Chapter 1: The Genesis of Zionism: Early Ideologies and Influences

This chapter explores the historical context and intellectual origins of Zionism, tracing its roots in European Jewish history and the rise of antisemitism.

It introduces key early Zionist thinkers and their vision for a Jewish homeland.

Early Zionist Thought and the Rise of Nationalism

This subsection will examine the intellectual and socio-political climate that fostered the emergence of Zionist thought in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It will analyze the impact of antisemitism in Europe, the rise of nationalism, and the influence of various intellectual currents on the development of Zionist ideology.

Specific examples of early Zionist thinkers and their contributions will be explored, highlighting their differing visions for a Jewish homeland.

The historical context of pogroms and discrimination will be detailed.

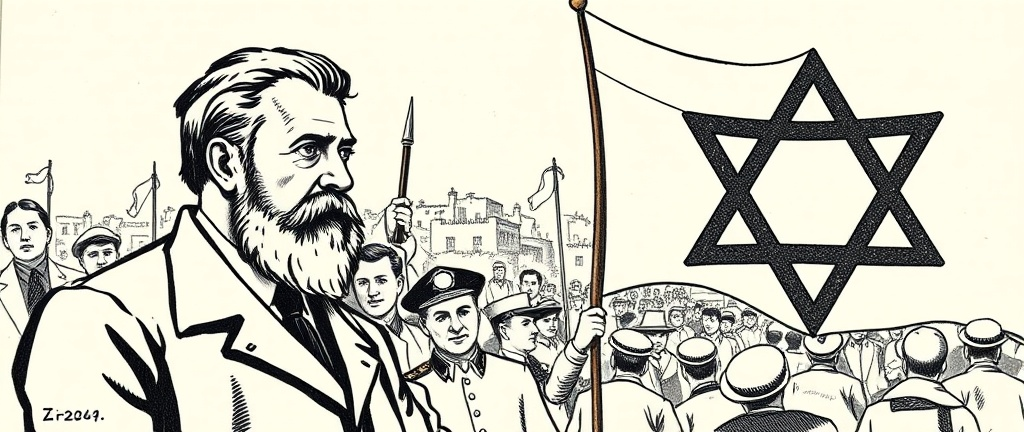

Theodor Herzl and the First Zionist Congress

This section focuses on the pivotal role of Theodor Herzl in shaping the Zionist movement.

It will analyze Herzl’s political strategy, his negotiations with various European powers, and the significance of the First Zionist Congress in 1897.

The section will also explore the diverse opinions and factions within the early Zionist movement, highlighting their debates and differing approaches.

Key figures involved in the First Zionist Congress will be introduced.

Early Zionist Settlements in Palestine: Challenges and Successes

This subsection will examine the early efforts to establish Jewish settlements in Palestine, highlighting the challenges faced by the pioneers, including land acquisition, relations with the local Arab population, and the logistical difficulties of establishing self-sufficient communities.

The successes and failures of these early settlements will be analyzed, setting the stage for later developments.

Examples of specific settlements and their histories will be provided.

The Balfour Declaration and its Implications

This subsection analyzes the significance of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, examining its context, its promises, and its immediate and long-term impact on the Zionist movement.

The section will delve into the debates surrounding the Declaration, exploring the perspectives of various stakeholders and the complexities of reconciling competing claims to Palestine.

The political landscape of the time will be examined.

World War I and the Transformation of the Zionist Landscape

This subsection will analyze the impact of World War I on the Zionist movement.

Miles Williams Mathis: Archduke Franz Ferdinand – Library of Rickandria

It will explore the role of Zionists in the war effort, their relationships with various Allied powers, and the shifting political dynamics in the region.

Specific instances of how the war affected Zionist activities and strategies will be presented.

The changes to the political climate in the aftermath of the war will be thoroughly analyzed.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a confluence of factors that gave rise to Zionist thought, a complex ideology that sought to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Understanding this genesis requires examining the broader socio-political landscape of the time, particularly the pervasive antisemitism in Europe, the burgeoning tide of nationalism sweeping across the continent, and the intellectual currents that shaped the thinking of early Zionist pioneers.

These factors, intertwined and mutually reinforcing, provided the fertile ground from which Zionist ideology sprouted.

Antisemitism, a persistent and virulent strain in European history, reached a fever pitch in the late 19th century.

RICHEST in 19th Century – Library of Rickandria

While Jews had faced discrimination for centuries, the latter half of the 19th century saw a rise in organized, systematic persecution.

