in a ledger book the lie and the delusion that there is more money to be repaid than is actually in existence.

It was true in 3000 BC, and it is true today.

All the bankers will tell you as they arrogantly demand more payments on the credit card or home mortgage:

“Numbers do not lie.”

But what they don’t tell you is that liars who write numbers can make the numbers lie.

And all:

- bankers

- loan sharks

- financiers

and moneylenders are liars with the false numbers that they create.

The ancient money lenders discovered Secret Fraud #4 of the Sumerian Swindle:

“Loans of silver repaid with goods and not with silver, forfeit the collateral.”

But what if the bankers could make these loans to tens of thousands of Mesopotamians and then quietly withdraw the silver from circulation by keeping it hidden in their safe houses or shipping it to another country or to another city-state?

Once the loans had been made, once the clay contracts had been written, once the agreements were presented to the gods and confirmed by the scribes, the people were trapped.

By working in conspiring groups of moneylender guilds, the moneylenders could then claim both principle and interest in silver when there was not enough silver in circulation to pay off all agreements.

There was not enough silver in circulation because the moneylenders were hiding it in their strong boxes.

As subversive cartels, the moneylenders could become the owners of vast properties simply by hoarding enough silver so that there was not enough available for their debtors to make their payments.

Hoarding silver was easy to do since all of their silver they got for free.

These ancient moneylenders discovered the secret of using a commodity metal such as silver or gold as a form of money so that they could swindle the wealth of their fellow men simply by controlling the abundance or dearth of these commodity metals.

By stipulating repayment in silver, the amount of which was both limited in quantity and could be hoarded out of circulation, they were able to rake the wealth of the ancient Near East into their own barns and counting houses.

My simple example of two pieces of money and only one banker holds true even when the amount of money is in the trillions and the number of swindling bankers is in the tens of thousands as they are today.

But the swindle and fraud of these techniques are still the same.

Interest on a loan, even the tiniest interest in thousandths of one percent, still creates money on a ledger book that does not in reality exist.

And so, whether we are discussing two farmers in ancient Mesopotamia or the millions of indebted farmers and homeowners around the world today, they are still being swindled by the bankers and moneylenders who use sleight-of-hand arithmetical tricks to create the illusion that what you pay back must be more than what you borrow.

Was this “legal”?

Most of the traditions that were handed down to the people of Sumeria and Mesopotamia were just that, traditions.

In those days, there were no codified laws that everybody followed.

It was still a growing civilization of largely illiterate people who were led by literate thieves and swindlers who made their own rules as circumstances required.

It was a civilization of awilum [the Haves] who made it a part of their “tradition” to take whatever they could from the muskenum [the Have-Nots] and to profit by enslaving them to the loan-sharking rackets called “debt” and “interest-on-a-loan”.

If the defrauded peasant tried to get justice in the court system, he was in for a difficult time.

In the first place, there was no court system as in modern times but, rather, an informal court presided over by a judge without jury.

In Sumerian times, just as in modern times, the laws are as they “have always been”, written by the awilum [the Haves] to protect what they have and written entirely for their own benefit.

Edward Chiera (August 5, 1885 – June 20, 1933) was an Italian-American archaeologist, Assyriologist, and scholar of religions and linguistics.

In the Mesopotamian courts of law, as Edward Chiera, Professor of Assyriology at the University of Chicago, wrote:

“The loser must either pay a sum of money or become the slave of the winner until such time as he does pay.

It was a very dangerous proceeding for peasants to bring their grievances to court because their chance of obtaining justice was slight, and most of them ended by losing their freedom.

I have gone over these [cuneiform] contracts with great care, trying to find out whether the judges made any effort to apply the law and be wholly impartial.

Unfortunately, it is evident that they did not.

The wealthy landlords kept their records in good order for generations, and quite often could produce a document duly signed by many witnesses, which attested their right to ownership and thereby closed the case.

But the trouble was that the landlords had scribes of their own and a certain group of people who always acted as their witnesses.

There was nothing easier, in view of the fact that the peasants did not know how to read, than to juggle a few figures or to alter measurements; the mistake would not be discovered for many years.” [36]

But these were the cases where the cuneiform records clearly showed the consistently fraudulent and biased nature of the Mesopotamian “law courts”.

If the cuneiform records were not sufficiently precise or if they were not adequate enough for a moneylender to swindle the peasant’s property, then the moneylenders offered an ingenious swindle as an alternate choice.

To “prove” their innocence and “prove” their honest piety before the gods, they offered to acquiesce to the will of the gods, if the peasant would accept the river test.

A peasant could vow with the gods as his witness that the landlords and moneylenders were defrauding him.