This was fueled by a variety of factors, including economic anxieties, religious prejudice, and the scapegoating of Jews for societal ills.

The Dreyfus Affair in France, a case of a Jewish army officer falsely accused of treason, became a potent symbol of the pervasive anti-Jewish sentiment.

Miles Williams Mathis: J’accuse…! Part Deux: The Dreyfus Affair on Trial – Library of Rickandria

The affair, despite its eventual resolution in Dreyfus’s favor, exposed the deep-seated prejudice within French society and resonated across Europe.

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the French Third Republic when he was wrongfully accused and convicted of being a German spy due to antisemitism. Dreyfus was arrested, cashiered from the French army and imprisoned on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. Eventually, evidence emerged showing that Dreyfus was innocent and the true culprit was fellow officer Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy.

Similar incidents of state-sponsored or tolerated persecution, ranging from legal discrimination to violent pogroms, occurred throughout Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

These pogroms, often characterized by widespread:

- violence

- looting

- murder

forced many Jews to contemplate the precariousness of their existence in Europe and seek alternatives.

The sheer brutality and frequency of these events provided a powerful impetus for those seeking a more secure future for the Jewish people.

WHO ARE THE MODERN JEWS? – Library of Rickandria

The rise of nationalism across Europe also played a crucial role in shaping Zionist thought.

Nationalism, an ideology emphasizing the importance of national identity and self-determination, was sweeping across the continent, leading to the unification of previously disparate territories and the assertion of national interests on a global stage.

This rise of national consciousness had a profound impact on Jewish intellectuals who grappled with the question of Jewish identity in a world increasingly defined by national borders and allegiances.

While many Jews had integrated into European societies, the persistent antisemitism they faced underscored the limitations of assimilation and highlighted the lack of a secure, universally recognized Jewish nation-state.

Zionism offered a solution: to create a Jewish nation-state based on the principle of national self-determination, a principle that was resonating strongly across Europe at the time.

The intellectual currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries further contributed to the development of Zionist ideology.

Influenced by Enlightenment ideals of reason and progress, early Zionist thinkers such as Moses Hess, considered one of the founders of socialist Zionism, sought to create a society that balanced individual liberty with communal responsibility.

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early socialist and Zionist thinker. His theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zionism.

Hess’s work, “Rome and Jerusalem,” published in 1862, laid out a vision of a Jewish state where socialist principles would be central.

Rome and Jerusalem – Anna’s Archive

His emphasis on collective ownership and cooperative labor influenced the early kibbutzim, collective agricultural settlements that would later become a significant feature of Israeli society.

Simultaneously, other thinkers, such as Theodor Herzl, embraced a more pragmatic and political approach to Zionism.

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the Zionist Organization and promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine in an effort to form a Jewish state. Due to his Zionist work, he is known in Hebrew as Chozeh HaMedinah (חוֹזֵה הַמְדִינָה), lit. ‘Visionary of the State’. He is specifically mentioned in the Israeli Declaration of Independence and is officially referred to as “the spiritual father of the Jewish State”.

Herzl, a journalist and playwright, witnessed the antisemitism firsthand and saw the establishment of a Jewish state not merely as a solution to anti-Semitism, but as a matter of necessity.

His seminal work, Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State“), published in 1896, became the founding document of modern political Zionism.

The Jewish State – Anna’s Archive

Herzl’s political acumen and organizational skills were instrumental in galvanizing the Zionist movement and bringing together diverse groups under a common goal.

The contrasting views between the utopian socialist visions of Hess and the pragmatic political strategies of Herzl represent the spectrum of thought within early Zionism.

It should be noted, this spectrum was significantly broader still, encompassing religious Zionists who viewed the establishment of a Jewish state as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, and secular Zionists who prioritized the political and practical aspects of nation-building.

This confluence of:

- antisemitism

- nationalism

- intellectual

ferment shaped the early Zionist thought and gave birth to a movement that would profoundly impact the Middle East and the world.

The widespread discrimination and persecution that Jews faced in Europe, coupled with the rise of national consciousness across the continent, created a climate where the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine gained significant traction.

The intellectual contributions of diverse thinkers, such as Hess and Herzl, offered various pathways to achieving this goal, shaping the ideology and strategy of the movement.

The historical context of pogroms, discrimination, and the limitations of assimilation cannot be overstated in understanding the urgency that propelled the early Zionist movement.

The yearning for self-determination, a concept central to the rising nationalist sentiments across Europe, formed the bedrock of Zionist aspiration.

The belief in a secure future for the Jewish people, free from the ever-present threat of persecution, was the fundamental driving force behind this powerful ideology.

It was this combination of forces that not only fostered the emergence of Zionist thought but also propelled it towards becoming a powerful political movement.

The differing visions of early Zionist thinkers, ranging from socialist utopias to pragmatic political strategies, reflected the multifaceted nature of Jewish identity and the complex challenges faced by those seeking to create a national home.

These differences, while creating internal tensions within the movement, also contributed to the development of various Zionist factions and approaches.

The early Zionist movement was far from monolithic, encompassing a range of ideologies and strategies that debated over the best path forward.

Understanding these nuances is critical to a comprehensive appreciation of the movement’s evolution and its impact.

The early years were characterized by vigorous internal debates, where differing political, economic, and religious philosophies played significant roles in shaping the movement’s agenda.

These debates, often passionate and sometimes divisive, helped to refine and clarify the Zionist vision as the movement gained momentum.

These internal dynamics provided the impetus for constant adaptation and evolution, a characteristic that would define the Zionist project in the years to come.

The early Zionist movement was far from a monolithic entity, its diversity a testament to the complexity of the cause and the diverse individuals who dedicated themselves to its success.

The impact of these early ideologies extended far beyond the intellectual sphere.

Early Zionist settlements in Palestine, despite facing numerous challenges, represented the tangible manifestation of Zionist ideals.

The establishment of these settlements demonstrated the determination of early Zionists to translate their vision into a reality.

They struggled with issues such as land acquisition, often facing resistance from the local Arab population.

The logistical difficulties of establishing self-sufficient communities in a relatively underdeveloped region also presented formidable challenges.

The early settlers, often pioneers who faced hardship and deprivation, played a critical role in laying the foundation for the later development of the state of Israel.

The experience of these early settlements, highlighting both their successes and their failures, served as a vital learning curve for the Zionist movement, shaping its strategies and approaches in the years to come.

These successes and failures would inform the movement’s strategy, leading to adjustments and refinements in their approach to settlement and land acquisition.

The early Zionist movement’s efforts to establish a secure future for the Jewish people was a complex undertaking, shaped by a unique combination of factors.

The pervasive antisemitism in Europe, coupled with the rise of nationalism and influential intellectual currents, created the environment for Zionist thought to flourish.

The divergent views within the movement, from utopian socialist visions to pragmatic political strategies, resulted in a dynamic and adaptable approach to achieving the establishment of a Jewish homeland.

The challenges faced by the early Zionist settlers in Palestine, despite the hardships, provided valuable lessons for the movement’s future development.

Understanding these intricate and multifaceted factors is crucial to grasping the genesis and evolution of Zionism.

The next chapters will delve into the critical turning points and defining moments that shaped the course of the Zionist movement, further clarifying the complex history of this pivotal movement.

Theodor Herzl, a Viennese journalist and playwright, stands as a pivotal figure in the transition of Zionism from a nascent intellectual current to a powerful political movement.

Unlike earlier Zionist thinkers who focused primarily on philosophical or religious arguments for a Jewish homeland, Herzl adopted a pragmatic, political approach.

His seminal work, Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State,” 1896), didn’t merely offer a utopian vision; it presented a concrete plan for establishing a Jewish state through diplomatic negotiation and international recognition.

Herzl, a keen observer of European politics, recognized the limitations of assimilation in the face of escalating antisemitism.

He witnessed firsthand the virulent prejudice, the societal scapegoating, and the precariousness of Jewish life in Europe.

The Dreyfus Affair, the infamous case of a falsely accused Jewish officer in France, deeply impacted him, solidifying his belief in the necessity of a Jewish state as the ultimate solution to the “Jewish problem.”

Herzl’s approach differed significantly from the earlier, more idealistic visions.

While thinkers like Moses Hess emphasized socialist principles and communal living in their vision of a Jewish state, Herzl focused on the political realities.

He believed that securing international support and negotiating with world powers was crucial to the success of the Zionist project.

He didn’t shy away from the complexities of realpolitik, understanding the need to navigate the intricate web of European diplomacy.

This pragmatism, however, didn’t come at the expense of his unwavering commitment to the Jewish cause.

He understood that the establishment of a Jewish state wasn’t simply a matter of establishing a new community, but of creating a secure and sovereign nation for the Jewish people, protected from the persistent threat of persecution.

Herzl’s political acumen extended beyond mere theorizing.

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 1859 – 4 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty‘s 300-year rule of Prussia.