Or he could vow with the gods as his witness that he was telling the truth and that the moneylenders were liars.

In such a case, he could claim his “right” to be subjected to the river test.

The event was timed with a water clock consisting of a clay bowl with a tiny hole in the bottom, slowing sinking in a larger bowl of water.

The peasant would be held underwater until the allotted time had passed, and his bowl had completely sunk.

If he didn’t drown during that time, then the gods had sided with him and the landlord would have to give back the property or the money that was swindled.

At first, this might seem somewhat fair.

The only problem was that the moneylenders controlled the size of the hole in the bottom of the bowl.

So, a bowl with a tiny hole was given for the peasant’s test.

And since they usually drowned as a result, the peasants soon learned that it was better to refuse to take the test.

Refusing the river test implied that they did not have the gods behind them and that the moneylender was right in taking their property.

It was an ingenious swindle in which the moneylenders were able to offer their own piety and trust in the gods as “proof”.

After all, they were willing to endure the river test, too, just as long as the peasant tried it first.

With the river test as “proof,” they could avoid accusations of fraud while stealing the lands of the muskenum [Have-Nots] even as the superstitious and god-fearing people looked on in wonder.

This “legal” system of Sumeria was never questioned by those who lived under its thrall simply because it had:

“always been here.”

The rich had always enslaved the poor since before the Sumerians had arrived from the South.

Money lending was a total fraud in every definition of the word, just as it is today.

But it is only in modern times, after all of these centuries filled with the:

- warfare

- starvation

- disease

purposely created by the moneylenders that we can ask:

“Just because it has always been here, does this mean that fraud, swindling and betrayal are legitimate ways for Mankind to follow?

If the rich got their wealth by stealing it from the poor, should they be allowed to keep it?”

The awilum [Haves] said,

“Yes, it is mine!”

and continued to enslave their fellow men with usury and deceit while the muskenum [Have Nots] never thought about it simply because money lending-at-interest has “always been here”.

Because it has “always been here,” no one has ever asked,

“Should it be allowed to continue?”

or

“Should the thieves be allowed to keep what they have stolen?”

or

“Why not hang the bankers and take back the wealth that they have stolen?”

The Lifeline of the Canal System

Without water, the crusty and dusty soil of Mesopotamia could never have grown the world’s first civilization.

The flood season of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers is between April and June, so it is not well-timed for planting.

Yet, through irrigation ditches and canals, the Two Rivers were made to irrigate thousands of square miles of barley and wheat and green gardens.

With a dependable and carefully regulated irrigation system, Mesopotamia thrived.

It was this dependence upon the regulated flow of water that was most responsible for the necessity of civil government.

Digging canals required well-ordered gangs of workers whose labor had to be evenly proportioned.

Their food rations had to be equally weighed and fairly distributed.

Proper amounts of water for each field had to be timed with the water clocks.

The volume of water for each field had to be calculated.

The canals and ditches had to be maintained against erosion and cleared of weed invasion.

All of this, plus the numerous:

- runners

- cooks

- suppliers

- carpenters

- rope-makers

- boatmen

and ancillary workers of all kinds, had to be efficiently organized and administered.

This was one of the major responsibilities of the city governments throughout Mesopotamia because without water and the resulting crops, everybody would die of starvation.

These life-giving waterways were also important for trade.

Indeed, trade was necessary for the very survival of these city-states because Mesopotamia lacked everything needed to build a civilization.

- Wood

- metal

- stone

could only be obtained from distant places either through trade or by military force.

And trade required transportation.

In ancient Mesopotamia, the most efficient way of transporting goods was by water.

Most places in Mesopotamia could be reached by the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers or along their tributary rivers and canals.

From the mouth of the Two Rivers, ships sailed down the Persian Gulf to Melukkha (the Indus Valley) and the East Arabian ports of Magan (Oman) and Dilmun (Bahrain).

From the western-most loop of the Euphrates, a relatively short donkey caravan could reach the Mediterranean Sea.

Again, civil administration was necessary to regulate this river traffic and to tax the cargos of the various merchants.

Controlling ship traffic had both an economic and military use.

So, the kings in every city took special interest in this work.

Trade by river was not some minor pastime by primitive aborigines in reed boats, as some modern readers might assume of the people of those ancient times.

It was a well-organized, sophisticated and hugely lucrative industrial enterprise from its earliest inception involving large networks of both wholesale and retail traders and their related suppliers and customers.

As an example of scale, Sumerian ships in the third millennium could hold about twenty-five tons and Babylonian ships in the first millennium about forty tons of cargo.