He embarked on a series of high-profile meetings with key European figures, including Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and various officials in:

- France

- Britain

- the Ottoman Empire

While these efforts yielded limited immediate success, they were crucial in raising the profile of Zionism and planting the seeds for future negotiations.

He sought not only to persuade these powerful leaders of the merits of a Jewish homeland but also to explore potential locations, with Palestine emerging as the preferred choice due to its historical and religious significance for Jews.

The meetings also highlighted the obstacles to be overcome, such as the existing population in Palestine, the complexities of international relations, and the resistance of various political and religious interests.

Herzl’s tireless efforts culminated in the First Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland, in August 1897.

This event marked a watershed moment in the history of Zionism, solidifying it as a formally organized movement with clear goals and strategies.

The Congress, attended by nearly 200 delegates representing various Jewish communities across Europe and beyond, was not merely a gathering of like-minded individuals; it was a carefully orchestrated event that showcased Herzl’s exceptional leadership and organizational abilities.

He had successfully managed to bring together diverse Jewish groups – from religious Zionists who viewed a Jewish homeland as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, to secular Zionists who focused on the political and practical aspects – under a common banner.

The Basel Program, adopted at the Congress, laid out the fundamental objectives of the Zionist movement.

It declared the goal of creating a legally secured homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine.

This declaration was a significant departure from earlier discussions, which often lacked clear political goals and tended towards more philosophical or communal aspirations.

The program, however, also reflected the inherent complexities within the Zionist movement.

While aiming for a concrete political goal, it acknowledged the need for a phased approach, recognizing the challenges involved in establishing a Jewish state in a region already inhabited by a significant Arab population.

This recognition, though perhaps implicit, underscored the long-term and complex nature of the project and demonstrated an awareness of the potential conflicts that would inevitably arise.

The First Zionist Congress also highlighted the diverse viewpoints within the nascent movement.

While Herzl played a dominant role, he wasn’t the only influential figure.

Representatives from various Jewish communities across Europe brought their unique perspectives and experiences to the Congress, leading to vibrant discussions and, at times, heated debates.

These early debates, though often characterized by a strong emphasis on unity in the pursuit of the common goal of a Jewish homeland, set the stage for the emergence of different factions within the Zionist movement in later years.

These factions, with their varying ideologies and strategies, would play a significant role in shaping the future of Zionism, sometimes collaborating, sometimes competing for influence, and at times, even clashing.

For example, the Congress witnessed significant discussion on the nature and character of the future Jewish state.

While some advocated for a socialist model mirroring the kibbutzim – collectivist agricultural settlements already establishing themselves in Palestine – others promoted a more capitalist approach to economic development.

The question of land acquisition also sparked lively debates.

Some favored gradual purchase of land from existing landowners, while others advocated for a more aggressive, even confrontational approach.

These early disagreements, though reflective of the varied backgrounds and perspectives of the delegates, contributed to the development of different Zionist factions in subsequent years, shaping the movement’s tactics and overall trajectory.

The range of opinions demonstrated the movement’s dynamic nature and its capacity for internal debate.

Furthermore, the Congress addressed the crucial issue of obtaining international support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland.

Herzl’s emphasis on diplomatic efforts found resonance with many delegates, but others questioned the viability of solely relying on diplomacy.

They emphasized the importance of self-reliance and the need for Jewish communities to prepare themselves for the challenges of establishing and defending a new nation in Palestine.

These varying approaches to the practical aspects of state-building would fuel internal discussions within the movement for years to come.

The pragmatic approach taken at the First Zionist Congress, however, reflected a realistic acknowledgement of the need to navigate both international diplomacy and the practical realities of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine.

The First Zionist Congress wasn’t a utopian gathering that magically resolved all disagreements or provided seamless solutions to the complex political challenges ahead.

Instead, it served as a foundational moment, laying the groundwork for the future activities of the Zionist movement.

It established the structure for ongoing organization, enabling the movement to grow, adapt, and respond to evolving circumstances and internal debates.

The congress represented a pivotal step in the transformation of Zionism from an abstract idea to a focused, organized political movement with concrete objectives.

The Congress’s legacy extended beyond the adoption of the Basel Program.

It fostered a sense of collective identity and purpose amongst the diverse Jewish communities represented, demonstrating the potential for unity in the face of shared adversity.

Herzl’s exceptional leadership played a key role in fostering this sense of unity and shared purpose.

The event’s significance lies not just in its immediate outcomes but in its contribution to the ongoing development and evolution of Zionist ideology and strategy in the years to come.

It was a turning point that launched the Zionist movement into a sustained period of intense activity, marked by a gradual but steady progress towards the eventual establishment of the State of Israel.

This organizational success was a testament to Herzl’s leadership and the inherent resilience of the Zionist movement.

The congress laid the foundational structure for the complex and multifaceted journey that lay ahead.

The subsequent chapters will delve deeper into these subsequent developments, examining the evolution of Zionist strategy, its internal conflicts, and its impact on the region and global politics.

The First Zionist Congress, while a monumental achievement in solidifying the Zionist movement, marked only the beginning of a long and arduous journey.

The theoretical blueprint for a Jewish homeland in Palestine now needed to be translated into a tangible reality on the ground.

This involved the challenging task of establishing settlements in a land already inhabited, necessitating intricate negotiations, resource management, and the creation of self-sustaining communities amidst unfamiliar landscapes and pre-existing social structures.

The early Zionist settlements in Palestine represent a microcosm of the movement’s overall endeavor: a mix of remarkable achievements and significant setbacks, constantly shaped by the interplay of ideology, pragmatism, and the realities of the existing environment.

The acquisition of land proved to be one of the most significant hurdles.

Palestine, under Ottoman rule, possessed a complex land tenure system.

Securing land legally required navigating bureaucratic processes, often fraught with delays and uncertainties.

Furthermore, many plots were already owned by Arab families, leading to inevitable negotiations and potential conflicts.

The Zionist Organization employed various strategies, from direct purchase to leasing agreements, depending on the specific circumstances and available resources.

Often, the prices paid were inflated due to the high demand and the strategic significance of certain locations.

This naturally engendered resentment amongst some segments of the Arab population, who saw the land purchases as a threat to their own economic security and a potential precursor to broader displacement.

These transactions were not always smooth and often became flashpoints of tension, highlighting the complex socio-political realities the nascent settlements were attempting to navigate.

The early settlers themselves, often dubbed “pioneers” or “chalutzim,” were a diverse group, hailing from different backgrounds and possessing varying levels of experience in agriculture and community building.

Many were idealistic young people from Europe, drawn to the vision of creating a new life in a historic homeland.

Their skills and resources varied, leading to unequal distribution of resources and challenges in ensuring collective prosperity within the burgeoning communities.

Some settlements, like Rishon LeZion, established in 1882, prioritized agricultural development, focusing on wine production and citrus farming.

Others, like Petach Tikva, founded in 1878, grappled with harsh environmental conditions and struggled with water scarcity and disease.

The successes and failures of these early ventures were not just a matter of individual initiative; they were deeply intertwined with the broader socio-economic and political context.

The relationship with the existing Arab population was another critical factor.

While some interactions were cooperative, others were fraught with conflict.

Competition over land and resources inevitably led to tensions, often exacerbated by differing cultural norms and linguistic barriers.

Misunderstandings and misinterpretations fueled mutual distrust, hindering collaboration and creating an atmosphere of suspicion and hostility.

The Zionist movement, in its early phases, often displayed a naive understanding of the complexities of the local Arab society and its historical grievances.

This lack of cultural sensitivity, coupled with the perceived threat of land encroachment, contributed to considerable friction between the Jewish and Arab communities.

Historians debate the extent to which these conflicts were inevitable or the result of specific policies and actions.

Some argue that early Zionist leaders could have adopted more conciliatory approaches, while others stress the inherent difficulties of reconciling two distinct national aspirations within a limited geographical area.

The logistical challenges were immense.

The settlers faced shortages of water, adequate housing, and healthcare facilities.

Establishing reliable infrastructure, including transportation networks and communication systems, proved to be a slow and arduous process.

The harsh climate, particularly during the arid summer months, posed a serious threat to the survival of the settlements.

Diseases such as malaria were rampant, claiming many lives, and adding a layer of difficulty to an already precarious existence.

Malaria’s impact, for instance, disproportionately affected the agricultural settlements, underscoring the need for infrastructural development and healthcare systems that could adequately support a growing population.

This lack of basic infrastructure further complicated matters and highlighted the importance of logistical planning and community resilience in the face of unexpected adversity.

Despite the numerous obstacles, the early Zionist settlements demonstrated remarkable resilience and resourcefulness.

The settlers showed an unwavering commitment to their vision, overcoming seemingly insurmountable difficulties through collective efforts and mutual support.