A cuneiform text mentions thirteen thousand minas (roughly seven tons) of copper as part of one ship’s cargo.

This was the goods of just one importer.

The metal came in ingots of up to four talents (about 200 pounds) shaped like a cowhide with legs at each of the corners so that it could be lifted and carried by four men.

In the earliest days of Sumeria, the merchants and tradesmen did their business with the temples as the main supplier of both export goods and the recipient of the imported items.

But as their wealth increased, the moneylenders and merchants became independent of any religious ties and worked for their own personal profits.

Boat captains, away for so long from their homeports, have always had an independent bent.

So, there were plenty of opportunities for the ships’ captains and the boatmen to form working alliances with the merchants who hired their services.

In this way, the merchants and moneylenders had close relationships with the ship captains.

The principal exports from Sumeria to Dilmun (Bahrain) were:

- garments

- grain

- oil

provided by private businessmen.

Contracts were drawn up, giving the value of the goods in terms of silver and stating the agreed silver value for Dilmun copper to be brought back by the return trade.

But there were some important differences between how the merchants and the moneylenders dealt with one another that depended upon whether transportation was by land or by ship.

In the caravan trade with Capadocia (Central Turkey), the moneylenders who were financing a trade agent were entitled to two-thirds of the total profits, with a guaranteed minimum return of 50 percent on his outlay and no risk to his capital.

On the other hand, in the sea trade to Dilmun (Bahrain), the entrepreneur normally received, instead of a share in the profits, a fixed return.

If the investor did become a full partner in the venture, he then shared the risks as well as any profits.

The more favorable conditions for the sea trader as against the caravan leader are related to the fact that the trade with Dilmun was a “closed shop”, admission to which was a matter of great difficulty; it needed technical skill to undertake the actual voyage, while it was necessary for the trader to have personal contacts on the island before he could trade there. [37]

In other words, from the earliest times, those who practiced international sea trade with:

- India

- Oman

- Bahrain

did so as a closed cartel of merchants and moneylenders who had a closer and more trusting relationship with one another than would be found in the more common kinds of business arrangements.

The Sumerian merchants and moneylenders formed cartels at a very early time and practiced monopoly finance.

Only those who were part of this elite in group were allowed to trade in the distant ports.

With ships, there was a great chance for loss of the cargo that could not be recovered if the ship sank or if a ship did not return because of piracy or even if the merchant and captain had decided to steal the cargo and immigrate to a foreign land.

With a missing ship, there was no way to know what had happened and no way to even know where to start looking for it.

So, better terms were given to the merchants who traveled by ship as an incentive for them to return.

But if a caravan did not return, there were ways of tracking it down, so heftier profits could be squeezed out of the caravan traders.

Once the trade goods arrived in Mesopotamia either by ship or by caravan, they were most easily transported throughout the region by the many boats that plied the canals and rivers.

The large numbers of boats of all sizes can be surmised from a single letter sent to the King of Ur by his governor Ibbi-Sin who had been sent to secure grain for the besieged city of Ur.

Ibbi-Sin (Sumerian: 𒀭𒄿𒉈𒀭𒂗𒍪, Di-bi₂-Dsuen), son of Shu-Sin, was king of Sumer and Akkad and last king of the Ur III dynasty, and reigned c. 2028–2004 BC (Middle chronology). During his reign, the Sumerian empire was attacked repeatedly by Amorites. As faith in Ibbi-Sin’s leadership failed, Elam declared its independence and began to raid as well. Ibbi-Sin ordered fortifications built at the important cities of Ur and Nippur, but these efforts were not enough to stop the raids or keep the empire unified. Cities throughout Ibbi-Sin’s empire fell away from a king who could not protect them, notably Isin under the Amorite ruler Ishbi-Erra. Ibbi-Sin was, by the end of his kingship, left with only the city of Ur. In 2004 or 1940 BCE, the Elamites, along with “tribesmen from the region of Shimashki in the Zagros Mountains” sacked Ur and took Ibbi-Sin captive; he was taken to the city of Elam where he was imprisoned and, at an unknown date, died.

Ibbi-Sin acquired the necessary grain but sent a letter to Ur asking for six hundred boats of one hundred twenty gur each, that is, of holding a capacity of about 186,807 barrels.

Thus, when thinking about the amounts of goods and wealth that flowed through Mesopotamia, one should not think in terms of a few donkeys with packs but, rather, of huge amounts of wholesale and retail goods, comparable in ratio though on a smaller scale, to the goods flowing through a modern seaport.

We are studying here a sophisticated society, not merely an ancient one.

The greed of the moneylenders was just as voracious as today but with fewer restrictions.