The kibbutzim, collective agricultural settlements, emerged as a powerful example of this communal spirit and organizational capacity.

These communities, based on shared ownership of resources and collective labor, demonstrated that self-sufficiency and economic sustainability were attainable, even in challenging circumstances.

Their model of communal living, emphasizing cooperation and social equality, offered a powerful counterpoint to the existing social and economic structures in Palestine.

The success of certain settlements became models of development for others.

Lessons learned from failures were meticulously analyzed, informing future strategies and approaches.

The gradual expansion and consolidation of settlements were facilitated by improved transportation networks, better access to resources, and, crucially, growing financial support from Jewish communities worldwide.

The collective effort of raising funds and coordinating support demonstrated the strength of the global Zionist network in providing essential backing to its endeavors in Palestine.

However, as settlements expanded, so did the interactions with the indigenous population, and the initial interactions and their impact would have long-lasting consequences.

The early Zionist settlements in Palestine, therefore, present a multifaceted narrative.

They represent a story of perseverance and ingenuity, of overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles through collective action and unwavering dedication.

The challenges faced—land acquisition, relations with the local Arab population, and the logistical difficulties of establishing self-sufficient communities—were significant, and the responses to these challenges were often uneven and inconsistent.

But they also highlight the complexities of establishing a new society in an already-populated region, and the tensions inherent in reconciling competing national aspirations.

The successes and failures of these early settlements were crucial in shaping the subsequent development of the Zionist movement, laying the groundwork for the more extensive and politically charged events that would follow.

The experiences of these early settlers, their triumphs and struggles, serve as a vital prelude to the more complex and often contentious history that was to unfold.

These experiences would permanently shape the trajectory of Zionism, influencing subsequent strategies, policies, and ultimately, the very formation of the State of Israel.

The seeds of both success and conflict were sown in this fertile, yet often turbulent, ground.

The year 1917 witnessed a pivotal moment in the history of Zionism with the issuance of the Balfour Declaration.

This seemingly brief document, penned by British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, would have profound and lasting consequences, shaping the trajectory of the Zionist project and setting the stage for decades of conflict in Palestine.

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (/ˈbælfər, -fɔːr/; 25 July 1848 – 19 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the Lloyd George ministry, he issued the Balfour Declaration of 1917 on behalf of the cabinet, which supported a “home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

The Declaration, in its entirety, was a surprisingly concise statement:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The seemingly simple language of the Declaration masked a complex web of political calculations and strategic considerations.

World War I was raging, and Britain, locked in a bitter struggle against the Ottoman Empire, sought to secure alliances and bolster its standing in the Middle East.

The promise of a Jewish homeland in Palestine was viewed as a means to garner support from Jewish communities across the globe, particularly in the United States, a significant source of financial and political influence.

Simultaneously, Britain sought to cultivate relationships with Arab leaders, promising them independence after the war, a pledge that directly contradicted the implications of the Balfour Declaration.

This inherent contradiction, a hallmark of British imperial policy at the time, would sow the seeds of future conflicts.

The Declaration’s impact on the Zionist movement was immediate and electrifying.

It offered, for the first time, a seemingly official sanction for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, providing a powerful boost to Zionist aspirations and galvanizing efforts to establish a presence in Palestine.

This newfound legitimacy emboldened Zionist leaders and spurred increased immigration to Palestine, leading to a dramatic increase in the Jewish population.

However, this influx of Jewish settlers also exacerbated existing tensions with the Arab population, who viewed the Balfour Declaration as a betrayal of their own aspirations for self-determination.

The promise of a “national home” was inherently ambiguous, leaving much room for interpretation and fueling disagreements regarding its scope and meaning.

The “national home” concept itself was a subject of considerable debate within the Zionist movement.

While some envisioned a fully independent Jewish state, others favored a more autonomous region within a larger framework.

The Declaration’s phrasing intentionally left this crucial aspect undefined, reflecting the British government’s own desire to maintain flexibility and avoid alienating either the Zionist or Arab populations.

This lack of clarity, however, would prove to be a major source of contention in the years to come, ultimately contributing to the eruption of violent conflict.

The reaction of the Arab world to the Balfour Declaration was swift and overwhelmingly negative.

Arab leaders and intellectuals viewed the Declaration as a blatant disregard for their rights and aspirations.

They perceived the promise of a Jewish homeland as a threat to their own national identity and territorial integrity, fueling resentment and opposition to British rule.

The Declaration fundamentally contradicted the promises made to Arab leaders regarding post-war independence and self-determination, creating deep mistrust and fueling nationalist sentiments throughout the region.

The perception of a Western power actively supporting Jewish immigration at the expense of the Arab population ignited anti-Zionist sentiment and laid the groundwork for future conflicts.

The immediate aftermath of the Balfour Declaration was characterized by increased Jewish immigration to Palestine, a surge in land purchases, and a growing sense of both hope and apprehension among Jewish settlers.

The influx of immigrants strained resources, fueled competition over land, and exacerbated tensions with the existing Arab population.

The British administration, burdened by the conflicting promises made to both Jews and Arabs, struggled to maintain order and navigate the increasingly complex political landscape.

This struggle played out in a series of localized conflicts, riots, and escalating tensions that would ultimately overshadow the initial optimism surrounding the Balfour Declaration.

Furthermore, the implications of the Balfour Declaration extended far beyond Palestine’s borders.

The Declaration’s existence and the subsequent events in Palestine heavily influenced the development of anti-Semitic narratives and provided ammunition to those who viewed the Zionist project as a threat to global stability.

Propaganda campaigns highlighting the perceived injustices inflicted upon the Arab population by Jewish settlers were widely circulated, tapping into existing prejudices and fostering anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic sentiments.

The Balfour Declaration became a powerful symbol in the larger context of inter-religious and inter-ethnic tensions, further complicating the already delicate situation in Palestine.

The legacy of the Balfour Declaration continues to resonate today.

Its ambiguities and contradictions contributed to decades of conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine, ultimately shaping the events that led to the establishment of the State of Israel and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The Declaration’s impact is not simply limited to the political arena; it continues to provoke intense debate and interpretation regarding the nature of national self-determination, the ethics of colonialism, and the complexities of religious and ethnic identity in a volatile region.

The document serves as a powerful reminder of the unintended consequences of political maneuvering and the lasting impact of seemingly brief pronouncements made amidst the heat of geopolitical conflict.

It highlighted, as well, the difficulties of forging a stable peace when competing claims to land and identity collide.

It exemplifies the challenges of applying abstract political ideals to a real-world environment marked by deep-seated historical tensions and complex social dynamics.

The Balfour Declaration’s lasting impact is undeniable.

It became a cornerstone of the Zionist narrative, a testament to international recognition of Jewish aspirations for self-determination.

However, this recognition came at a cost, setting in motion a chain of events that continue to shape the Middle East today.

The Declaration’s inherent ambiguity, its failure to fully address the concerns of the Arab population, and the broader context of British imperial ambitions all contributed to a legacy of conflict and mistrust.

Its study remains crucial for understanding the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the enduring challenges of resolving competing national claims in a region marked by historical grievances and profound cultural differences.

The Balfour Declaration, therefore, stands as a pivotal, yet profoundly problematic, turning point in the history of both Zionism and the Middle East.

Its legacy continues to resonate, serving as a stark reminder of the fragility of peace and the enduring consequences of political decisions made in times of war and uncertainty.

The unresolved issues stemming from its ambiguous promises continue to cast a long shadow on the region and underline the complexities inherent in attempting to reconcile competing national aspirations in a limited geographical space.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly reshaped the Zionist landscape, presenting both unprecedented challenges and unexpected opportunities.

Prior to the war, the Zionist movement, though gaining momentum, was largely a political and ideological project operating within the confines of the existing Ottoman Empire.

The war, however, dramatically altered the geopolitical map of the Middle East, creating a power vacuum that Zionist leaders sought to exploit.

The Ottoman Empire, weakened and increasingly embroiled in the conflict, proved less capable of suppressing Zionist activities within its territories.

The war effort itself saw Zionists actively involved, albeit in varying capacities and with complex motivations.

Many Zionist leaders, recognizing the potential benefits of aligning with Allied powers, actively supported the war effort, hoping to leverage their support to advance Zionist goals.

This involved various activities, including intelligence gathering, propaganda dissemination, and even military service.

The Zionist Organization, under the leadership of Chaim Weizmann, engaged in extensive negotiations with British officials, emphasizing the strategic advantages of securing Jewish support for the war.

Chaim Azriel Weizmann (/ˈkaɪm ˈwaɪtsmən/ KYME WYTE-smən; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the Zionist Organization and later as the first president of Israel. He was elected on 16 February 1949, and served until his death in 1952. Weizmann was instrumental in obtaining the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and convincing the United States government to recognize the newly formed State of Israel in 1948.