From the very earliest times, the Treasonous Class had learned how to increase their profits by restricting the flow of goods.

Certainly, they did not like to pay taxes to the kings or the tribal chiefs through whose lands their caravans had to pass.

Taxes meant higher prices to their customers.

There was only so much their customers were willing to pay so higher prices reduced sales and ate into their profit margins.

Transportation costs were always a problem since the multitudes of boatmen were free to charge whatever they wanted for shipping.

And so, to control these problems, the merchants organized the river traffic into guilds of boatmen who controlled all of the shipping fees.

This form of monopoly allowed the merchants to further squeeze the small farmers.

The boatmen could charge the poor people a higher price to ship their produce than they would charge the bigger merchants who gave them more work though at a lower price per trip.

Through such cartels, the merchants saved money, the boatmen made more money, and the poor peasants were further impoverished.

Because poor people always suffer the most from high prices, when the economy became too difficult for the poor, they easily fell into the clutches of the moneylenders who swindled them out of:

- their farms

- their families

- their freedom

Through monopoly of wholesale imports and distribution channels, the Treasonous Class learned how to gain more wealth for themselves simply by getting control of the choke points in the trade routes.

They perfected Secret Fraud #21:

“Control the choke points and master the body; strangle the choke points and kill the body.”

These Sumerian tamkarum [merchant-moneylenders] learned how to make more money by monopolizing transportation and raising prices as well as profiting from the ripple effect of a slowly spreading poverty.

By the time the Assyrians took control of Mesopotamia, the Sumerian word for “boatman” had become the same as the word for “thief”.

Thus, the Treasonous Class corrupted the boatmen who were a vital part of civilization.

Trade in Metals

Just as in modern times, the trade in metals was done on an industrial scale.

There was no room for the small merchant except as an agent of the big wholesalers or for the small-time peddler of finished goods loaning a few shekels to the local yokels.

Importing of metals was a field open only to the wealthiest of citizens.

These citizens were the kings, the temples, and the tamkarum [merchant- moneylenders].

Because metals were so vital to both the civilian economy and to the military, those who dealt in these commodities could only be the awilum [the Haves].

Because Mesopotamia did not have any metals in the region, everything had to be imported.

Of course, all metals are very heavy and whether you import the raw ore and smelt it yourself or import metallic ingots, you need lots of labor in the form of:

- miners

- laborers

- donkeys

- carts

- ships

- boats

tool and weapon craftsmen, and mid-level merchants to get it to market.

Thus, the commodity metal dealers were among the wealthiest of the awilum [Haves].

It was a closed society that included among its members the kings, top temple priests, the moneylenders and the richest merchants.

Everyone else were either loyal subalterns, minor partners or employees who worked for them.

By 2900 BC, copper was in common use as:

- vases

- bowls

- mirrors

- cosmetic pots

- fishhooks

- chisels

- daggers

- hoes

and axes.

Copper ingots were shipped both overland from the Iranian plateau or by ship on the Persian Gulf from Magan (Oman) and Melukhkha (the Indus Valley).

Analysis of copper and bronze objects of this period show that in Sumerian times it was the surface ores which were used and not the deeper lying ones (which occur as sulphides); thus no deep mining was involved.

Iron of meteoric origin began to be used from 3000 BC onwards mainly in beads and trinkets because it was too brittle to be useful for much else.

It wasn’t until after 1500 BC, when the Hittites discovered that iron could be made into steel by the process that we know as carbonizing, which was achieved by the blacksmith who repeatedly hammered the glowing iron that had been heated on a fire of glowing charcoal.

This new technique gradually spread throughout the Near East and came into use in Mesopotamia from about 1300 BC. [38]

But in all of these centuries, the metallic trade was carried out only by the rich and the powerful.

- Copper

- bronze

- zinc

- lead

- iron

- silver and gold

all had both commercial and military uses.

But it was not the hard and useful metals that drove the machinery of commerce and war, it was the soft and useless metals like gold and silver that drove the moneylenders mad.

With small amounts of silver and gold, they could buy everything on earth including the bodies and souls of Men.

TRANSMIGRATION: SOULS: The Jewish Soul VS. the Gentile Soul – Library of Rickandria

The moneylenders discovered Secret #5 of the Sumerian Swindle:

“The debtor is the slave of the lender.”

Therefore, to enslave the world, the moneylenders merely needed to put everyone into debt.

CONTINUE

BOOK: The Sumerian Swindle: How the Jews Betrayed Mankind – Vol. 1 of 3 – Library of Rickandria

The Sumerian Swindle: How the Jews Betrayed Mankind – Chapter 5: Daily Life in Sumeria