Weizmann’s scientific expertise proved particularly valuable, and his personal relationship with key British figures, cultivated over several years, proved crucial in securing the movement’s favor.

The British, locked in a fierce struggle against the Ottomans, recognized the potential benefits of enlisting the support of Jewish communities worldwide.

Jewish communities in America, particularly, held considerable financial and political influence, and Britain eagerly sought to harness this power for the war effort.

The promise of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, therefore, served as a powerful tool for securing this support, positioning the Balfour Declaration not merely as an act of humanitarianism or self-determination, but as a shrewd strategic maneuver in the midst of a global war.

The clandestine nature of many of these negotiations, however, underscores the complex and sometimes morally ambiguous nature of the alliances forged during this period.

The war also presented a significant logistical challenge for the Zionist movement. Communication lines were disrupted, movement within Palestine was restricted, and many Zionist activists found themselves caught in the crossfire between belligerent forces.

This impacted organizational efforts, fundraising campaigns, and the overall momentum of Zionist immigration to Palestine.

Yet, ironically, these wartime disruptions also created a space for more covert and independent actions, sometimes undertaken with minimal oversight from the central Zionist leadership.

The relationship between Zionists and other Allied powers varied.

France, another significant player in the Middle Eastern theater of war, also maintained a complex relationship with the Zionist movement.

While France wasn’t as directly involved in facilitating Zionist immigration to Palestine to the same extent as Britain, French colonial ambitions in the region, coupled with strategic concerns, sometimes led them to support Zionist initiatives which they saw as aligning with their overall geopolitical interests.

The relationship, however, was significantly less explicit or supportive than Britain’s, often characterized by a greater degree of cautious engagement.

This ambiguity often left Zionist leaders navigating a precarious terrain, needing to secure the support of different Allied powers without jeopardizing their overall strategy or creating conflict between their various backers.

The shifting political dynamics of the region during and after the war dramatically influenced Zionist aspirations.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent mandate system introduced by the League of Nations provided a framework for the implementation of the Balfour Declaration.

This mandate system, however, was far from clear-cut, leaving much room for negotiation and interpretation.

The British mandate over Palestine, while supposedly endorsing the creation of a “national home” for the Jewish people, did not explicitly define the legal parameters of this concept.

This ambiguity ultimately contributed to decades of conflict and tension between Jewish and Arab populations.

The post-war era saw a significant increase in Jewish immigration to Palestine, fueled by the hope of creating a Jewish homeland and exacerbated by the widespread anti-Semitism that emerged in Europe following the war.

The waves of immigration, however, increased tensions with the existing Arab population, many of whom felt betrayed by the British and resented the growing Jewish presence.

The post-war period laid the groundwork for the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as the conflicting claims to land and identity, underscored by the ambiguous promises made during wartime, came to a head.

The aftermath of World War I also brought to light the inherent contradictions and ambiguities within the Zionist movement itself.

Different Zionist factions held vastly differing visions for the future of Palestine, ranging from a fully independent Jewish state to a more autonomous region within a larger framework.

The war, and its impact on the region, further heightened these internal divisions, as different groups vied for influence and resources.

The war also highlighted the challenges of reconciling competing national claims, setting the stage for the prolonged struggle that would define the relationship between Jews and Arabs in Palestine for decades to come.

World War I’s impact on the Zionist movement cannot be overstated.

The war served as a catalyst, accelerating the momentum of the Zionist project while simultaneously exposing the inherent complexities and contradictions of the movement’s goals.

The wartime alliances forged, the geopolitical shifts that transpired, and the ensuing wave of immigration fundamentally transformed the Zionist landscape, creating both the opportunity and the challenge of establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine – a project that would continue to shape the Middle East for generations to come.

The promises made amidst the chaos of war, however, would come back to haunt the region, laying the groundwork for the decades-long conflict that has defined the region ever since.

The legacy of this war is not merely one of shifting political boundaries and the rise of new national aspirations, but of a complex and often tragically intertwined history that continues to impact the modern world.

The ambiguities of the Balfour Declaration, coupled with the complexities of the mandate system, laid the fertile ground for misunderstanding, mistrust, and conflict, a legacy that continues to resonate in the twenty-first century.

CONTINUE

Chapter 2: The Interwar Period: Growth, Conflict, and the Rise of Revisionism – Library of Rickandria

In the Land of Zion – Library of Rickandria

Chapter 1: The Genesis of Zionism: Early Ideologies and Influences

Chapter 1: The Genesis of Zionism: Early Ideologies and Influences – Library of Rickandria